“I paint like a child,” says John Choly with a smile and a twinkle in his eye. “And I own that.”

In his Provincetown studio, he is surrounded by shelves of paints, crayons, markers, beads, wrapping paper, shells, stones, ribbons, glitter, and Play-Doh. “Picasso once said that he made his best art later on in life, when he returned to painting like a six-year-old,” Choly says. “I really went with that.”

For the past three decades, Choly has been painting bold, colorful hearts. His fascination with this simple shape goes back to 1989, when he began to paint hearts on handmade greeting cards. “One day, I was in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and saw a huge heart painting by Robert Rauschenberg,” Choly says. “It was dark and bloody, but it was still a heart. I realized then that I can use hearts in my artwork, not just in pretty little handmade cards.”

Since then, painting hearts has become his “grass-roots underground movement of love,” he says on his website, cholyheartsandmoons.com, where he sells his work. Choly also puts hearts on mugs, T-shirts, greeting cards, and other items that he offers for much less than a painting.

“I’ve had thousands and thousands of pieces of my art go out in the world,” he says. “Every now and then, someone sends me a story about how my work has touched them and brought joy into their life. When I hear that, I know that I’ve done something positive.”

Though Choly says that he sometimes worries that his work is “too cute and trite instead of deep,” his hearts are neither clichéd nor commercial. À la Picasso, they have some of the magic parents recognize in their children’s art. Such uninhibited creativity usually disappears at age 10 to 12, when the belief that, to make art, you “have to be good at it” takes over.

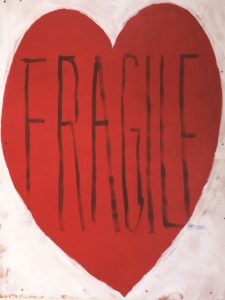

Choly’s hearts also contain messages. The word “FRAGILE” is painted across one bright red heart in light brushstrokes. Choly is the main packer at his retail day job. “Shipping has nearly doubled since Covid,” he says. “I found myself putting ‘FRAGILE’ stickers on many boxes, and I thought about how fragile our hearts and lives are.”

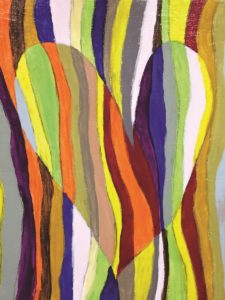

Another heart is made up of colored stripes with a striped background, representing “the oneness of the entire universe,” Choly says.

Born in 1959, the son of second-generation Ukrainian immigrants, Choly grew up in Yonkers, N.Y., then Connecticut. His mother, a former nun, introduced him to art, crafts, and museums. By the time he was 12, Choly knew that he wanted to lead a creative life, and spirituality and art have remained at the center of his world. Though he’s not religious anymore, he believes in “something that connects us all,” and aims to make this manifest in his art.

He attended an all-boys Jesuit high school, an experience he still values. “The Jesuits are philosophers and educators,” he says. “I took classes on atheism, death, and dying. We were taken to museums in New York City. Our teachers wanted us to think and to challenge our minds.”

One art teacher became his “guiding light” — Betty Kachmar, who believed all her students should experience making art and be free to “just try things out.”

Undecided about whether he wanted to become a writer, artist, or actor, Choly studied theater and elementary education at Saint Leo University in St. Leo, Fla. But instead of pursuing acting or teaching professionally, Choly took jobs that would give him the financial security and free time to focus on his art. He took a watercolor class and did landscapes that, much to his surprise, sold well. “I was like, what? I didn’t want it at first,” Choly says and laughs.

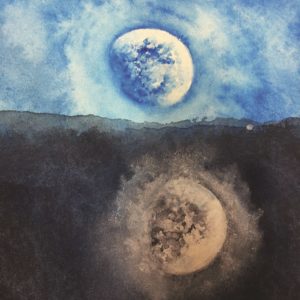

He spent a decade living in Providence, R.I., where he began an ongoing series of moon paintings in watercolor inspired by nighttime walks. In 1997, he painted the moon every night for 365 days, a project that was shown at Cortland Jessup Gallery in Provincetown in 1998. Choly’s moon paintings explore the shape’s expressive potential the same way as his heart paintings. As the moon waxes and wanes, he sees it mirroring complicated human emotions.

“I have known mild depression since my teenage years,” he says. “There is always darkness and light in everyone, and, in darkness, the light has to find a way to come through.”

In the fall of 1999, Choly decided to look for a year-round rental in Provincetown. In what he calls “one of the many miraculous moments of my life,” he found both a place to live and a job.

“When I was coming out in 1983, a friend brought me here for a week,” he says. “And I thought, oh, my God, what an incredible place. What drew me even more than the gay community is the way artists are honored. Even car mechanics understand artists here. I’ve lived in places where people look at you like you have three heads when you say you’re an artist.”

It’s more about people for him than the landscape. “I joke about this,” Choly says. “You know how artists say there’s a certain kind of light here that they love? Well, by the time I get to the studio after work, it’s dark. So, I have to paint with my inner light.”

He chuckles and adds, “I say funny things, but it’s true.”