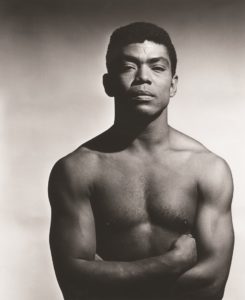

Though he was an African American born into poverty in 1931 in rural Texas, picking cotton as a young child alongside his single mother, Alvin Ailey lived a life of artistic genius as a dancer and choreographer and enjoyed phenomenal, groundbreaking success. By the 1970s, his Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Ailey School, based in New York City, was internationally recognized and beloved. It remains a beacon for emerging Black talent — talent that was largely ignored by mainstream institutions during Ailey’s lifetime.

But, as Jamila Wignot’s sensitive and astute documentary, Ailey, reveals, his rise to prominence in the dance world was accompanied by a good deal of personal torment. Ailey was gay and largely closeted, having no lasting relationships. He suffered a mental breakdown in 1980 from abuse of alcohol and cocaine and what was then called manic depression. He died of AIDS in 1989 at age 58, one year after receiving the Kennedy Center Honor for lifetime contribution to American culture.

Ailey had moved with his mother to Los Angeles in the early 1940s, and it was in California that he was attracted to dance and eventually devoted himself to it professionally. Moving to New York in the 1950s, he developed his own style of choreography, true to his African American roots, and formed his own company in 1958. Through classic, visionary works — such as Blues Suite, Revelations, and The River — and relentless touring, he built the company into a powerhouse of modern dance with a vast repertoire.

Ailey (available for streaming via watersedgecinema.org) intercuts present-day rehearsals of the company’s dancers in its gleaming new Manhattan headquarters with archival footage and gripping testimonials by Ailey’s colleague Bill T. Jones and his muse and successor Judith Jamison, among others.

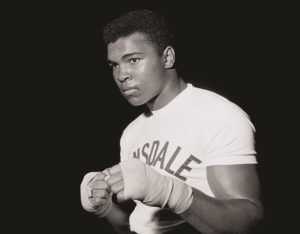

There’s an earthy dreaminess to Ailey that befits its subject. Likewise, there’s a towering seriousness to Muhammad Ali, the four-part, 7.5-hour PBS documentary portrait by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon of the heavyweight boxing champion, a treatment that he richly earned. (The series is available on demand via cable and at pbs.org.)

Though Ali, the self-declared “greatest,” is known as much as a showman and celebrity as he is for his athletic skill and accomplishments, he was also a political and inspirational hero — one who was slimed by racism even more than was his saintlier African-American forebear, Jackie Robinson.

Instead of being recognized for his brilliance, he was scorned as a fast-talking trickster. His self-awareness was seen as egotism. His embrace of the Nation of Islam and his religious refusal to serve in the military in Vietnam, were regarded as corrupt and hypocritical, not as principled and revolutionary choices for which he accepted all the personal and legal consequences. In all, the contempt he endured had more than anything to do with his being a Black success story.

Ken Burns and his team exhaustively research Ali’s life, from his Louisville, Ky., early years as Cassius Clay, through his historic and spectacular fights, to his old age and debility from Parkinson’s disease. The footage and narration (by Keith David) are dramatic and unflinching, not skipping over bad behavior — Ali’s womanizing, his dehumanizing treatment of Joe Frazier, his glib rejection of Malcolm X — but not dwelling on it, either.

Ali’s limitless and lifelong charisma comes shining through, as does his essential clarity.

Burns’s attempts to right American wrongs, particularly when it comes to race (in his series Baseball and Jazz, for example), give a sense of purpose to his work. That becomes especially clear in comparison to other well-researched historical documentaries, such as Citizen Hearst, a two-part, 220-minute special presentation of PBS’s American Experience (available on demand and streaming on pbs.org) that covers the life and legacy of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst.

It’s not that Citizen Hearst doesn’t own up to the outrageous practices Hearst either invented or perfected. They are laid out in great detail, with the onscreen participation of his heirs.

W.R., or Will, as he was known in his youth, was the only child of George Hearst, a fabulously wealthy Western mining baron. After his expulsion from Harvard, the younger Hearst became interested in the newspaper trade, eventually turning the New York Journal into the premier yellow journalism rag, besting Joseph Pulitzer at his own game and single-handedly forcing the U.S. into the Spanish-American War by falsely reporting a deadly explosion on the U.S.S. Maine as sabotage. The war was a totally unnecessary imperial escapade, but it launched Hearst into the media stratosphere.

He had no problem fabricating facts, and though he ran for office as a Democratic politician on populist platforms, he was brutally anti-union, viciously racist and xenophobic, an early supporter of Hitler, and a major proponent of putting Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II.

He bought himself a vast media conglomerate — the first of its kind — gobbling up dozens of newspapers, launching magazines, creating a Hollywood studio, and shooting and distributing newsreels. He lived with his mistress, the actress Marion Davies, and built her a castle on the Pacific in San Simeon, Calif. All of this was satirized in Orson Welles’s 1941 classic film, Citizen Kane, and, as a result, Hearst’s empire shunned the movie and helped destroy Welles’s career.

What Citizen Hearst doesn’t do, as Ken Burns certainly would, is provide viewers with a moral compass. The contemporary parallels with Murdoch and Trump are obvious and left unsaid. Instead of focusing on Hearst’s life as a nihilistic, narcissistic exercise, the documentary “balances” his destructiveness with a tribute to his risk-taking and empire-building as a businessman. And that’s, to employ current lingo, not OK.