“One way or another, people have more poetry in them than you might think,” insists Robert Pinsky.

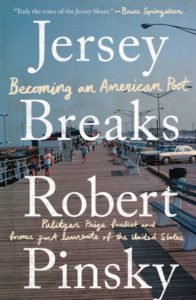

In 2000, this conviction prompted Pinsky, then the United States Poet Laureate, to invite people across the country to send him a favorite poem along with a brief statement of why it spoke to them. His call elicited thousands of responses and yielded a book that included 200 poems and was accompanied by a video series in which dozens of ordinary Americans explained their selections and read them aloud. This same conviction about poetry’s abundant presence and democratic distribution animates Pinsky’s memoir, Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet, published in October by Norton.

The author of 10 books of poetry and almost as many prose volumes exploring how poems sound, work, and live in the world — and an eloquent recent devotee of the beauty of the Outer Cape — Pinsky has a great deal of poetry in him. But you might not have thought that likely, he contends, had you known the circumstances of his birth and upbringing. His entertaining grab-bag of a memoir begins with a question: “Given my background, a friend asked me, how is it I became a poet rather than a criminal or an optometrist?”

The eldest son of a lower-middle-class, non-observant Jewish family stuck in a cramped apartment in the declining beach resort of Long Branch, N.J., Pinsky grew up in the care of an ambitious and frustrated mother, a beleaguered optometrist father, and a gun-toting grandfather locally notorious for bootlegging and bigamy. Pinsky’s parents compensated for their lack of social and economic status by creating a family culture of wisecracks, put-downs, and other genres of aggrieved verbal wit.

“I had the good luck,” Pinsky writes, “to be raised among expert joke-tellers, complainers, arguers, schmoozers, boasters and liars.”

For Pinsky, sensitivity to “the sounds of sentences” is what generates poetry and makes a poet. An American poet must register and recreate “the clangs and chimes of our profoundly mongrel, improvised, and Bible-ridden American language” — the “yacking voice” of our culture’s “erratic orbit between the cross-fertilized poles of democratic genius and populist vulgarity.” The young Pinsky’s education in those clangs and chimes occurred not only at home but in the streets of immigrant-rich Long Branch, with its “mishmosh” of Italian, Irish, Jewish, Black, and white Protestant families. Exposure to the ethnic diversity of his neighbors also attuned Pinsky to the auditory diversity of their names and led to his perception that different-sounding surnames carried different degrees of status.

This habit of thinking about names, which Pinsky would later regard as “essential to my work as a poet,” may have begun with his reflection on the relationship between his father, Milford Pinsky, and his father’s brother Morton, who had changed his name to Martin Penn. Anglicized names typically conveyed a more secure imprimatur of whiteness, he notes, as in the case of the Bernstein family, who became the Barnstones.

“In the magical sounds of words,” Pinsky writes, “that slight change can transform the feeling from a lower Manhattan deli to a Northumberland farmstead.”

At the same time, he learned early that “the Protestant-sounding names of Black people,” with their “nightmare history in slavery,” failed to afford them respect or protection. Still, he wonders provocatively, might the police have proceeded differently had the name on the Louisville apartment lease been Elizabeth Taylor rather than Breonna?

For all his achievements, a part of Pinsky remains the child of his striving, boasting, insecure, razor-tongued parents — the same wise-ass adolescent who liked to show up his less clever teachers. His episodic and eclectic “song of myself,” like Whitman’s, contains multitudes, including its share of name-dropping and brags — the make-your-own-adventure computer game he designed that players compared to Dante’s Inferno; his featured voice and avatar in an episode of The Simpsons. But these moments in Jersey Breaks are more often engaging than annoying, both because Pinsky frankly acknowledges his susceptibility to “a spirit of social defensiveness and aggression” and because, as he argues, this spirit, too, has its place in the national voice: “a traditional American response to being looked on as a hayseed or as an immigrant or a wage slave or an actual slave or a hillbilly or an ethnic outcast.” He both confesses and shrewdly exemplifies his simultaneous disdain for and guilty enjoyment of the trappings of celebrity when he remarks that his friend (and Nobel laureate) Czeslaw Milosz helped him “understand how the candid pleasure of a stroked ego might blend with a skeptical amusement at worldly shallowness.”

At its best, Pinsky contends, poetry “welcomes conflict, paradox and negation” and “reminds us of something beyond any particular feelings and ideas” — something “always in process, headed somewhere new,” like language itself. He cites with approval a review of his work that describes it as “roam[ing] over the earth devouring experience with omnivorous reverence.”

Pinsky’s own considerable roaming, underwritten by his professional success, has taken him from the gritty Jersey beach town of his youth to a home in Cambridge and summers in Truro. In a 2019 essay on the virtues of Cape Cod, channeling his family expertise in boasting and lying, Pinsky adopts the persona of a year-rounder: “We natives don’t dislike the Summer People,” he writes, but “feel superior to them,” regarding them “something like the way a dairy farmer looks at cows.” But he comes clean a few paragraphs later: “I grew up in an ocean resort in New Jersey, but on the Cape I have only the provisional, if not humiliating, status of a Summer Person.”

It’s a self-assessment that sums up Pinsky’s view of the province of poetry: conflict, paradox, negation; the giddy oscillation between superiority and humiliation; and the song of America itself.