“In the Jewish tradition, the most harm one person can do to another is through lashon hara, which means ‘evil tongue or speech’ in Hebrew,” says Jonathan Gershon Stark, who usually goes by his middle name. “Lashon hara is considered to be worse even than murder, because a person’s sense of self is killed over and over again instead of just once.”

Stark has an ongoing photographic project he calls “Sticks and Stones,” which will be on view at a pop-up exhibit at Gallery 444 in Provincetown from April 18 to May 2, with an opening on Friday, April 23. It is meant to raise awareness of the prevalence and power of verbal abuse.

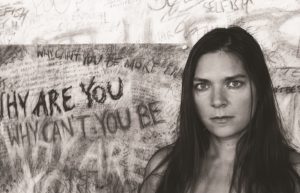

Abusive language, Stark says, does not have to be direct or include expletives. Subtle words, spoken just once, such as “Why are you so sensitive?” or “You are difficult to love,” are internalized. “My mission,” Stark says, “is to bring attention, in an artistic way, to this trauma.”

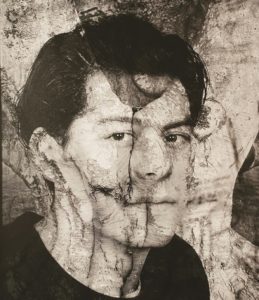

For “Sticks and Stones,” Stark, who is based in Providence, R.I., often takes photographs of participants against a backdrop of handwritten words of torment. Other images show the participant with the words that emotionally scar them inscribed on their skin. These are perhaps the most powerful.

In the words of fellow artist Michaela Clift, which Stark includes in the exhibit, “When someone verbally abuses you, it comes down to your skin. It does not matter what clothes you are wearing.” Stark also invited his friend and fellow artist Johnny Rivera to work on some of the photos. “He added a dimension of color, playfulness, and, at times, darkness,” Stark says.

The project has been cathartic for many of Stark’s subjects. Their visible reactions, he says, speak to how deep the pain caused by verbal abuse can run. He works with each of his subjects for as long as it takes for them to become comfortable enough to express the emotions evoked by certain words.

One woman, for example, had been told long ago that she was “not good enough.” Stark documented the words’ effect by writing them on her body one at a time. “First, I wrote good and asked her to express what she felt,” he says. “Then, I wrote not good, and asked her what it is like to be not good.” With those words, “You can be a rebel, and revel in that.” Finally, he wrote the entire phrase, not good enough, and she opened up to reveal the underlying hurt.

Stark was born in the Bronx, N.Y. Some of his earliest memories are of being transfixed by people in the subway. “I took the train with my mom down to Central Park in Manhattan,” he says. “I can still remember kneeling on the seat next to her, staring alternately at the faces, shoes, bodies, clothing of the people on the train. Every shape, size, color, and attitude.”

After his parents’ painful divorce, Stark lived as a teen with his aunt and uncle on Long Island, where he developed a love for the ocean. “I discovered surfing, and spent five years in the water, winter and summer. I became this weird mix of urban Jew and rocking surfer,” he says. His uncle saw his interest in art and gave him his first 35 mm camera. “A roll of film later, I was hooked,” Stark says. “I would walk around Lower Manhattan, photographing Italian men playing bocce and old women sitting on milk crates. I am, at heart, an artist who needs to engage the world directly.”

Stark studied photography and sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton, then took a master’s in film and broadcasting at Boston University. In his photography, he seeks to reveal the depths and layers underneath the surface we ordinarily perceive. Past work includes a “Zipper Project,” exploring what we wear on our bodies and the intimacies that are concealed, and “Skin Deep,” celebrating the human form.

A recent project called “Security” was inspired by Stark’s observation that security guards are most often seen “as automatons or servants” in our culture. He interviewed them and learned that “most were on their way to other careers and that their security job was just a way to pay the bills.” Stark invited them to come into his studio and pose — first, in their uniforms; then, in their own clothes. The transformation is startling, showing the extent to which a person’s humanity can be stripped by roles and uniforms.

Stark was married in Provincetown 10 years ago and visits regularly with his wife and young daughter. “Our hearts are here,” he says. He considers himself a devout Jew, and he sees his art as part of tikkun olam, the Jewish theological obligation “to make the world a better place — to restore its beauty.” He says that “Sticks and Stones,” which he hopes to expand and exhibit widely, is his “humble attempt to make a small contribution in that direction.” (Stark continues to seek participants for “Sticks and Stones”; contact him at starkview.com.)

“Ultimately,” Stark says, “in spite of the initial loss of power we can suffer as a result of how we were perceived, spoken to, and treated by others, we can, by embracing our vulnerability, through prayer, love, lovemaking, and art, find true power, the power over the only person we can have power over — ourselves.”

Body Language

The event: “Sticks and Stones,” a pop-up exhibit of photography by Gershon Stark

The time: April 18 through May 2; daily, noon to 6 p.m., Friday till 8; opening reception, Friday, April 23, 4 to 8 p.m.

The place: Gallery 444, 444 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free