When Bernhard Dessecker and his partner, Della Spring, were getting duct work done for air conditioning at their house in Wellfleet, the excavators dug up a trove of silver objects, including trophies, bowls, and silverware. Dessecker, a designer of light fixtures, set to work polishing and restoring the objects — and soon had an idea for how to use them.

The result, Wellfleet Silverado, a chandelier he designed and constructed, is now hanging at the Jeff Soderbergh Gallery in Wellfleet. The fixture shimmers with reflected light gleaming off the highly polished silver objects, which cascade downward, appearing to be caught mid-air while tumbling to the ground.

This playful subversion of gravity and the surprising placement of lights inside bowls or coming out of saucers, convey a sense of magic, underscored by the mystery of the objects themselves. Dessecker has no idea why the objects were buried in his yard or to whom they once belonged. Some of the trophies were from dog shows. There’s an engraved silver box, which he used to hide an electronic device to run the LEDs. One item is inscribed “1964.”

Dessecker’s use of found objects is a core component of his working method, a strategy that allows him to both invent and conjure associations. In an earlier piece, Dessecker, a native of Germany, created a chandelier from headlight components of BMWs. The project began as a collaboration between the automobile company and the National Bavarian Museum in Munich. The result, 85 Iconic Eyes, was an elegant egg-shaped chandelier that was eventually serially produced by the Dutch design firm Moooi.

Earlier in his career, Dessecker worked as a member of the design team at Ingo Maurer before pursuing a freelance career as a designer and lighting consultant, working on jobs ranging from large municipal projects to smaller custom designs.

Dessecker first came to Wellfleet in 2015 at the encouragement of Spring, who is rooted here. He goes back and forth between Wellfleet and Berlin, and while in Wellfleet he works out of a studio in his garage.

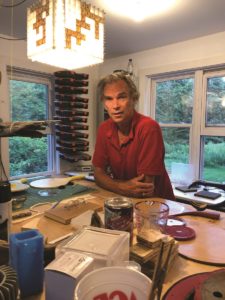

“A lot of the design world is very serious,” Dessecker says. A quick look around his studio proves he is hard at work to change that. He stands at a workbench covered with parts of past and future projects, including driftwood and a section of a gutter. There is a pair of Kadema paddles, which he has combined with coffee can lids to create a beachy lamp. Above the table hangs a lamp made from an aluminum grid and Scrabble pieces. There are flies in resin for one project and molds of oversized kitschy crystals with which he is thinking of making another chandelier.

In Dessecker’s workshop, projects often “come to life through accidents,” he says. Recently, he dropped a lightbulb. The glass broke but the internal LED structure remained. He is now experimenting with casting a bulb in resin, which presents a new technical challenge. That’s something Dessecker enjoys. “Technical challenges always bring me further to something else,” he says.

Dessecker’s studio is outfitted with well-organized tools, a lathe, and a milling machine. There he works out problems of fabrication and electricity.

Working with gold leaf is one challenge he’s mastered. In Fire My Light he combined it with a charred log he found at Newcomb Hollow Beach for a dramatic contrast of surfaces and color. A rod extends from the log holding a Lego-adorned light.

This piece is representative of Dessecker’s inclination to mix high and low culture and luxury with the commonplace. In addition to the gleaming chandelier of silver at the Soderbergh Gallery, Dessecker is represented by a lamp made from an upturned cooler bag punched through with a smiley face.

“I wanted to do something spontaneous,” he says. “Something that makes people laugh and smile. I like to make people happy. Lighting is a good tool for that.”