There’s some serious art hanging in the kids’ section of the Wellfleet Public Library. A mural by Juliet Kepes features stylized animals cavorting on washy fields of color. It’s light and playful, but undergirding it are ideas and sensibilities deeply rooted in Wellfleet’s midcentury Bauhaus community.

“They were that interesting mix of high academia and low-brow humor,” says Janos Stone about his grandparents, Juliet and György Kepes. Juliet was best known as an illustrator and children’s book author, while György was a painter, designer, and influential thinker.

“A lot of their artwork was inspired by Klee and Chagall, the playful side of modernism,” Peter McMahon says of the Kepeses and their peers. McMahon, the founding director of the Cape Cod Modern House Trust and coauthor of Cape Cod Modern, has researched the community of designers that spent their summers together in Wellfleet.

The Kepes house, on Long Pond, was designed by modernist architect Marcel Breuer in 1949 and remains in the family, owned by the Kepeses’ children, Julie Kepes Stone and Imre Kepes. (It was described in an article by Jenny Monick in the Oct. 21, 2021 Independent.)

The flat forms in Juliet Kepes’s mural recall Matisse’s cutouts. The block-like bull, dominating the left side of the painting, grounded in an earthy brown, could be a cousin to Picasso’s bulls with their multi-perspectival approach to form. A cat rendered with a meandering line plays nearby. Each animal’s personality is expressed through its form and materials. Opposite the bull, a swan with a high-reaching, slender neck dominates the right side of the painting. In one corner, an elongated fox chases a rabbit, its tail represented three-dimensionally by a puff of cotton.

This painting is actually a re-creation, the original lost. It gained attention after being featured in a 1949 Life magazine article titled “Fun Room.” The article described the bedroom that the Kepeses designed for their daughter in their Cambridge home. It included a black-and-white photograph of the couple in front of the mural. The room also included a large clock and climbing tree. According to the article, it was “a talented couple’s idea of what a child’s nursery should be like.”

In 2012, the Museum of Modern Art in New York included the Kepeses in the exhibition “The Century of the Child,” which provided an “overview of the modernist preoccupation with children and childhood as a paradigm for progressive design thinking” in the 20th century.

“My grandparents were curated into it for the progressive and experimental playroom they created for my mom when she was a child,” says Stone. “We had a few artifacts left from the room. MoMA curated in some of the artifacts and asked us to recreate the mural.” Janos, along with his brother, Nico, looked at images from the Life photo shoot, as well as a small sketch their grandmother made for the mural. “We still had that sketch, so we could figure out what the colors were because the photographic sources were black and white,” says Stone.

Like his grandparents, Stone is an artist and designer. His recent venture, Haus, is a flat-pack, washable children’s playhouse that, according to Stone, “facilitates open-ended child-like play.” Its utilitarian design and emphasis on interactivity hearken back to his grandparents’ experiments over 70 years ago.

McMahon explored the intersection of play and design in a 2016 exhibition at the Wellfleet Historical Society. Titled “The Children’s Room: Art and Design of Wellfleet’s Midcentury Children’s Books,” it featured Juliet Kepes’s mural alongside other original artwork by her and others. In putting together the show, McMahon discovered that there were about 200 children’s books created by this local midcentury community, most of them by women — the wives of architects.

“This was their creative outlet,” says McMahon. “It looks naive but is very sophisticated, almost intentionally primitive. They reflect the proto-hippie ethos of the time. The do-it-yourself attitude.”

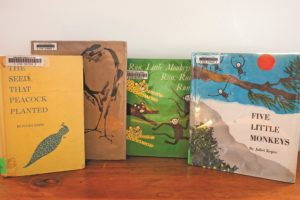

The Wellfleet Public Library has collected a handful of Juliet Kepes’s children’s books, including Five Little Monkeys, which won a Caldecott honor in 1953. Her books, too, feature colorful animals and reveal visual influences ranging from modern art to Japanese ink painting.

“She was heavily influenced by Asian art and brush calligraphy,” says Stone. “Her work reflects the Zen process of calligraphy, where years of practice guide the hand.” In tandem with this discipline, play and chance guided her creative output. This combination of rigor and spontaneity reflects Bauhaus ideas.

On one hand, these designers favored no-nonsense utilitarian design: “Form follows function.” But many of those architects were making children’s furniture and objects, says McMahon. Whereas in the Victorian era children were viewed as little adults in need of discipline, “Bauhaus was about encouraging creativity and, in some cases, trying to return to a childlike state,” he says. “Children were admired, almost envied.”

Kepes’s mural and the playroom for which it was created “was a very obvious experiment in open-ended, tactile, child-led play,” says Stone. “For most Americans it wasn’t something people were thinking about.”