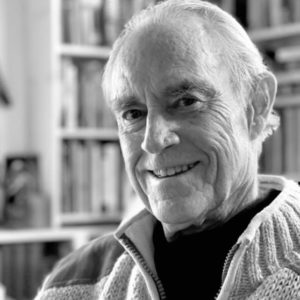

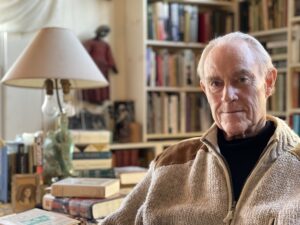

John Taylor Williams, known to all as Ike, died on Dec. 26, 2024 at his home in Cambridge, surrounded by family. He was 86.

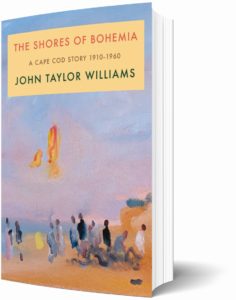

Ike lived much of every year on Bound Brook Island in Wellfleet at the home he shared with his late wife, Noa Hall Williams. His father-in-law, Jack Hall, who was at the center of a cluster of writers, painters, architects, vagabonds, political radicals, and sexual adventurers, introduced him to the Outer Cape’s avant-garde culture, which Ike immortalized in his 2022 book, The Shores of Bohemia.

Ike, who stood six-foot-six and was movie-actor handsome, was a literary lawyer and agent. But that only begins to describe who he was. He was deeply engaged with a wide range of cultural and political institutions, including the National Endowment for the Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art, the Huntington Theatre, the Boston Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, the Boston Book Festival, and the Prisoner’s Rights Project. He was the longtime co-chair of Provincetown’s Fine Arts Work Center.

Ike possessed what used to be called charisma. When he walked into a restaurant, heads turned as if there were an invisible spotlight on him, even if most in the room had no idea who he was. “People naturally wanted to be around him,” said his son Jared. “To walk beside him was to feel like you were at the center of the world.”

Ike combined a commanding presence and an almost dandyish penchant for tailored clothes with personal modesty. He was both pleased and embarrassed when GQ included him on its list of best-dressed men.

He quietly helped many people, the known and the unknown. One day, as he and Noa were emerging from an MBTA station in Cambridge, a newspaper seller said to Noa, “You have quite a guy.” She replied, “Thank you,” thinking the man was referring to Ike’s good looks. The man went on to explain that Ike, who passed by every day on his way to work, had noticed him limping and paid for knee replacement surgery. Ike had not told Noa or anyone else.

A Boxer’s Name

Ike was born in Cambridge in 1938 and given the name John Philip Taylor. His father died in a car accident when he was three. His mother remarried a widower, Merton Williams, when Ike was 11, and he changed his surname to Williams.

His stepfather, seeing unusual promise in the boy, paid for him to attend the Middlesex School, where he was active in sports, including boxing. It was his roommate and boxing enthusiast Mills Lane, later a professional boxing referee, who bestowed the nickname Ike, after the 1940s lightweight champion Ike Williams. The name stuck.

Ike was in the class of 1960 at Harvard, where his closest friend was Charles Jencks, who went on to become a distinguished landscape architect. Charles’s parents lived much of the year on Bound Brook Island, a stone’s throw from the home that Ike and Noa would inherit from Jack Hall. Noa’s best childhood friend was the Jenckses’ daughter, Penelope, a renowned sculptor who still lives on Bound Brook. But it was not Penny Jencks who introduced the couple.

Living in New York, Ike was part of the circle around Andy Warhol’s famous Factory, which included the African-American writer and artist Dorothy Dean. She knew both Ike and Noa, decided they would make a terrific couple, and contrived to introduce them.

According to family lore, Ike tried to persuade Noa to move to Boston. But Noa was in nursing school and was part of the New York arts scene. She kept saying that they were not engaged and she was not just going to live with him. Ike finally mumbled something to the effect that he wouldn’t be asking her to move to Boston unless he also wanted her to marry him.

It was not quite the romantic proposal Noa had been expecting, and she said so. Then she accepted.

An Unusual Agent

After law school at Penn, Ike worked for a succession of Boston firms. He and Noa bought a Victorian house near Porter Square. The Red Line had not yet been extended to Porter, and it was still very much a working-class neighborhood. Ike’s three sons grew up in the same house where he died.

At Palmer and Dodge, Ike represented publishing clients and created what amounted to a literary agency inside one of Boston’s top law firms. In 1990, with his friend Jill Kneerim, he set out on his own. The office on Canal Street had two names, the literary agency and a law firm with partner Paul Sennott. Though he was better known than either of his partners, the enterprises were called Kneerim and Williams and Sennott and Williams. Ike, chacteristically, was listed second, alphabetically.

When I engaged Ike in 2011 as my agent for the book that became Debtors’ Prison (Knopf, 2013), he explained that he could represent me either as an agent and charge the usual 15 percent of royalties; or, if I had publishing contacts myself, I could just retain him to negotiate terms and he would bill me by the hour, saving me a lot of money. It was classic generous Ike. I know of no other author’s agent who operates that way.

Ike’s list of clients reads like a party you’d give anything to be invited to: Norman Mailer, E.O. Wilson, Howard Gardner, Tim Berners Lee, James MacGregor Burns, Howard Zinn, Frances Fitzgerald, Nigel Hamilton, and Sara Lawrence Lightfoot, among others. His clients typically became friends. As an intellectual property lawyer, Ike also helped turn books into movies, including Captain Phillips, starring Tom Hanks, and Public Enemies, with Johnny Depp and Christian Bale. He found time to co-author an authoritative textbook on publishing law.

The Outer Cape is still thick with writers, artists, and political and sexual radicals, and Ike seemed to know every one of them. But somehow, sitting down with Ike over a meal or over a contract, you never felt rushed. I have no idea how he did it.

His longtime assistant, Hope Denekamp, tells of 12-hour days with a pause at 7 p.m. or so. “Then the Wild Turkey would come out,” she said, not referring to birds. They would take a bourbon break, then go for another few hours. “My dad could put away a massive amount of booze,” said Jared, “but I’ve never seen him drunk.”

Late in the evening, Ike would sometimes leave an intemperate letter for Hope to send out. She said she would hold it and gently suggest in the morning that he tone it down. Ike would.

“He worked long hours,” said his son Nat, “but he was a private guy, too. He spent a lot of time recharging.” His son Caleb added, “The parts of him that remained vulnerable never hardened with time.”

Because he combined legal and negotiating skill with personal grace, Ike was superb at bringing people together. Hunter O’Hanian, former executive director of the Fine Arts Work Center, decribes a now-thriving institution that was unable to pay its bills, with crumbling buildings and factional divisions, when Ike agreed to become its board co-chair in 2003. “He was a good donor but a great organizer, being smart about solving problems and winning everyone’s trust,” O’Hanian said. “He helped forge the sustainability that we have today.”

Warm-Hearted Sins

Ike was one of the great raconteurs, partly a natural gift and partly because of all the people he knew. Ike pulled together his penchant for storytelling with his fascination with Cape lore in The Shores of Bohemia, which got the front page of the New York Times Book Review.

The book begins with a fine history of how the Outer Cape became a magnet, first for artists because of the magnificent natural landscape and light and then for writers and radicals, especially as World War I temporarily diverted bohemian traffic that might normally have headed for Paris. As Ike recounts, there was a Provincetown-Greenwich Village axis that ran both ways, with Village denizens coming to the Outer Cape for the cheap rent and arts scene and the Provincetown Players relocating to MacDougall Street in the Village.

The later parts of the book are less a definitive history of the Outer Cape than Ike’s personal memoir. The best chapters rely less on what he learned from other histories, biographies, and letters than from what he knew personally.

At local events after the book was published, members of the audience sometimes objected that Ike had gotten this or that detail wrong. He was gracious in hearing these corrections. Though the book is occasionally gossipy, the errors tended to be mistakes of exuberance, not of malice. Mostly, people forgave him.

I’m reminded of a line of FDR’s: “The immortal Dante tells us that divine justice weighs the sins of the cold-blooded and the sins of the warm-hearted in different scales.” To the extent that Ike had sins, they were sins of the warm-hearted.

Noa Hall Williams died in 2014. Ike later married Caroline Courtauld, a longtime family friend and Burma scholar who lived mostly in the U.K. Ike, in his 80s, managed a loving trans-Atlantic commuter marriage.

In his last months, Ike’s health gave out, as multiple systems failed. He’d long suffered from back problems. He was blind in one eye from a childhood accident, and he was going deaf. He had a couple of bad falls.

Ike bore his ills with grace. He never began a visit with an organ recital. He lived hard and lived well. Jared recalls a favorite Ike credo: “We’re not here for a long time, we’re here for a good time.”

Ike is survived by his sons Caleb, Jared, and Nathaniel, several grandchildren, and his wife, Caroline. There will be a public memorial in the spring. Summing up Ike’s life, his Wellfleet compatriot and literary scholar Nicholas Delbanco quotes Shakespeare: “He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Jan. 9, misspelled the last name of former Fine Arts Work Center Executive Director Hunter O’Hanian.