PROVINCETOWN — Jeff Peters is a bit of a name dropper. Eileen Myles, Michael Cunningham, Christina Clancy. “Do you know Christina?” he asks. “Well, she’s the author of The Second Home, a novel set on Cape Cod — which, by the way, is being adapted by Sony into a mini-series.”

To be clear, Peters’s name-dropping doesn’t stem from some obnoxious impulse to impress. It reflects, instead, how excited he is about art and how much he admires the people who make it. If he drops names, it’s only because he wants to share all of that with you.

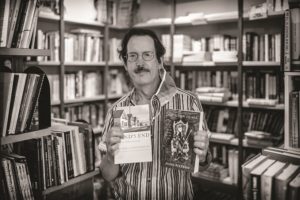

The thing is, you really might run into Christina Clancy one day at East End Books, the waterfront shop with floor-to-ceiling shelves neatly stacked with crisp, colorful hardcovers, owned and tended by Peters.

“That’s what I love about Provincetown,” says Peters, who is usually clad in an elaborately patterned button-up shirt. “You could be in my store and see John Waters one day, Michael Cunningham on another day, or Sarah Schulman or Chloe Grace Moretz on another.

“It’s one of the things that makes this town so magical,” he says. “In Provincetown, you’re less than one degree of separation from everyone.”

Peters’s mission at East End Books is to make that closeness real for everyone. The store doubles as an event space. Peters hosts talks with recently published authors and what he calls “literary salons,” in which two artists working in different genres (say a writer and a musician, or a filmmaker and a thespian) discuss their work. These are moderated by Peters and followed by drinks and dinner for all.

Even before the pandemic moved all our lives temporarily online and permanently brought the word “livestream” crashing into our lexicon, Peters was livestreaming his East End Books events.

“I grew up in Tallahassee, where there weren’t many independently owned bookstores,” he says, “and I would see literary and cultural events advertised in the New York Times or the Boston Globe or Los Angeles Times, and I would just think to myself, ‘Boy, I wish I could go. I wish I could see that author — what an opportunity it would be to talk to them.’ ” He wants people to be able to see and hear writers and artists in a way that wasn’t possible back then for him.

Peters is preoccupied with screen adaptations of novels. He talks spiritedly with a customer about how the book she is buying, Normal People by Sally Rooney, was adapted last summer into a brilliant Hulu mini-series. Rooney wanted the novel to become a film, Peters says, but professionals advised her that a mini-series, which can run a course of up to a dozen one-hour installments, would be much more suitable for capturing the nuances of the story line than a two-hour movie.

“That’s the direction we’re moving in,” he says, “mini-series and not movies.” Later that day, Peters admits he can’t say too much, but he’s in cahoots with others to turn Julia Glass’s novel Three Junes into a mini-series.

Peters grew up reading a ton — books were a refuge for a gay kid living in a place where it’s not safe to be gay — but he also grew up around film. His father ran an art cinema. He remembers sitting in the projection booth with his father one night and watching a film go up in flames. “I was like, ‘Uh-oh, that’s not such a good thing,’ ” he says. But sitting in that booth sparked his interest in film, and especially documentaries.

He has made several documentaries, he says, with a social justice bent and inspired by personal experience. Peters studied law and started his career working for Bob Butterworth, then Florida’s progressive attorney general. When word got out to the American Family Association, which has been listed as an anti-LGBTQ hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, that there was a gay man in the attorney general’s office, the association campaigned for his removal. “I was under attack,” Peters recalls. “They called me an ‘enemy of God.’ ”

Butterworth stuck by him and the outrage abated. It was a lesson, Peters says, in the importance of staying politically alert.

Peters says that the bookstore is his way of bringing film, literature, and politics under one roof. “I’m able to put all my worlds together into this one little store,” he says.

Against the octopus-like Amazon, perhaps it’s the intangible and non-monetizable things, the connections and conversations, that are most at stake. They’re what Peters is here to uphold. “In the store, I get to have so many wonderful conversations with so many wonderful people,” he says. “And if someone wants to know a painter or a writer or an architect, I have a contact I can share with them.”