I step outside after dark with my dogs for an evening walk. It’s a clear night. I look up, as I always do. Where’s the moon? What phase? What else is in the sky tonight?

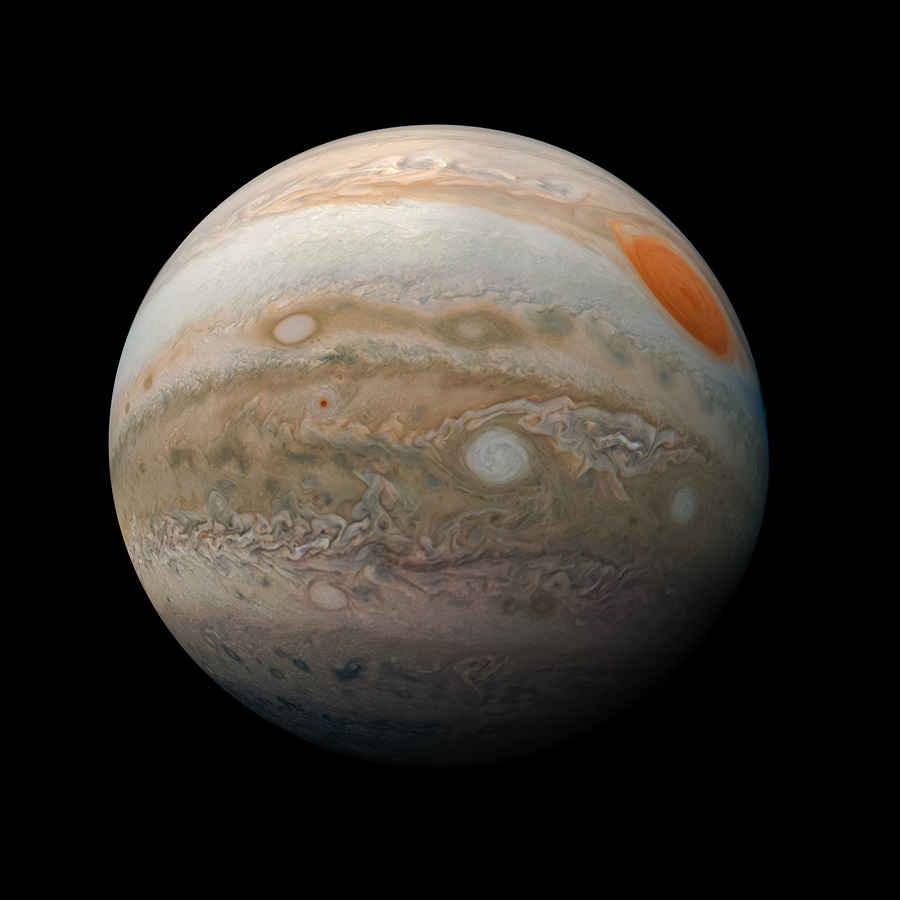

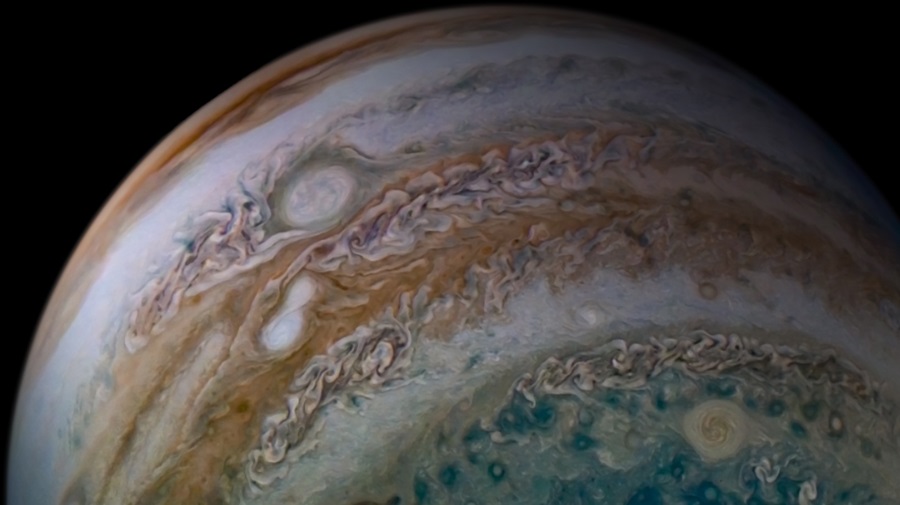

In the west, I see a bright golden-white star: the planet Jupiter. It’s lovely with just the unaided eye and easy to find on a spring evening. Through a telescope, you’ll see cloud bands, the Great Red Spot (a centuries-old hurricane bigger than Earth), and Jupiter’s four Galilean moons, named for Galileo Galilei, their discoverer. You don’t need a telescope to see the moons; you can see them with binoculars — just steady them on a railing or tree branch.

Right now, when science and reason are casually derided and discarded by some of our fellow citizens, it’s never been more important to look at these moons and consider the history of their discovery.

Galileo was the first person to aim a telescope at Jupiter. The year was 1610, and his was a crude instrument, one of the first made, but he was a keen observer. He noticed four pinpoint stars in a line close to Jupiter; they were invisible to the unaided eye. Galileo was also a patient observer. Watching these four stars over the course of hours, he saw something astonishing: they moved.

They did not move across the sky as all stars do; they moved with and around Jupiter. Over several nights, he observed them pass in front of Jupiter, disappear behind it, and reappear on the other side with clockwork precision. He realized that they were moons of Jupiter, just as Earth has a moon. And he understood that they were evidence that Earth was not the center of the universe, around which all celestial objects revolved.

That’s when Galileo’s troubles began.

Natural philosophers (an old term for what we now call scientists) since antiquity had held that Earth was the center of the universe. The idea felt right even when the available evidence didn’t support it; sometimes feelings win the day. Aristotle in 4th-century-BCE Greece and Claudius Ptolemy in 2nd-century Roman Egypt were the two most influential thinkers on this matter. Even more important, at least for Galileo, was that the Aristotelean Earth-centered universe was the orthodox position of the Catholic Church, the dominant political institution of Renaissance Italy, where Galileo lived. This view dovetailed nicely with passages in the Bible that placed Earth at the center of the universe. The Church considered any other idea to be heresy, subject to prosecution.

But Galileo now knew that some objects circled something besides Earth. It was a simple but powerful discovery. Shifting his perspective from Earth-centered to heliocentric (Sun-centered) unlocked a clearer, more accurate understanding of the universe and solved several persistent puzzles about the motions of certain objects in the sky, especially the planets.

Galileo was not the first person to see the potential of heliocentrism. Nicolaus Copernicus had published the idea in 1543, shortly before his death. Galileo was aware of Copernicus. And now he had something Copernicus didn’t: empirical evidence. So, he formulated a hypothesis, wrote up his notes, and published the results for others to consider and test: a fine early example of the scientific method, arguably the greatest human invention since writing.

The Catholic Church was not impressed. It banned Galileo’s book and warned him to abandon heliocentrism. Galileo was a scientist, not a revolutionary. He dropped the controversial idea and pursued other important research. But 10 years later, he published a new book about heliocentrism that took the form of a dialogue between a skeptic and a proponent of the theory. It was a clever use of a rhetorical technique made famous by Aristotle, although this time it was used to refute the Aristotelean world view.

The Inquisition had not forgotten Galileo. He was summoned to Rome to answer charges of heresy.

It is a common and appealing misconception that Galileo defended science before the Inquisition and refused to recant. But the opposite is true. Faced with torture and possible execution, Galileo maintained that he did not believe in heliocentrism and that his book was actually intended to disprove it.

It was a weak gambit. After all, the heliocentrism skeptic in the dialogue had the unsubtle name of Simplicio, and the inquisitors were not persuaded. Galileo was convicted and sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life. He was allowed to live only because well-connected friends intervened to reduce his sentence.

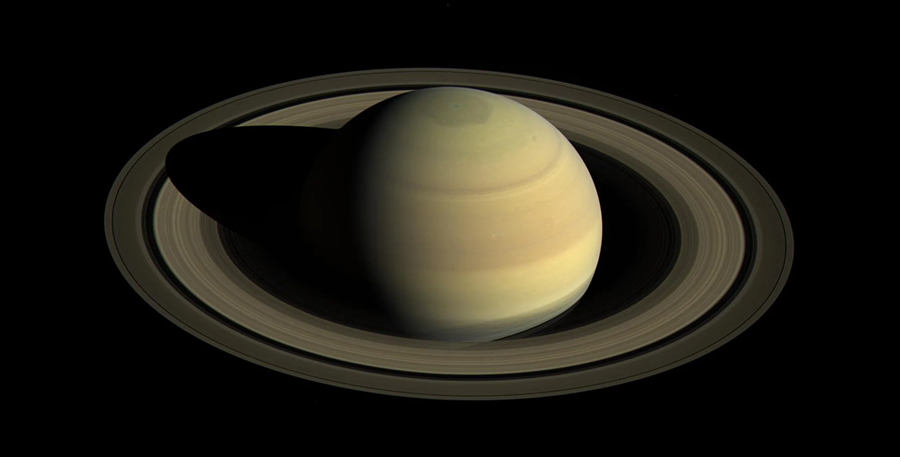

In the centuries since Galileo’s discovery, our perspective broadened in tandem with developments in technology. Earth orbits the Sun; planets in other solar systems orbit other stars; all stars orbit their host galaxies.

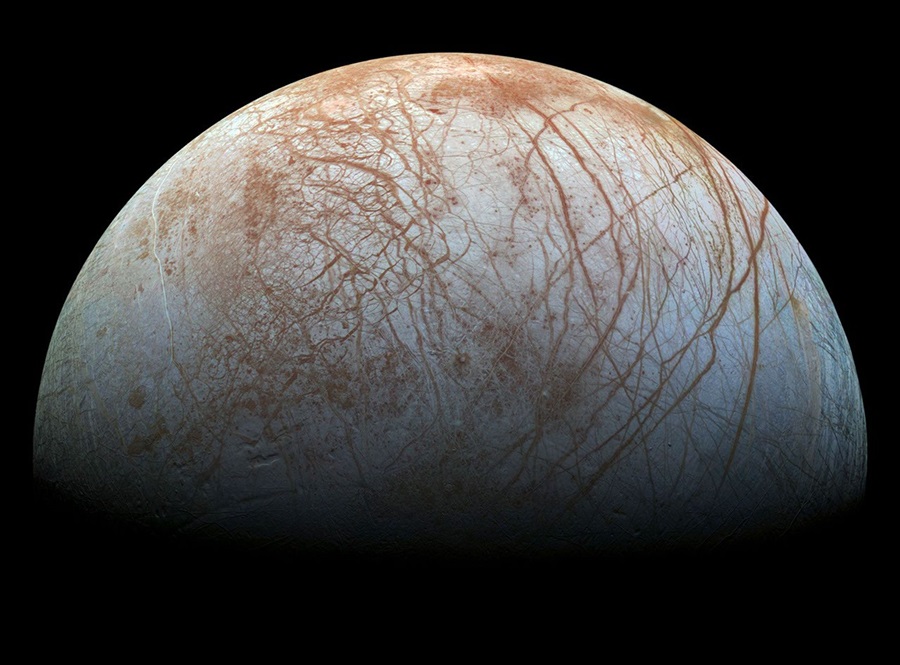

Now we know that 95 moons orbit Jupiter, though most are too small to be discerned using telescopes like Galileo’s or mine. And none of the others compares to the Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, each a fascinating world. Three may harbor life in oceans beneath a thick icy crust. NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft is on the way to Jupiter to search for proof of an ocean under Europa’s ice, and, if we’re lucky, it could detect hints of extraterrestrial life. If you have binoculars, steady them and look at Jupiter; you’ll see one or more of these moons.

Facts have a liberal bias, as more than one modern-day satirist has said. Galileo certainly seemed to know this, as did countless others before and after him. It’s been an inconvenient truth to those who have clung to power throughout recorded history. I admire Galileo’s brilliance, and I do not judge his capitulation to the Church. Sadly, the Inquisition, in a new guise, is with us still today; ignorance, intolerance, cruelty, and a slavish adherence to dogma are the new horsemen of the apocalypse. What inquisition would I face to speak truth? What values would I stand up for? Whom would I defend? I watch the dance of Jupiter’s moons and wonder.