PROVINCETOWN — So, this is back in the early ’60s, down in Connecticut, in some kind of factory. A bunch of guys eat lunch every day at the same table. One of them, kind of a doofus, has just bought a new Pontiac. He raves about this car every day, on and on, about this feature and that feature, and the really great mileage he is getting — 18 or 19 mpg.

He goes on like this for so long that his coworkers decide to fix him but good. They secretly add a few gallons of gas to his car every day. Now, at lunch, he is reporting mileage off the charts: 25, 27 mpg. He is absolutely raving, while they snicker into their sandwiches.

They continue until the guy is getting 35 or 40 mpg. He goes to the dealer to report this miracle, calls the newspapers and radio stations, contacts engineers. Then the next phase: over the next few weeks, they begin gradually siphoning off gas so that his mileage plummets. He can’t believe it. He is crazed. And they enjoy every minute of it.

This is a Joe Bones story. I don’t know if it is true, and I don’t care.

He had a million stories. Another was about a guy who got drunk and passed out so many times that his friends got tired of it and decided to fix him good: they bought a used parachute at an Army-Navy store and the next time he passed out on them they put him in it and hung him in a tree — to wake up the next day and wonder.

Joe’s stories are out there, but he has left us. He never ran out of material: jokes about golf, doctors, lawyers, animals — you name it. He could go on all night at the Beachcombers’ Club, sitting in front of the embers of a dying fire — and he often did.

Since Joe’s untimely death in Haiti last Wednesday, Facebook has lit up with testimonials. One phrase is repeated: “Larger than life.”

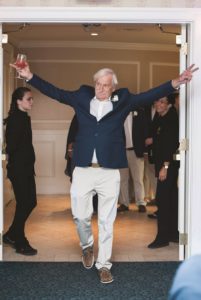

What does that mean? How exactly can one be larger than life? Perhaps it means that your spirit is too big for the body you were given, that your presence extends beyond your natural boundaries, so that when you walk into a room people will think, “What just happened here?” Or perhaps your life has had to play out on more than one stage, in multiple arenas and dimensions. Joe Bones personified both traits.

There are so many Joe Boneses, and different collections of people who knew him in his various guises. First, there is Joe the whale watch captain. He started as a mate on the Portuguese Princess back in 1984; his actual title was “mate-musician,” because he always brought his guitar on board and serenaded the passengers. When he got his captain’s license in 1987, he ran the boat but did not give up the serenading. Usually this was on the way back from the whales, starting at Race Point and then into the harbor.

On his very first trip as captain, he encountered a pod of orcas, 50 or 60 of them, and these rare creatures had to be entertained, so he played for them. Nobody has seen a group of orcas that large since.

In those early days of whale watching, Joe would strike out for “fresh whales,” usually heading east, away from the other boats. “Goin’ east” is known to this day as a “Bonesie move.” Whale watch captains are a curious lot, mixing camaraderie and competition. Joe enjoyed the greatest respect from all the captains.

Then there is Joe the entertainer. He was an early member of the Provincetown Jug Band, more recently of Willie and the Po’ Boys, and, finally, the Broke Brothers. Sometimes, he went right off the boat and into the Surf Club, the Governor Bradford, or the Old Colony, or onto the Portuguese Festival stage to play. Some of his creations — “Lookin’ for the Hot Spot,” “The Silver Fox,” “Eddie O’Hara,” “Temporarily Blue,” — will never be forgotten. He was a natural improviser, at ease on stage, and knew how to play a crowd, large or small.

Joe was extremely fond of rum. He was a prodigious drinker with profound stamina who rarely showed ill effects, while those trying to keep up lay wasted about him. I can still see him at his favorite seat at the bar at the Old Colony Tap. (When Joe once quit drinking for a brief period, I advised owner Lenny Enos that he should apply for a disaster relief loan.)

He was irresistible to women and esteemed by men. He was perfect in himself, absolutely genuine, which made for a kind of magnetism. You just wanted to be with him.

Everybody had a piece of Joe Bones, but there was a part he kept to himself (and for his daughters). He was never happier than when he was out windsurfing or sailing in the harbor. And then, he sailed away to Haiti. He spent large portions of the last 10 years in that country, going at first to participate in the relief efforts after the earthquake and falling in love with the people and the way of life. He was beloved there, known as “Papa Joe.”

The world that produced Joe Bones no longer exists. Like no one else (well, maybe Eddie Ritter), Joe dragged the essence of the ’60s and ’70s into this tamer century. He had a great life.

I feel utterly sad for those who will never see him casually walking down Commercial Street on his big shoeless feet with their thick calluses, his shoes tucked under his left arm, a smile on his face, with not a care in the world.

Joe Bones is gone. What a sorry place this seems to be now.