A maximalist by nature, Julia Salinger indulges in all that she finds curious and delightful. She’s a voracious collector of paper ephemera and a compulsive creator. “I basically live inside an installation,” she says of her Wellfleet home and studio, which is jam-packed with artwork and personal effects.

Like the bohemian royalty of earlier times on the Outer Cape, she cuts a colorful figure around town wearing layers of bright patterned clothes and, on special occasions, one of her signature headdresses, piled high with flowers atop her abundant white hair.

When it comes to a vocation, she’s never played by the rules that favor specialization and singular pursuits. She’s been a therapist, music producer, researcher of Andy Warhol prints, playwright, poet, actor, DJ, and artist — among other things.

For most artists, such wide-ranging activity might result in diluted and unfocused efforts. That’s not what a visitor finds in Salinger’s current show, “The Insistence of Memory,” at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum. Here, her accumulated experiences, lifetime collection of stuff, and broad range of creative gestures materialize into a gestalt of an exhibition, conveying something that approaches the breadth of memory and a life fully lived.

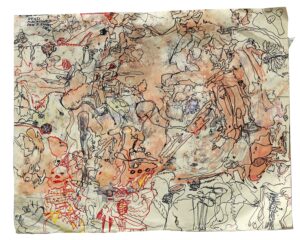

Ready, Set, Go — a drawing with ink, pen, and gouache — features Salinger’s impressive linework, which traces and layers a flesh-colored under-image of splattered and smeared paint. The busy lines meander across the page in an all-over composition, creating networks, coalescing, and then pulling apart to create other networks. Viewed in light of Salinger’s interest in memory, the image looks as if it could be a map of neural networks and recalls the way memory functions as something both fragmented and interconnected.

The exhibition comes together around Salinger’s use of lines rendered in all varieties of thickness and speed. They stretch over her paintings, drawings, and sculptures. They converge into detailed patterns, depict objects, render letters, and wander freely.

“I am drawn to her mark-making and how it pushes outside of the boundaries of whatever medium it is on,” writes Susie Nielsen in her curatorial statement. “Julia’s work is completely intertwined with the rest of her life…. It is one continuous line. It is one long poem or song lyric.”

In For Nabokov & The Butterflies at Large Salinger probes her emotional world in a sprawling image composed of collaged elements. Math homework that she did with her father, instructions for beekeeping, and a recipe for mayonnaise — all fragments of the composition — evoke nostalgia and domesticity. But the erratic lines and blood-red color throughout introduce other layers of emotion. One torn print of looping circles along a horizontal line suggests a spinal column and rib cage. “To me, this is like someone that’s dead,” says Salinger. “Someone in a war.”

Salinger picks up the theme of butterflies in another composition, When the Butterflies Fade. The text at the top reads: “There were 100s of butterflies on the walls,” a reference to the drawings of children at Auschwitz. The paint in this composition is smeared amid decorative designs and fragments of advertisements, with phrases such as “welcome aboard” and “sale.” Here, hope and despair, historical memory and commercialism, decoration and defilement exist together in an interplay that feels total and complex.

Salinger, who was born in 1959, grew up in the Bronx and came of age during the 1970s and ’80s. Her artwork vibrates with the experimental and frenetic energy of that time.

“New York in the ’70s was dirty, dangerous, and almost bankrupt,” says Salinger. Her mother gave her a lot of freedom to explore and also exposed her to the city’s cultural riches.

“My mother would take me to St. Mark’s for poetry readings,” says Salinger. She also went to children’s concerts at Carnegie Hall and took improvisational theater classes. “I remember the teacher saying, ‘Be a rubber band,’ ” says Salinger. “New York left such an impression on me. It was like a theater. It wasn’t homogenous.”

Her mother also exposed her to jazz, which became a focal point in her career for about 16 years. Salinger worked with musicians as a manager, producer, and publicist. When her mother died in 1997, she realized it was time to wean herself from the music business and begin pursuing her own art. Up to that point, Salinger had only taken one drawing class as an undergraduate at SUNY Purchase, but she had been making things her whole life. “My real temperament is as an artist,” she says.

Her experience in the music industry proved formative in her artistic development. “I saw how musicians lived and worked, their creative process,” she says. “I took in all of that. I could give myself freedom to make art like musicians give themselves freedom to improvise.” Influenced by the energy of free jazz and musicians like Ornette Coleman, Salinger began devoting herself to an art practice that deepened when she moved to Wellfleet in 2004.

“I have music in my head when I’m working,” says Salinger. “Do these beats, these rhythms sound good? That helps me build the work.” She improvises like a jazz musician by dumping all of her materials on a table. “I just throw everything on, mush it up like you do with a puzzle and then start picking things out that make sense to me,” she says.

Along with improvisation comes structure. “I’ve always loved to turn chaos into something organized,” says Salinger. “You can build an armature and then hang all of these things all over it. Because it has that basic structure it works.”

Salinger employs different armatures in her artwork. “Line is my anchor,” she says. Often, it’s a clarifying gesture. In some pieces, she uses the structure of a grid or limited color palettes (typically black and white, red, or green) to impose a structure on her freewheeling expressions. In this regard, the work harkens back to jazz in the way it alternates between chaos and rhythmic order.

Susie Nielsen, an artist, designer, and owner of Farm Projects in Wellfleet, curated the current show and helped to contain Salinger’s energy in what is a focused and digestible exhibition.

“She gets me,” says Salinger. “She knows she needs to rein me in.” But in the 200-page artist book accompanying the exhibition, Salinger lets it all hang out. “It contains all of the things that I do that relate to each other: the art, the writing, the gardening, the food, the music, the travel, all of that,” she writes. “It gives people a sense of who I am.”

The Music in Her Head

The event: “The Insistence of Memory”: an exhibition of work by Julia Salinger

The time: Through July 7; Fred Schiff Levin Lecture with Julia Salinger and Susie Nielsen, Thursday, June 13, 6 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission: $15