Most cultural histories of Cape Cod begin with Charles Hawthorne’s establishment of an art school in Provincetown in 1899. But Lee Roscoe knows the story is much older than that.

In her new book, Wampanoag Art for the Ages: Traditional and Transitional, Roscoe features work by and interviews with Native artists working in traditions that span thousands of years.

“I’ve always admired the creativity, freedom, and immediacy of Indigenous life,” says Roscoe, who lives in Brewster and whose background includes environmental education and activism. “There’s joy in living directly with the Earth — not just fishing and clamming, but things like using deerskin for clothing and clay from the ground to make vessels. The Wampanoag embody that way of life in their art.”

Roscoe’s book covers eight different but interrelated forms of Native art, from the construction of wetu, or dwellings, to contemporary paintings and mixed-media pieces incorporating traditional designs and materials. What they all have in common, Roscoe says, is how physical objects incorporate aspects of the spiritual and divine as intrinsic to the process of creation.

“For the Wampanoag, there’s no separation between art and life,” she says. “There’s always a combination of the spiritual with the material. Everything that was created has an element of the sacred in it. So there’s a balance in everything that’s created.”

Reciprocity is an integral part of that balance. “As Wampanoag elders will tell you, there is always reciprocity between what you are taking and what you are giving back,” says Roscoe. For example, tobacco is offered to the Earth when cedar saplings are taken from the ground for use in the construction of wetu.

Roscoe describes the book, which began as part of her research for the Plymouth 400 project, as a “true labor of love” that took more than four years to complete.

“From long years of activism and journalism — and reading about and listening to Wampanoag elders while researching a book about Monomoy — I realized it would be wonderful to look at the Wampanoag lifeway through their arts,” she says. “It’s a way of honoring them and revealing things about their long history and deep culture that many people aren’t aware of.”

Roscoe’s activism for Native land reclamation (she worked on a successful effort to preserve 287 acres with Native archeological significance in Mashpee in 2002) helped her win trust and get access to sources. “I got to know many members of the tribe, especially Chief Earl Mills,” she says. “It was the people who told me about their art and gave me all the information for the book.”

Roscoe says she didn’t want to tell the story of Wampanoag art from her own perspective. “None of this is me,” she says. “I didn’t come to this as an art historian. I wanted the artists to tell me what they do and how they do it — and their rationale for doing so.”

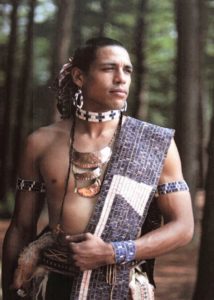

Accordingly, Wampanoag Art for the Ages is full of the voices of artists working to maintain the continuity of their long cultural tradition. Mashpee Wampanoag, Pequot, and Narragansett artist, teacher, and actor Annawon Weeden describes the process of creating a wetu as a form of creative expression: “No discredit to the artists out there and the media they use, but I hate making something which will just hang on a wall,” he says. “I like to make useful things. I consider a house, building a home, art.”

Master mat-maker and twiner Julia Marden, who is an Aquinnah Wampanoag from Falmouth, describes the labor-intensive techniques involved in making traditional mats from cattails and bulrushes — natural materials that are increasingly imperiled by pollution (cattails in particular need clean water in which to grow) and invasive species of nonnative grasses. Tribal elder Ramona Peters (Nosapoket) explains how Wampanoag pottery — which has been used for storing materials as varied as food, pigments, and human ashes — can express “a symbolic representation of the way we were, and the way we are” through its shape and markings. For example, a four-cornered design motif on the mouth of a vessel can represent “men going out in four directions to bring back food and knowledge to add to the pot.”

And marine biologist and artist Elizabeth James Perry, an Aquinnah Wampanoag, delves into the intricately layered aspects of the art of wampum — colored shells that are used as currency, for adornment, and as a means of record keeping — while emphasizing its sacred and private nature. “It is an ancient tradition with a lot of complexity to it,” says Perry. “There’s a lot of specialized knowledge which is not publicly shared.”

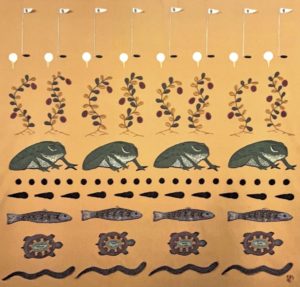

Roscoe also engages with other Wampanoag artists’ work in ways that are closer to Western forms of expression while still using tribal traditions to inform their art. Self-taught artist Robert Peters’s acrylic on canvas paintings incorporate Wampanoag stories, practices, and symbolism. Emma Jo Mills Brennan’s fabric and mixed-media piece One Sustains Us, One Does Not (now in the collection of the Mashpee Wampanoag Museum) tells the story of how an entire ecosystem of Native land was irrevocably lost when it was filled with gravel, covered over, and made into a golf course.

Peters’s and Brennan’s works are well described by the subtitle of Roscoe’s book — “Traditional and Transitional” — which also sums up what she believes contemporary Wampanoag art is all about.

“Wampanoag artisans always express gratitude to their ancestors in their art,” she says. “But they also stress that they are working in the present — and that their arts are also heading for the future. They take a little from both worlds. And they’re still here.”

Lee Roscoe will discuss Wampanoag Art for the Ages at the Eastham Public Library on Tuesday, Nov. 22, 6 p.m. See easthamlibrary.org for more information.