On Nov. 11, 1620, the Mayflower arrived in Provincetown Harbor. Four hundred years later, we — most of us, anyway, on the Outer Cape and all across the nation — think of the ship’s passengers as one homogeneous group of capital-P-Pilgrims: a tribe of big-buckled, big-dreaming religious dissidents. They abandoned their homeland for the sake of high ideals; they washed ashore in search of unprecedented freedom. We call them “Pilgrims” and “Puritans” interchangeably, and, either way, they dominate near every telling of our early history.

But we often overlook this key, if not-as-charming, part of the story: only about half of the Mayflower’s passengers even remotely fit that description.

Conflicting accounts of the number of children aboard the Mayflower make precise record-keeping difficult. But of the 102 passengers aboard the ship, only 37 were Separatists, English Protestants who fled to Leiden during the Twelve Years’ Truce, then became America’s Puritans.

Thirty passengers (among them Miles Standish, Richard Warren, Stephen Hopkins, and John Billington) were non-Separatists. And another 17 were indentured servants, apprentices, and wards. Those two groups, which combine to account for the majority of the “Pilgrims,” actually had a fair amount in common.

The non-Separatists were largely recruited by London merchants to assist the fledgling colony; they were driven to America’s foreign shores not by religious fervor but by pure economic incentive.

Some of the servants, apprentices, and wards aboard the vessel would have likely subscribed to their masters’ religious beliefs; some would likely have had very little say in their voyage to a new world. But some of the servants, apprentices, and wards had the same reasons for coming to America as did the wealthier non-Separatists. They wanted new starts, adventure, the chance to make something of themselves in a fresh and foreign land. Except they lacked something crucial: money.

So, a number of them struck deals with the Mayflower’s better-off passengers. In exchange for the payment of their fare, they’d become indentured servants, committing a certain number of years (in most cases, that specific figure has not survived history) to working for the payer’s family.

The drive here was not high-blown idealism. This was not the pursuit of unprecedented freedom. This, from some of America’s earliest European settlers, was pure hustle.

One of the indentured servants who bartered his way across the sea was a man from Fenstanton, Huntingdonshire, England, named John Howland, who would have been in his early 20s during the ship’s passage. Records of his early days are few, but it seems that his opportunity to set sail to America arose from pure coincidence.

“John Carver, the first governor of Plimoth Colony, lived in Leiden with the rest of the Separatists,” said Peter Arenstam, executive director of the Pilgrim John Howland Society, a lineage organization for Howland’s descendants. “Carver went to London to make final arrangements for the Mayflower to depart, and that’s likely where he met John, who convinced him to take him on as an indentured servant, essentially paying his passage in exchange for labor.”

The Mayflower passage was not a pleasant experience for any of the passengers. Space was limited; food was abysmal; seasickness reigned. Howland, though, had a particularly miserable time. According to William Bradford’s journal, Howland — a “lusty young man” — came above decks during a storm and, with a great heel of the ship, was thrown overboard.

The crew’s negligence saved Howland; he grabbed hold of a topsail halyard trailing in the water, and sailors hauled him back to the Mayflower’s decks. He managed to stay out of the water for the remainder of his journey to Provincetown, then Plymouth.

Historians haven’t been able to determine how many years of work Howland owed to the Carver family. But it doesn’t really matter. Half of the Mayflower’s passengers died during their first winter in Plymouth. John Carver and his wife, Catherine, were among the unlucky, and left no Carvers to carry on their legacy — or the terms of Howland’s contract. Which left him a freeman and the owner of the Carvers’ house by the spring of 1621, after serving barely half a year of his indenture.

From there, Howland moved quickly. He married Elizabeth Tilley — daughter of John Tilley and Joan Hurst, Separatist Mayflower passengers, in 1623. She was 16, he likely 28. They had 10 children, each of whom survived to adulthood, no small feat in 17th-century New England.

Howland — among the lowliest Mayflower passengers — made a name for himself in Plymouth colony. He served as a personal secretary to Gov. Carver before his death, was elected deputy to the Plymouth General Court twice, served as a sort of one-man draft board, approving men to fight in King Phillip’s War, and, in Arenstam’s words, “just ended up owning an awful lot of land.”

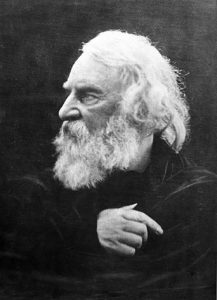

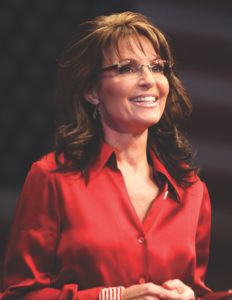

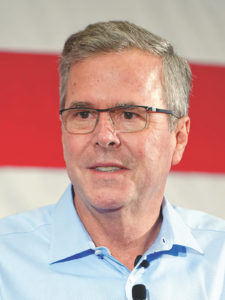

The second generation of Howlands consisted of 88 grandchildren; now, there are an estimated two to two-and-a-half million Howland descendants roaming the planet. Ever wondered what Alec Baldwin, Humphrey Bogart, George H.W. Bush (as well as Jeb and W., of course), Sarah Palin, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Mary Chapin Carpenter have in common? It’s Howland blood. Mayflower descendants all, but not — and least not until later generations — the ones you read about in school.