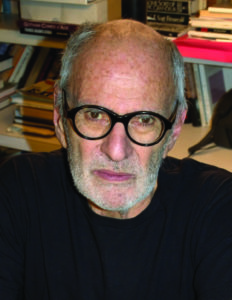

To understand why Larry Kramer was a great artist and a singularly influential activist, you have to examine how much the world has changed from plague to plague, HIV to Covid-19.

In 1983, when Kramer wrote his essay “1,112 and Counting” in the gay newsweekly New York Native, the title referring to the number of gay men in the prime of life who had suddenly succumbed to a mysterious syndrome of rare diseases, there was no internet or social media. Gay people had achieved some freedoms, but they were limited to urban enclaves, and many, if not most, remained in the closet. The Stonewall Riots had occurred only 14 years earlier, and the law and judgment of society had changed little. Lesbians and people of color were often excluded, and bisexuals, drag queens, and trans people were sidelined and often scorned. The aspirational look among gay men was the “clone” — mustachioed, masculine, and muscular.

Kramer was an Oscar-nominated screenwriter (for adapting Women in Love), and had written the satirical and farcical novel Faggots, about the privileged world of the beach retreat Fire Island Pines, where successful gay men enjoyed promiscuous sex and wondered why they were unhappy. He was not especially famous.

Facing an exploding epidemic, Kramer called for gay men to stop having sex — not a popular message. People were dying — mostly gay men, junkies, Haitians, and hemophiliacs, i.e., people whom the government and the greater public didn’t much care about.

In 1983, HIV and AIDS were in the process of being identified, and this novel retrovirus was finally understood to be blood-borne, transmitted sexually through semen and via needle exchanges and blood transfusions. It was otherwise not especially contagious but almost always fatal.

Kramer helped establish Gay Men’s Health Crisis, but his stridency and polemics eventually got him kicked out. He wrote a play about this, The Normal Heart, which opened in April 1985 at the Public Theater, off-Broadway, starring Brad Davis, then a movie star, as Ned Weeks, a Kramer stand-in.

I went to see the play at that time with my lover (now husband). It was electrifying. The walls were covered with the names of the dead. The love story between Ned and a New York Times reporter who gets infected was poignant and tragic. The second act featured impassioned speeches by all the main characters, about their powerlessness to stop people from dying horrific deaths. The mayor of New York, Ed Koch, was accused of being a closet case, and both the city and Reagan administration in Washington were deflecting the crisis as much as they could. Reagan never spoke of it. These leaders are accused in the play of being murderers through their deliberate negligence.

For me, what was most brilliant about the play, and the reason it holds up (though it’s no longer quite as electrifying), is Kramer’s perceptions of himself and his friends: he is transparent about his own moral rigidity, and sensitively conveys how difficult it was for his powerful friends, who fought long and principled battles for sexual freedom, to give it up in order to save themselves. The immature protagonist of Faggots has grown up in the persona of Ned Weeks: it’s love, not just sexual fulfillment, that matters to him.

Frustrated with GMHC’s political neutrality, Kramer went on to form ACT UP: AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power. He became more and more strident and polemical as the epidemic grew more catastrophic. He alienated many, but ACT UP’s forceful and confrontational tactics changed the political landscape and have been a model for other groups to this day. His refusal to be ignored, and his demand for AIDS to be treated as a national emergency, were essential catalysts for a new generation of LGBT activists.

Kramer’s follow-up play to The Normal Heart in 1992, The Destiny of Me, starred John Cameron Mitchell as Ned Weeks and had at its center a fictionalized meeting of minds between Weeks and his doctor, based on Anthony Fauci, now the public face of Covid-19. The Destiny of Me was a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

Kramer himself fought HIV valiantly, lived on the brink of death, was saved by a liver transplant, and kept writing and publishing. He died on May 27 at age 84, a true survivor. Despite all his flaws, the LGBT community owes him an enormous debt. We were lucky to have him.