At one time, before they ripped up the rails in northwest Wellfleet, I might have hopped on a red caboose to visit Otis. I had this thought as Otis and I sat on a bench waiting for the Amtrak train in Lamy, New Mexico. I was sad to leave him after my visit, but honestly, I was also excited to climb aboard and into my little private room. I know Otis would get this. He’s a dog.

My visit with Otis out here in this wild openness was revelatory, making me realize one thing about myself: if you give me a home where the buffalo roam, well, I’ll get very nervous. Something about this expanse unsettles me. Maybe that’s why the Ancestral Puebloans moved from the mesas into alcoves on the sides of cliffs. But I’m getting way ahead of myself. Let me get back to Otis.

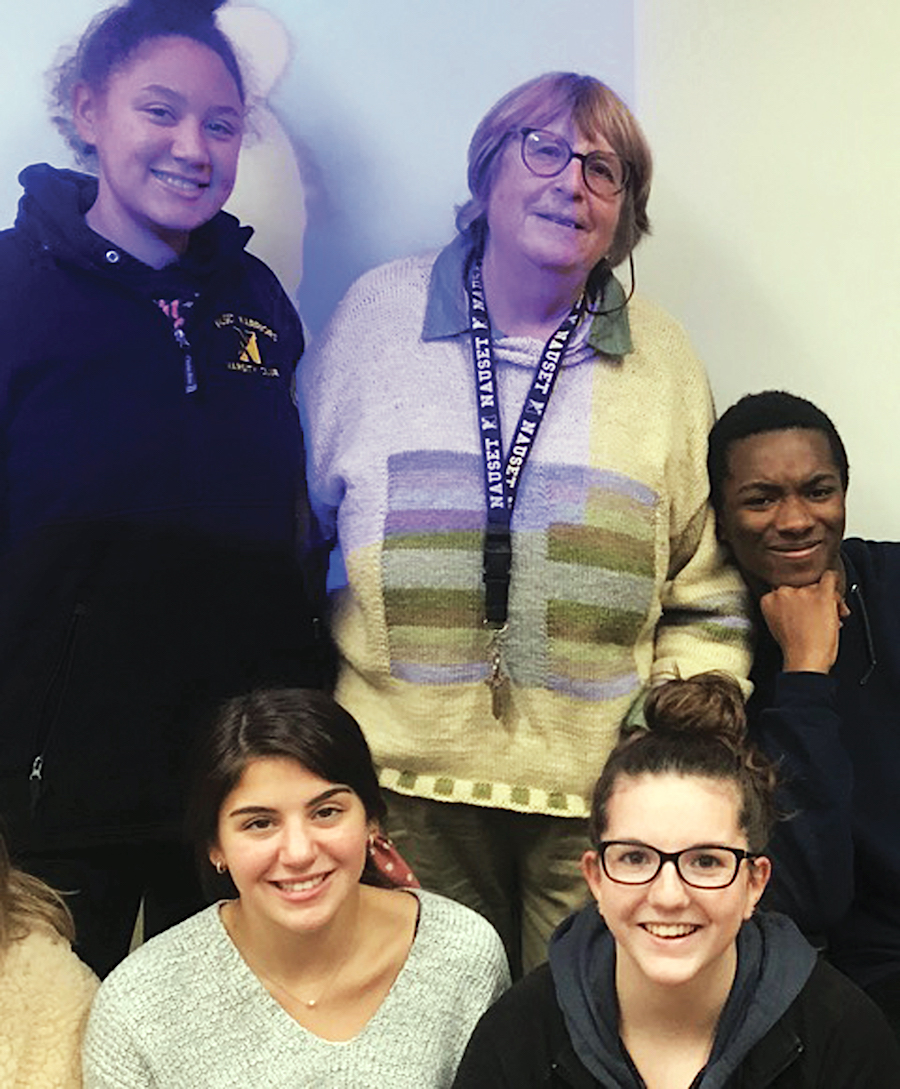

In the summer, I often see Lisa Brown around town in her red truck with Otis riding shotgun. I’ve known Lisa since long before Otis appeared on the scene. A couple of years ago, after she retired from teaching at Nauset High School, Lisa and her wife, Deirdre Oringer, built a little adobe house in the high, empty New Mexico desert.

“You want to dog-sit for Otis next winter?” Lisa asked through her truck window one day. “Our place out near Santa Fe is all yours for a few weeks in February if you’ll hang with Otis while we’re gone.” Otis gave me an encouraging look.

Done deal. My wife, Kristen, and I were both on board, but I planned to go out there a few days before Deirdre and Lisa left, to bond with Otis. He’s quirky. Maybe I am, too. The thought of airline seats and airports put me off. It was Kristen who reminded me that I’d always wanted to take a cross-country train.

Otis would have loved my roomette, the sleeper on the Lake Shore Limited. The train leaves Boston in the early afternoon and arrives at Union Station in Chicago the next morning. This stretch hugs small rivers, parallels the Erie Canal, and is a warmup for what’s to come. There is the classic locomotive woo-wooing as the train crosses intersections, the dining car, the folding down of the bunk by the porters, the gentle rocking and rolling during the night.

The sun goes down somewhere around Albany and rises somewhere around Toledo. In northern Illinois, the landscape opens, hints at agriculture, then soon is swallowed by Chicago.

I’m on the Southwest Chief when it rolls out of Union Station that same afternoon. Field and farmland open up again, and the Chief rolls past farmhouses that glow in the afternoon light. I have the salmon for dinner. I listen to jazz while they switch locomotives that night in Kansas City.

The sunrise in eastern Colorado lights up the vastness of the semi-arid high desert. In the observation car there is more window than wall. The prairie and sky wrap around me. I smell coffee. There’s an announcement: “The dining car is now open for breakfast.”

The Chief is late arriving in Lamy, population: 186, but by now, time has become irrelevant. The isolated station looks like a Western movie set where a gunfight might erupt momentarily. There are tumbleweeds; a cold, high-altitude wind; a trace of snow. Lisa and Otis are waiting on the otherwise empty platform.

The red truck sports a turquoise New Mexico plate. Lisa keeps the old Massachusetts plate on the front. To show further loyalty to her hometown, the tailgate is plastered with stickers to the general tune of “Eat More Oysters.”

Lisa and Deirdre’s desert outpost is about 30 miles south of Santa Fe. The landscape here is ocean-like in its vastness, a spread of scrub juniper and pinyons on a canvas of rust-colored soil. We are surrounded by mountains that are dusted with snow. I am soon breathless. Lamy sits at 7,500 feet.

“We’re in the middle the Galisteo Basin,” says Lisa, ever the teacher, adding more geographic details. The house is on high ground, and looking out from here you feel like you are floating on a wave. You can see their neighbors, which doesn’t mean they’re next door. Their houses look like ships, off in the far distance.

The Galisteo Basin is a mind-shifting stretch of adobe-colored earth. It covers almost 500,000 acres and has been the home of Pueblo peoples for some 1,000 years. The mountains that surround us, the Sangre de Cristos, the Sandias, and the Ortiz, make it clear that this was also once New Spain. The road we’re on is called Camino de los Abuelos.

The following day, we head up Los Cerrillos Road into Santa Fe. Snow blows horizontally through the main plaza, and folks pull down on their cowboy hats. Santa Fe strikes me as a “dress-up” town, and that’s confirmed by folks who live there. “I like to be seen,” one of them tells me. I’d venture to guess there is a low percentage of cowboys under those hats.

Turquoise, silver, and native woven coats are slung over shoulders all over town. Every street seems a runway. Jewelry glistens and sparkles behind plate glass windows. Native men and women sit outside, bundled up, their own jewelry and pottery displayed on blankets on the sidewalk bordering the main plaza, a sight that puts me in an editorial frame of mind. I find myself sitting atop my own high horse.

After Deirdre and Lisa hit the road, it’s just me and Otis, and he is warming up to me. Without hesitation he climbs into the red truck, and we drive back to Lamy to greet Kristen as she steps off the train. For the next 10 days the three of us explore the magical surroundings of Santa Fe.

The La Cieneguilla Petroglyphs are just outside the town. A bare gravel parking lot and minimal signage make it feel like a treasure hunt. It takes us a bit to locate the rugged trail, which is clogged with tumbleweed. Suddenly, magically, dozens and dozens of petroglyphs appear on the basalt rock faces. They were carved by Puebloan people between the 13th and 17th centuries. We stand there and imagine the sounds, the hands, the tools, the minds.

A drive farther north takes us to Abiquiu, where witch trials were held between 1756 and 1766. Reading historians Malcolm Ebright and Rick Hendricks’s The Witches of Abiquiu suggests that the Puritans of Salem had nothing on the Franciscans of New Mexico. It was also amid the rock formations and light of Ghost Ranch in Abiquiu that Georgia O’Keeffe lived and painted. The ranch, but not the artist’s house, is open to the public.

We trek miles of dusty ochre trails in the Galisteo Basin Preserve. The next day, we leave Otis at home while we check out the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe with its extraordinary collection of some 150,000 artifacts from more than 150 nations. Next door, we visit the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. In a restaurant attached to a feed store, we learn how to answer the ubiquitous Mexican restaurant chile sauce question: “Red, green, or Christmas?” Answer: “Christmas.”

Just as this place has almost overwhelmed me, as if he understands, Otis climbs into my lap. All 70 pounds of him. A heavy comfort, I must admit. The next day, Deirdre and Lisa return, and Otis ditches me. But we remain friends.

We roll slowly away from the station in Lamy, and the Chief woo-wooing through Raton, Kansas City, Topeka, and Naperville is a slightly familiar movie running backward. We dine with Brian Yoder, an Amish cabinetmaker, sit sun-soaked in the observation car, and marvel at an America that slowly closes in on us west to east: vast prairie into fenceless farms, into broken fields, into back yards with their cars and grills, and brick mill buildings along cold riversides.

And now, once again, we’re down the tracks from Otis, at least when he’s back for the summer.