Michael Joseph’s first visit to Provincetown left him underwhelmed. “I don’t understand it,” he thought. “Why do people love this town?”

The photographer made the requisite stroll down Commercial Street 15 years ago, perusing galleries, eating a lobster roll, taking a few photos — of buildings, he thinks, and in the graveyard; he doesn’t really remember, he says — then catching the ferry back home to Boston.

Later, he complained to a friend, who pointed out his mistake: “You treated it like you’re a tourist. You didn’t treat it like you belong there.”

A few years later, Joseph returned to Provincetown and stayed with friends for a week. He navigated the crowds at Spiritus and spent late nights at the A-House, learning, he says, about gay culture from peers. “The world was flipped upside-down,” he says. “I didn’t have to self-regulate. I didn’t have to worry.”

That week, Joseph stopped by the old Provincetown Bookshop, the one that’s now a cannabis shop, and discovered Norman Mailer’s Provincetown: The Wild West of the East, a book of evocations named for the words Mailer used to describe Provincetown to Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961. As the story goes, at least according to the book’s editor, J. Michael Lennon, Kennedy asked Mailer what Provincetown was like, and he told her, “It’s the last democratic town in America. Everybody is absolutely equal here.”

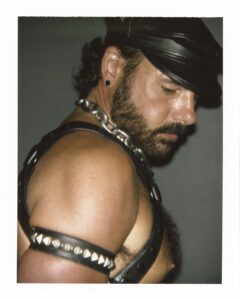

Now, more certain that he belongs here, and more certain of his subjects, Joseph walks down Commercial Street with his vintage Polaroid camera in hand, going up to strangers who look intriguing and asking if he can take their portraits then and there for his own project with the same title as the Mailer book. Joseph’s Wild West of the East is an attempt to document in photographs the subversive, egalitarian spirit of Provincetown that Mailer celebrated.

It’s an identity some say is fading away. But Joseph still sees it. “Everyone claims that Provincetown isn’t as artistic or as bohemian as it used to be,” he says. “I’m kind of over the complaints.”

His portraits, taken on a 1971 Polaroid Big Shot — the same camera Andy Warhol used for his iconic silkscreen portraits — are portals to a Provincetown where eccentricity thrived.

Joseph’s framing is intimate and playful. Most of his subjects are seen from the chest up — or chest down. He gets close and wants us to notice the details. His project, he says, is “really just about face and expression.” The subdued colors of instant film give his subjects a timeless aura. But it’s the personalities of the subjects themselves — the resplendent queens, scantily-clad bears, and gentle-eyed wanderers and artists, not daytrippers — that bring a different time to mind.

In an age where subcultures are often reduced to aesthetic trends created for TikTok or Instagram, Joseph, with his eye for true outcasts, captures the remnants of subcultures that haven’t been, and maybe can’t be, reduced to “likes.”

Before beginning Wild West of the East in 2018, Joseph was photographing America’s so-called travelers, people he describes as “lost youth who abandon home to travel around the country by hitchhiking and freight train hopping.” These young people are the subject of Joseph’s new book, Lost and Found.

Tattoos on young yet weathered faces, disheveled hair, torn up clothes, piercings, bandanas –– travelers have their own hard but earnest looks captured, in this case, in black and white with Joseph’s digital camera. The up-close portraits, taken on streets in cities across the country using only natural light, are free from distracting background scenes and focus on the intensity of his subjects’ gazes and the pride with which they wear their road-weary experiences.

Thinking back to what prompted him to begin this series in the first place, Joseph says he wanted to meet these people because they were unlike him. “At a certain point, your friends circle closes, your family circle closes, and you’re not going to meet these people because they just don’t run in your circles,” he says.

On a trip to Las Vegas with friends in 2011, Joseph saw a lanky, sunburnt, blue-eyed, blond-haired man on the side of the road. He introduced himself and took some photos without learning the man’s name or story.

Three years later, Joseph ran into the same man by chance at a Chicago train station. Knuckles — this time Joseph learned his name and something of his life — introduced him to his fellow nomadic friends. That was the beginning of Joseph’s project documenting travelers’ lives. He didn’t plan it, he says; “it just happened by talking.”

As Joseph crisscrossed the country creating what became Lost and Found, many of his subjects lost their lives to overdoses and accidents. “I was going to one memorial after another in New Orleans,” he says. He met their families and began to understand the suffering that comes with the estrangement many travelers experience.

The project was heavy, he says, and he needed a counterpoint. “I really wanted to do something that was very light and colorful and not black and white.”

He starting thinking about the photographs that would ultimately become Wild West of the East. “I’m in Provincetown all the time,” he remembers thinking — it doesn’t take long for him to get here from his home in Boston’s South End. “Why not commit to doing something here?”

One thought gave him pause, however. “I was a little bit worried that it might ruin the town for me,” he says. He thought it might be “kind of like the Wizard of Oz when you see what’s behind the curtain.”

That hasn’t happened. This summer will be Joseph’s seventh working on portraits for the project. He knows that walking down Commercial Street, camera in hand, he is going to meet new strangers, each with a certain flair.

American Wanderlust

The event: Lost & Found: Michael Joseph artist talk

The time: Saturday, May 18, 3 p.m.

The place: Twenty Summers Annex, 494 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free; $20 suggested donation