Michael W. Twitty’s Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew comes to a boil slowly. For readers interested in the intersection of identity, food, and cooking, it’s worth watching the bubbles come to the surface.

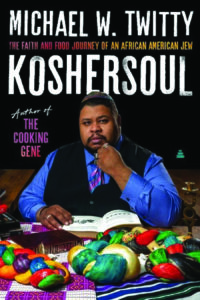

Twitty is a Black culinary historian and memoirist. His first book, The Cooking Gene: A Journey through African American Culinary History in the Old South, published in 2017, won a James Beard Foundation award. In Koshersoul, Twitty writes about his conversion to Judaism and his exploration and imagination of “the cuisine of the chocolate chosen.”

Twitty devotes much of Koshersoul to mayseh — Yiddish for “short tales.” He layers his somewhat random mayseh with accounts of too many disappointing encounters with racism and rejection among his new tribe: on Maryland buses, in a mentor’s kitchen, at a religious school where he served as a stellar teacher.

The layers are filled with intense conversations he has had with a wide array of Black Jews and, eventually, anecdotes that demonstrate his growing confidence. With patience, readers will appreciate why respect for diversity (and not just a tolerance of it) needs to matter in and out of shul.

Twitty sets his table by explaining how his identities throughout his life have made him, as he writes, “out of line of what normative is supposed to be.” He was marginalized in America as a young Black man. He was teased and shamed within Black culture for his effeminacy and queerness. He was fat in a country that prizes being thin. He was marked as peculiar at school because of social awkwardness and a passion for books and learning.

A self-described “proud autodidact,” Twitty writes that Judaism appealed to him because it emphasizes learning and wrestling with text. “Part of the reason I transplanted into Judaism,” he writes, “was because I really liked that I could be that part of myself, and have it be both a sacred and secular experience.”

But Twitty’s identification with core tenets of Judaism wasn’t enough to create a seamless adaptation to orthodoxy. He came to understand that wherever he and other Jews of color exist, they hear and see that they don’t belong. They are endlessly and variously asked, Why are you here?

Twitty doesn’t want to be asked why he and other dark-skinned Jews attend Shabbat services or keep kosher. He needs Jews of European descent to acknowledge Jews of color — Sephardi, Mizrahi, and Black converts — as fellow travelers. Twitty feels most seen and heard when an Ashkenazi Jew greets him without question as chaver: Hebrew for “friend.”

Twitty’s frustration spills over when he thinks of the many ways dark-skinned Jews have been historically marginalized. “Our story isn’t endnotes and footnotes,” he writes. “It’s whole burned chapters that have been left out of the Jewish, African, Middle Eastern, western, American, and Atlantic history books, a history that dares anyone to imagine us as an exotic novelty.”

Twitty neutralizes this supposed exoticism by diving into food and cooking. He recovers and imagines the nexus between kosher and Southern Black foodways. Though it might seem like a leap, he’s laid the groundwork for readers to care about ingredients such as black-eyed peas and cornmeal. Whether or not readers are Jewish, they will likely want to know more.

In addition to being a gifted writer and insightful thinker, Twitty is a wildly imaginative cook. The foods he describes, and the recipes he includes, borrow ingredients from across a diaspora that spans from Africa to the American South.

One particularly brilliant example envisions an Afrocentric Passover seder plate of foods symbolic to the biblical story of Exodus. He substitutes hot pepper for horseradish as a way to include the American South in a Jewish history of enslavement. And he suggests molasses and pecans as ingredients for charoset, which symbolizes the mortar and brick that Jews made in Egypt for the pharaoh. These are ingredients “representing the sugarcane that fueled the beginnings of slavery and the duality of our culture in exile.”

In these substitutions and creative interpretations, Twitty makes good on his assertion that “no recipe comes without hurt in this world, or deep pleasure or even excess.” Through his cultural and culinary journeys, he realizes his goal of developing “a culinary voice that could speak to those parts of who I am.”

In Koshersoul, Twitty explains how he eventually found his essential soul — and soul food — as an observant Jew who keeps the dietary laws of kashrut. He braids these influences and histories into a most extraordinary challah of a book.