These days, new films are difficult to track. Miranda July’s Kajillionaire, for example, premiered at Sundance in January, then opened in theaters on Sept. 25, but not locally on the Cape. It’s also available to stream, for a $20 rental fee, online. This unfamiliar journey of release is, curiously, a good match for a strange and intoxicating film.

July, a performance artist, short story writer, and writer-director of three remarkable feature films — Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), The Future (2011), and, now, Kajillionaire — has a unique and uncompromising creative voice. Her films, which are all set and shot in Los Angeles, are deliberately paced, comically surreal (some might say twee), suffused with the trappings of pop Americana, peopled with middle-class fools, and haunted by a deep well of loneliness. Her stories are moving and acted in a realistic, if quirky, style (no arch John Waters dialogue or Napoleon Dynamite deadpan delivery), and they’re redemptive in a purely aesthetic way. Art, for July, is truth.

At the center of Kajillionaire is a family of low-rent scam artists: Richard Jenkins is the conspiracy-mad kook of a dad; Debra Winger, the affectless and vaguely bitter mom; and Evan Rachel Wood, the 26-year-old quasi-autistic daughter. They live in the office of a soap factory, with walls that periodically overflow with pink foam like Old Faithful. They execute scheme after transactional scheme — robbing mailboxes, forging checks — until they meet Melanie (Gina Rodriguez), a friendly Puerto Rican who seems to like them, though it’s unclear when any of these oddballs is scamming or being honest. The movie feels like an allegory of Trump’s America, though more broadly, it’s about our 21st-century way of life. Earthquakes periodically rattle the family, which is girded for “the big one,” but the threat is nebulous and the world is oblivious. Life, in Kajillionaire, is about cash and survival and the elusiveness of love. It’s a fable that will stick in your imagination.

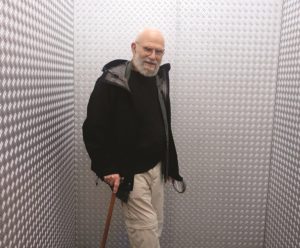

Available through Waters Edge Cinema online (provincetownfilm.org) or Zeitgeist Films is the superlative documentary Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, directed by Ric Burns, brother of Ken. Sacks, who died in 2015, was a British neurologist who spent most of his working life in the Bronx, studying the lives of those with brain injuries or diseases. He was also an extraordinarily sensitive and evocative writer, whose books and articles, from Awakenings to The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, became best-sellers and were adapted into films. He wrote, memorably, about people with neurological anomalies, such as Tourette syndrome, synesthesia, or the inability to recognize faces (which afflicted Sacks himself).

The film gives us insight to Sacks the man, doctor, and writer. He was born to orthodox Jewish scientists in London and, as a child, lived through the nightmares of World War II and his older brother’s schizophrenia. Gay and closeted, he spent most of his life running from demons, initially addicted to amphetamines, then clean and celibate for 35 years. After a lifetime of heroic empathy for his patients, he found love himself in his old age with writer-photographer Bill Hayes. Burns’s film is filled with rich testimonials by close friends, colleagues, and Sacks himself, and feels as close to autobiography as a film documentary can get.

The 2018 Broadway revival of Mart Crowley’s landmark 1968 play, The Boys in the Band, with an all-male cast that’s stellar, gay, and out, has been turned into a streamable Netflix film by Ryan Murphy, with the same cast and director, Joe Mantello. Crowley’s play, about a birthday party for acerbic Jewish Harold (Zachary Quinto) hosted by his tormented Catholic friend Michael (Jim Parsons), has been worshiped in the LGBTQ community for its humor and forthrightness, derided for its self-hatred and stereotypes, but never ever ignored. Its influence is undeniable, and despite being of its time, on the cusp of Stonewall, it has aged well, looking even more insightful and incisive in retrospect.

Mantello’s revival has much to recommend it. The performances, across the board, are worthwhile. Quinto seems to be channeling the great Leonard Frey in the original, though it works. Parsons’s amped-up Michael — a hateful and pathetic figure — takes a bit of getting used to, but he makes it his own. The Tony-nominated Robin de Jesus makes an excellent Emory, earthier as a flaming queen than Cliff Gorman was in the original, and Latinx. Andrew Rannells and Tuc Watkins are superb as the straight-ish couple with monogamy issues. Michael Benjamin Washington is terrific as the African American Bernard, and Charlie Carver nicely fleshes out Cowboy, the dim hustler hired to be Harold’s birthday present. Brian Hutchinson is effective as Michael’s friend Alan, desperate about his hetero marriage for reasons unknown. And as Michael’s slacker friend Donald, Matt Bomer is the weakest of the bunch, but his character is also the least well defined.

Mantello does a great job smoothing out the play’s contrivances, such as Michael’s vicious phone-call-of-truth parlor game, and it flows beautifully. He also “opens” things up cinematically, with flashbacks and outside sequences — it’s not needed, but doesn’t distract. Overall, the movie is an involving way to spend a couple of hours (free to Netflix subscribers), and for the uninitiated, even more so.