Summer unfurls to reveal the Cape Cod most people imagine: sandy, sticky, hedonistic, salty. There’s a looseness to the air. Right now, the lush chestnut tree outside the window is making all kinds of big, soft noise in a southwest breeze while steady traffic hisses down the street. It seems like all the friends from all the places have chosen the same week to arrive, and it feels like forever since I’ve seen winter friends, who are in the scrum of it themselves.

“See you in the fall!” we holler to each other, waving as we leave the post office or grocery store. Off work, we go on “insta-cations,” taking ourselves to the beach, or to a hammock, drive-in, art walk, or drag show.

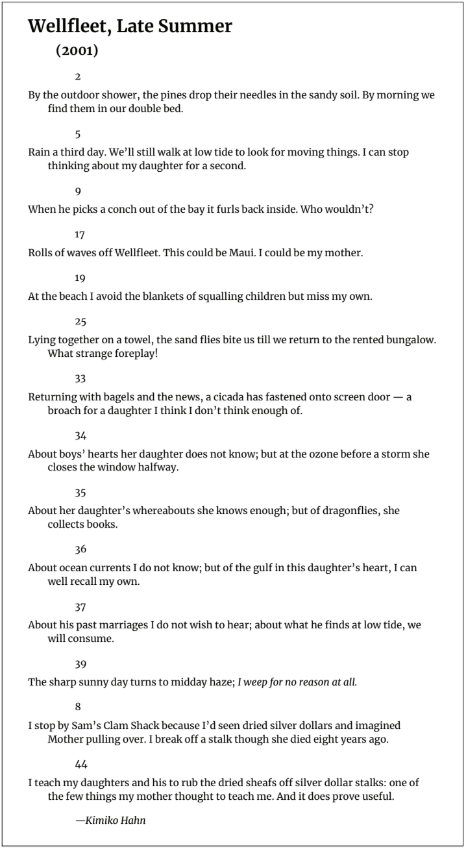

Kimiko Hahn’s poem “Wellfleet, Late Summer” might not exactly describe everyone’s Outer Cape August, but doesn’t it have the vibe? I love the way it at once skips between and holds in one breath details from summer life (tides, cicadas) and inner life (memories, worries, relationships).

To capture this swirl, Hahn has used the zuihitsu, a poetic form developed in Heian Period Japan (794–1185). Usually translated as “follow the brush,” a zuihitsu is crafted to feel spontaneous, full of strange leaps, and it embraces an aesthetics of … jumble. The quirky next to the profound, the mundane alongside the exquisite.

The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon, written around 1002, was the first and perhaps still the best-known example of classical zuihitsu. In it, an erudite attendant casts her sharp eye and wit on her life in the imperial court, delighting in scathing takedowns and biting character assessments, revealing secret liaisons and creating eclectic lists on topics like “Things That Give an Unclean Feeling.” Cumulatively, Sei’s work paints an incredibly detailed portrait of both her interior and her exterior world. I read The Pillow Book as a junior in college, and it’s stayed with me ever since.

Kimiko Hahn has kept that spirit, right down to how the poem’s numbered sections skip around and even backtrack. And the line “Lying together on a towel, the sand flies bite us till we return to the rented bungalow. What strange foreplay!” So Sei. Hilarious, wry, a bit self-mocking, racy, and also certainly true.

Same with the juxtaposition of “About his past marriages I do not wish to hear; about what he finds at low tide, we will consume.” Here, Hahn makes emotional scavengers of herself and her partner, feeding off what’s been revealed, cobbling together a new relationship out of what’s been exposed.

What really makes me want to share this poem, though, is how the complicated dynamics between mothers and daughters are refracted in it and through a vacation in Wellfleet: “About her daughter’s whereabouts she knows enough; but of dragonflies, she collects books.”

I take the “her” in this to be Hahn herself, with a mother’s desire to be aware but to also have a protective vagueness (you might not want to know too, too much); it makes so much sense to me. And the later italicized “for no reason at all” — why italics? Because it’s a quote? Because we’re supposed to know there are many, many reasons for weeping? Because Wellfleet in August is so beautiful it’s hard to imagine a reason for crying?

“I teach my daughters and his to rub the dried sheafs off silver dollar stalks: one of the few things my mother thought to teach me. And it does prove useful,” she writes. I love how, in the end, the poem honors the way playful and pleasurable acts shared from generation to generation are what bind us. And how the poem sneaks up to its seriousness. Lessons from parents in accounting, cooking, cleaning, or swimming are all fine and good. But lessons in the proper action to take when you spot a white horse in a field or how to spit watermelon seeds farther than far off a dock into the bay? Invaluable.