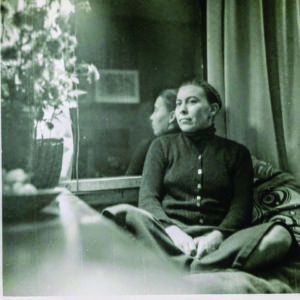

The artist Janet Ann Doub Erickson died at her home on Duck Creek in Wellfleet on Sept. 3, 2021. She was 97. Her death was confirmed by her son Andrew.

She departed life as she lived, with ink on her hands. She made her earliest drawings in Boonsboro, Md., where she was born to a farming family in 1924. As a child, she heard her grandmother describe fleeing Confederate soldiers robbing her pacifist family during the Battle of Antietam. Janet’s mother was a Yankee, and during the Depression her parents returned to her mother’s home in New England.

In 1947, after graduating from the Mass. College of Art and Design, Janet founded the Blockhouse of Boston, an arts cooperative. National recognition followed. When she closed the Blockhouse in 1955, her work had been exhibited in Europe and Israel. A Life magazine profile by Gjon Mili dubbed her “Jumping Janet” for her unique style of stomping on linocuts to ink textiles.

Janet’s long association with Wellfleet began while she was at MassArt, as she slipped away to spend working weekends with her friend Florence Rich, another textile artist, at Florence’s home on Duck Creek. Over the years, Duck Creek evolved from haven to home.

At 32, she won a fellowship that liberated her financially for a few years. Pregnant and unmarried, she drove from Boston with the love of her life, Evarts “Eric” Erickson, to Mexico, frequently stopping along the way to sketch. In Oaxaca, she had a first son out of wedlock, scandalizing her parents. Over the years she had four more children.

For a time, she lived with Eric and her growing family in Guadalajara and Mexico City, interrupted by a brief appointment at SUNY Buffalo. She returned to New England but grew frustrated with its social constraints and winters. She, Eric, and the children relocated to a rambling Mexican-style house in Oakland, Calif., with a studio overlooking citruses and Hawaiian tree ferns.

For Janet, craft was as important as creativity. Her fingers never stopped. She built her own loom, furniture, and fences. She wrote on diverse themes, from ethnic weaving to architecture, and one of her three books, about block printing, remains a classic today. She designed and sewed her own clothing, knitted, did macrame, block-printed, etched, and taught. She sought to ignite her children’s passions, tirelessly exposing them to ideas, music, and science. No museum was safe from their visits. Their birthday parties were legendary. She always made a piñata and devised elaborate games. She built a darkroom for her son Joel and kept chickens to teach the children farming despite neighbors’ complaints about the roosters.

Janet and Eric grew frustrated with American society in the 1970s and left for Europe, eventually settling on the isolated Dalmatian island of Brač in Communist Yugoslavia. Eric worked in the Middle East, supporting the family from afar, while Janet cut firewood, bartered for fish, learned to make olive oil and wine, and wrote poetry, journals, and daily letters to friends. She fended off security officials puzzled by the family’s bizarre residence, home-schooled her children, and explored the western Balkans: hiking Brač’s karst, and traveling by ship, bus, and rail through Yugoslavia, Greece, and Italy, sometimes with Florence Rich.

When it was time to move on, she packed a son off to boarding school in Vatican City and another to a communist finishing school in Belgrade (“It will be an interesting experience,” she allowed, and it was). She moved for a time with daughter Eva to Venice, sketching tirelessly from their Dorsoduro flat, then wandering anew with Eric, visiting far-flung corners of Europe and exploring Asia. They eventually returned to St. Johnsbury, Vt., where son Lars finished high school. Later, she followed family members to Kenya, the Seychelles, France, the Pacific Northwest, and Hawaii, always returning to Wellfleet, where she volunteered in the community wherever she felt she could make a contribution.

Janet found joy in family, art, and mentoring innumerable creatives. She was passionate about making America a better place and an avid correspondent. Her life partner of more than 60 years, Eric, died in Wellfleet in 2019. Her children, Joel, Sara, Eva, Andrew and wife Joanna, and Lars, all survive her, as do nieces, nephews, and grandchildren: Sean and wife Miriam; Alexandra and husband Jon; Rebecca; Astrid; Sophia; Nils; and Nathaniel; and step-granddaughter Zoe Miller. Janet asked that her funeral be celebrated as a fiesta with survivors smiling at the fickleness of fate. Her family is wondering how to honor this wish during Covid.

In the preface to a 1974 edition of one of her books, an arts educator noted that “more than anyone else in America today, Janet Doub Erickson … lifted a craft that had become dull, dead, and dated to a position where we can see its challenging possibilities in the creative renaissance we are now experiencing. Literally with her bare feet, she has brought to Block Printing on Textiles a new dynamic.”

Janet’s children and friends will not forget her tireless spirit and fury to create things new and good. Battling dementia in the second half of her ninth decade, bedridden and struggling to speak, still Janet drew, all day long. The themes changed. Once, she had drawn bold, multi-colored images of the world around her, or extraordinarily detailed representations of architecture and nature. In her final years, when words became challenging, she continued to interpret the world and her own mind with pen to paper.

“There is no such thing as a boring place,” Janet said when one of her children complained of having nothing to do. “There are only boring people. Don’t be one of them.”