PROVINCETOWN — In January 1868, during the heyday of Provincetown’s whaling era, the Barnstable Patriot noted in a small item, halfway down column two on page two, that four whaling vessels, commanded by four brothers, had recently sailed from Provincetown. “We do not believe a similar instance is on record,” noted the writer.

While it was not unusual — indeed, it was commonplace — for vessels to be crewed with family members, the fact that four brothers, Joseph B., George W., James S., and William H. Dyer, were all commanding separate schooners, setting sail from Provincetown at the same time, seems to have been newsworthy. Making it all the more notable was that a fifth brother, Isaac A. Dyer, had commanded the Ada M. Dyer prior to his brother George taking command in 1868.

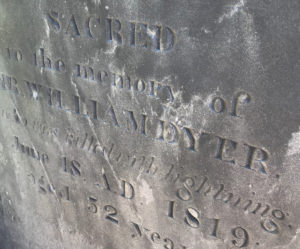

The five Dyer brothers were among the nine children born to James Snow Dyer (1797-1880) and Hannah Cook (1802-1865), who were married in February 1823. James Snow Dyer was the son of William Dyer (1767-1819) and Peggy Snow (1768-1846). Grandfather William’s headstone in Provincetown’s Winthrop Street Cemetery hints at an intriguing story that seems to be told nowhere else: he was “killed with lightning” at the age of 52.

His namesake grandson, William H. Dyer (1823-1909), who commanded the schooner Olive Clark in 1868, was the first born of the nine Dyer children. He is buried in the Dyer family plot in Provincetown’s Cemetery #2, having survived decades at sea. His son, Capt. William Jr., born in 1857, was not as fortunate. At the age of 30 he was lost at sea aboard the schooner Ellen Rizpah during the Aug. 20, 1887 hurricane that swept across the Cape Hatteras whaling grounds.

Tragically, it was not the Dyer family’s only loss during that hurricane. George W. Dyer (1844-1887) was at the helm of the schooner Mary G. Curran in 1887 when it was lost with all hands, a crew of 17. Laden with sperm oil and nearing the end of the voyage, she was last seen sailing in company with another vessel before disappearing in the rain. George W. left a widow and three children. One newspaper noted that he was “one of the most capable whaling captains in this old whaling town.” A family grave in Bucksport, Maine honors his memory.

Some mystery surrounds the life of Joseph B. Dyer, born in 1840. In 1864 he married Hannah Louise Cook and they had three children, two of whom died in infancy. The couple’s firstborn, Artie, died in 1877 at the age of 11 of acute rheumatism. By February 1866, Joseph owned a 1/16 share in the schooner Arthur Clifford, which he commanded — with the exception of the voyage of the A.L. Putnam in 1868 — until September 1870, when the schooner was withdrawn. Though the circumstances of Joseph’s death are unknown and there is no existing grave, on Feb. 27, 1872 Hannah Louise filed for appointment as administratrix of his estate. Joseph’s death must have taken place sometime between September 1870 and February 1872. It seems odd that a family that took such care to memorialize its other members fails to have done so with Joseph.

James Snow Dyer Jr., the second-born of the nine Dyer children, was captain of the schooner Arthur Clifford in 1868, but as a 20-year-old second mate aboard the 100-ton brig Rienzi, he had survived, along with four others from a crew of 21 souls, a harrowing shipwreck. Having departed on a whaling voyage from Provincetown on April 3, 1846, the Rienzi was returning with a full load of sperm oil when, about 1,200 miles east-southeast of Provincetown, it encountered a severe gale late on the evening of Sept. 15. Dismasted and with its hatches burst, the vessel was knocked down and immediately filled with water, drowning six crew members in the cabin. Others drowned in the foc’s’le or were washed overboard before the Rienzi righted itself, a complete wreck.

James Dyer, one of seven crew members from Provincetown, and the only Provincetown survivor, had been in the cabin but somehow managed to find his way to the deck. The five survivors spent 10 days adrift, lashed to the wreck as the sea breached over them, before being rescued from an inevitable death by the ship Minerva sailing from the Mediterranean.

“No pen,” noted news accounts, “can depict the sufferings of the remaining crew. All the provisions they had for 10 days was about half of a peck basket of bread, which they succeeded in getting from the hold, it having been soaked in salt water for 48 hours. The day before they were taken off, they caught a shark by means of a bowline, the liver of which they ate raw; they tried to drink the blood but found it too bitter. All the water they had during their stay on the wreck they caught by putting an old sheet in the rain during a shower and wringing it when it became wet.” The logbook of the Minerva noted that the “poor fellows were mere skeletons, one being delirious, and would have probably died during the night if he had not been relieved.”

In November 1846, the Barnstable Patriot contemplated the “vicissitudes and destroying power of the sea,” writing that those who “commit their lives and property to the perils of the ocean are peculiarly subject to losses and disappointments.” One can’t help but wonder if, as James Dyer went about his life in the years after the Rienzi tragedy, continuing to tempt fate by going to sea, he reflected on the loss of the Rienzi and the six crew members from Provincetown. He died in 1877 and is buried in Provincetown’s Gifford Cemetery, but the Dyer family plot in Cemetery #2 — where “lost at sea” is etched in marble for Capt. William H. Dyer Jr. — is mere steps away from the tomb of the Small family, whose fate was intertwined with that of the Dyers.

James Small was captain and part owner of the Rienzi and his two sons, Joshua, age 21, and James, age 14, were crew members. None survived the wreck. Captain Small’s wife, Betsy, died just months later of a broken heart.