In The Upper Hand, a recent painting by Les Seifer, a lion prowls near a kneeling man who is preparing to shoot a rifle. The man, however, is not aiming at the lion. His back is turned to it; he’s focused on some other target beyond the edge of the composition.

Seifer, who lives in Brooklyn, describes his painting process as picture making. He arranges a variety of elements — including cut-out figures, scrap paper, and paint — in relationship with each other to build open-ended narratives. Lately, he’s been painting figures and animals using heavily diluted liquid acrylics on rice paper or other absorbent, delicate Japanese papers. The papers, full of figures and animals, usually pile up before he cuts out the characters and starts composing his pictures.

The lion and hunter in The Upper Hand were pasted onto a wood panel painted gray, with a grid of faint red lines. The placement of the figures suggests the narrative. “I like an air of mystery,” Seifer says. Is the lion hunting the hunter? Who will prevail? Seifer might have his own thoughts about this story, but he’s just as happy for viewers to imagine their own. “I like when other people see something completely different,” says Seifer. “It’s just as valid.”

In most of his paintings, the relationship between the characters seems conflicted. In Passing, Passed, a man whips a horse; in This Thing’s Getting Away From Us, a tiger and a man in 19th-century garb lunge at each other. Seifer’s current exhibition at the Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown, which will be up through Sept. 10, also includes work from earlier series of paintings, one focused on cowboys and the other on the Revolutionary War.

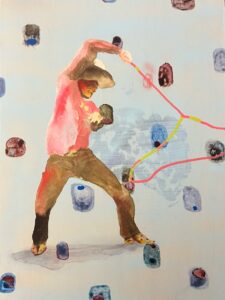

In Wrangling the Rain, a cowboy twirls a lasso. It’s an archetypal image of American masculinity, but Seifer brings a playful touch to the image. Fingerprint-size raindrops create a loose grid in the background, and splashes of bright pink move between the cowboy’s shirt and lasso.

“About 10 years ago, I started painting cowboys out of the blue,” says Seifer. He continued painting them for four or five years. “I have a very ambivalent relationship to cowboys,” he admits. As a child growing up in Yonkers, N.Y. in the 1970s, Seifer, like many boys of that era, played with toy guns, drew Army figures, and often enacted imaginary battles between cowboys and Indians.

He’s still intrigued by the mythology of cowboys. “There’s an independence to them, which I really love,” says Seifer. “They’re uniquely American.” But his view has grown critical. “There’s a flip side to the image of the cowboy,” he says, citing the takeover of land, toxic masculinity, and gun culture.

In his series of paintings about the American Revolution, he continued exploring themes of independence and violence in American history. “America is a country founded on violent revolution,” he says. “It’s continued to be violently revolutionary ever since, for better or for worse.” A Brawl in Harvard Yard depicts a fist fight among a group of men wearing waistcoats, breeches, and tricorn hats. Cascading ribbons of color look like drips of blood and like party streamers in an image that captures Seifer’s simultaneously playful and critical stance.

Seifer hearkens back to his childhood not only in his subjects but also in his free, intuitive way of painting. In adolescence, he resolved to draw as realistically as possible. He meticulously painted copies of album covers on the backs of denim jackets when he was in high school. Then he studied illustration at Syracuse University. Now, Seifer says he’s trying to get back to the attitude of a kid playing around with materials. As a consequence, it’s not only the people in his paintings that seem to be caught in a battle. The way he paints is fraught with tension between abstraction and representation.

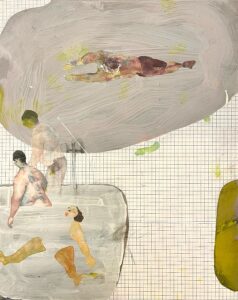

The two men in Storm Coming and the figures in The Bathers reveal Seifer’s command of drawing the human figure, but he escapes any demands of representation in the abstract backgrounds of these compositions. In The Bathers, he lays down gridded paper that his son, an engineering student, uses for his homework. In Storm Coming, a washy ground of dark gray paint could be water, but it also reads as brushy, abstract mark-making. A blob-like form covered in a red and orange pattern emerges from the right side of the painting. A man stands on another abstract shape as if it were a rock. The painting is constantly teetering between abstraction and reality. The men hold thin ropes, like lassos, which seem to harness the tension in the painting and maybe the oncoming storm, too.

“This painting feels really Cape Cod,” says Seifer about Storm Coming. He has been coming to his family’s house in Orleans since he was a child, and he has shown work in Provincetown since 2001. Before exhibiting at Rice Polak, he showed with Ernden Fine Art Gallery and Boathouse Gallery, both now closed. Yet landscapes don’t usually figure into his paintings. Rather, his isolated figures on abstract grounds are typically removed from their original environment to suggest a landscape that’s more internal.

“These are usually personal allegories,” says Seifer. The cowboy series started at a time when he was trying to assert some independence from his day job in advertising technology. There’s still conflict in much of his recent work, but there also seems to be some yearning for moments of ease. A few images from the past year are of swimmers and bathers. There’s a sense of freedom in the images, he says.

In Staring at the Starlings, two men wade into an aqua, oval-shaped body of water. Above them, in a sky made from graph paper, erratic blue and black marks occupy the left-hand corner of the composition. The marks look like abstract gestures, but Seifer identifies them as a horde of starlings flying by.

Like the men about to dive into the water, the birds convey a feeling of escape. “The world is a weird, chaotic, scary place these days,” says Seifer. “It gives me a lot of anxiety. These scenes tend to be of people coping in whatever way they can.”

Personal Allegories

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Les Seifer

The time: Aug. 28 to Sept. 10; opening reception, Friday, Aug. 29, 7 p.m.

The place: Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free