Jane Rosenberg would probably rather not be talking to yet another reporter.

“It’s been a lot of interviews since the Trump arraignment,” she told the Independent.

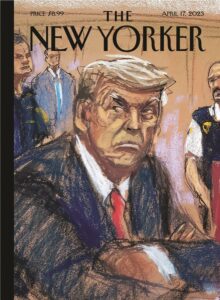

As a courtroom sketch artist, Rosenberg has spent more than four decades behind closed doors capturing the drama of the justice system. But since her “Courtroom Sketch, Manhattan Criminal Courthouse” — a portrait of former President Donald Trump at his New York arraignment on April 4 — landed on the cover of the New Yorker’s April 17 issue, Rosenberg has been warily riding a wave of personal fame. (It was the first courtroom sketch to appear on the magazine’s cover in its 98-year history.)

This is not the court illustrator’s first brush with notoriety or with an astronomically high-profile case; Rosenberg has sketched characters as infamous as Ghislaine Maxwell and as beloved as Tom Brady. But the Trump arraignment was unlike anything else she’s experienced.

“This was the most stressful case I’ve ever done,” she said, adding that she was “so happy” to go back to court on April 14 for a more ordinary white-collar criminal sentencing. (The defendant was James Zhong, who was accused of Bitcoin fraud.) “It was a little business story,” she said of Zhong’s sentencing. “It was just a pleasure. I was the only artist there. It was the opposite of what I had just gone through with Trump.”

Rosenberg tries to avoid any kind of hullabaloo. “I don’t do social media, so I found out from other people that it was going viral,” she said of her Trump sketch. Someone told her the sketch had 3.3 million views on Twitter, but that meant nothing to her. “I’m happy people have a lot of spare time to do social media,” she said. “But I don’t. Everybody likes to be an art critic, but I’m my own worst critic.”

Indeed, despite four decades in the business, Rosenberg still picks apart every sketch she files. In the past, she had until the five o’clock evening news to finish a sketch before the TV outlets picked it up. But in today’s nonstop news cycle, her work immediately goes out of the courtroom and into the world. She compares herself to a professional athlete who is hot on some days and cold on others.

“I always look at it the next day with a fresh eye and go, ‘Oh god, why didn’t I fix this? Why did I put that stroke there?’ ” she said. Sometimes, she goes back and fiddles with the image on her phone using a stylus, but that’s just for her own peace of mind as an artist.

Rosenberg’s interest in portraiture dates to her student days at SUNY Buffalo and later at the Art Students League in New York, and as a “struggling, starving artist for many years” in New York and Provincetown. When she was in college, abstract art by De Kooning, Pollock, and Rothko was modish, while figurative art was passé. “I was a closet portrait artist,” she said. “I’d be home drawing self-portraits in the mirror.”

Throughout the 1970s, Rosenberg trekked to Provincetown every summer and made portraits for five dollars on the street as onlookers peered over her shoulder. She eventually set up a brick-and-mortar portrait shop with other artists, including Simie Maryles, who went on to start a gallery on Commercial Street that now exhibits Rosenberg’s plein air oil paintings.

When she grew tired of the itinerant seasonal lifestyle and began looking for “a way to earn a living in one place,” Rosenberg heard a lecture by a courtroom sketch artist and started a new career. She asked some lawyer friends to bring her to night court at the Manhattan Criminal Court building. Rosenberg’s first big break was the infamous “Murder at the Met” trial in 1981, in which stagehand Craig Crimmins was convicted of throwing violinist Helen Hagnes Mintiks down an airshaft at the Metropolitan Opera. After making her sketch, Rosenberg went home, made some calls, and was summoned to 30 Rockefeller Plaza by NBC. They shot the sketch on film and put it on television that night. “I called my parents,” she said. “I was really excited.”

After a stint as a backup sketch artist for NBC, Rosenberg moved to the first-string position at CBS. But she freelances now, per the industry norm, as not every media outlet still sends its own artist to cover high-profile trials. The job is sporadic, subject to the ebbs and flows of breaking judicial news. Rosenberg has had some lean years. But it’s been unusually busy recently, and she hasn’t had much time to devote to oil painting.

“I’m struggling to find the time — as I’m on the phone with you, talking,” she said, perhaps only half joking.

In her paintings, Rosenberg is drawn to the human moments that also animate her courtroom sketches. “I don’t just want to paint trees by themselves,” she said. “I love painting some kind of emotional content, maybe a solitary moment, walking on a rainy night, or hanging out a window, clapping for the 7 p.m. workers.” That 7 p.m. ritual, one of the fondest collective memories for many of us who were in New York City during the early days of the pandemic, became the basis for some of the last batch of paintings Rosenberg sent to be displayed in Provincetown.

Rosenberg has shifted away from painting cityscapes since 2020, due in part to heightened anxiety about focusing on a canvas instead of watching her surroundings on city streets. “I’ve had incidents with plein air painting,” she said. “There are pervs out there. You have to be careful.”

For now, though, a busy courtroom schedule provides more than enough opportunity for Rosenberg to capture a different aspect of human experience in two dimensions. “I hope for an emotional moment,” she said. “But if there isn’t any, I have to capture somebody doing nothing, just sitting there like a lump. It’s not that exciting, but that’s what my job is: part journalist, part artist, to capture what’s actually going on.”

Her approach has changed over the years. “I’d say the first 10 years, I had a knot in my stomach every time I went to court,” said Rosenberg. “It was terrifying. But as the years went on, I realized; well, I’m going to go on to the next one. I try my best.”

Then, as now, Rosenberg has only as much time to sketch in court as the defendant has to appear. At the arraignment of Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev in 2015, for example, she had just seven minutes. “Sometimes, the pressure is so great that I don’t hear anything,” she said. “I just keep madly drawing.”

Despite her avoidance of social media, Rosenberg knows some people have said she “editorialized” Trump’s expression in the now-famous arraignment sketch, especially compared to photographs where his face was more neutral. But she noted that the photographers had to leave after the first minute of the arraignment, and as the nearly hour-long proceeding dragged on, “he started looking over at the prosecutor and glowering, and that’s what happened.” Keeping an impartial perspective is important to her. “If he was grinning, I would’ve drawn that,” said Rosenberg. “I drew what I saw. It wasn’t based on my political views, although a lot of people like to say that.”

If anything, she said, Trump held that frowning face for longer than she usually has to capture a certain expression — “not ten minutes straight,” she admitted — but “it was a long enough look that I had enough time to do it.

“I was very excited by that, and I thank him,” she said.