The trap sheds at MacMillan Pier are bright with eight newly installed murals. They’re a Provincetown Public Arts Foundation project that Executive Director Samuel Tager hopes will happen every year.

The artists had no restrictions on the images they produced. For most of them, the location and the large scale, provided an opportunity to experiment with new imagery and techniques.

Samantha Fields, a textile artist who lives in Brockton and has a studio in Boston, is familiar with large-scale work. In 2023, she presented a 40-by-40-foot piece at the Boston Public Art Triennial. Her Provincetown piece, Vibrating Horizon, uses some of the rope from that project. Fields also wanted to incorporate the Provincetown seascape and fishing industry.

Vibrating Horizon expands notions of what a mural can be. It’s composed of rope and buoys hanging from metal bars extending about a foot from the face of the trap shed’s wall. The piece is divided vertically by strips of purple and pink rope, a reference to “that lovely little purple vibrating line between the sky and the ocean” that one occasionally sees on a summer day at the beach, says Fields. She also uses decorative sailing and macramé knots, a nod to this year’s Carnival theme. “You can’t get any campier than macramé,” says Fields.

The duo Kahn & Selesnick, based in New York and France, also chose to forgo working with paint. In a photograph of two men sleeping in a long red rowboat, the pier is a boating space. The photo, shot on the Herring River in Wellfleet, features a man covered in moss.

Yvette Dubinsky, a printmaker working in Truro and St. Louis, made a collage scanned and printed on metal panels for the final piece, Outer / Under Cape. She uses flattened boxes as surfaces for paintings, collages, and prints. In this composition, the painted boxes create an abstract geometric ground. Ephemera from her studio and pieces made specifically for the collage — like a map of Provincetown and wave-like forms — are woven through the composition. The translation to digital introduced rich, saturated color, and the scanning process left surprising, spatially disorientating shadows under objects that weren’t completely glued to the surface.

“The thing with a mural is you want people to understand how it ties into the town and the community,” says Joe Diggs, who also has exhibitions this summer at Provincetown Art Association and Museum and Berta Walker Gallery. He sees his trap shed mural as a response to homophobia and rising hate, and he feels its relevance even more acutely after recent hate crimes in town.

Diggs began with a photograph he took of the water at sunset at Herring Cove. The image is a close-up with the Sun streaking across the surface like ribbons of fire. Watching the sunset, Diggs was listening to the album Waiting Game by drummer Terri Lyne Carrington + Social Science. Back in his Osterville studio with the panels, Diggs began working with markers, writing lyrics from one of the album’s songs on the photograph, following the lines of water with the repeated phrase “pray the hate away.” Four bubble-like forms rise in the center of the composition with additional words. The repeated phrases and the buoyant and glistening imagery conjure a sense of the sacred.

Sky Power of Provincetown painted We the People, displayed outside the harbormaster’s office. Like Diggs’s work, this is a meditation on the relationship between form and content. She worked with an abstract shape composed of eight squares below a rectangle. The shape has appeared in her earlier work, but here she integrates it in a personal and site-specific image: a pink dunescape. A representation of the Constitution — an echo of the abstract form it is paired with — is adjacent.

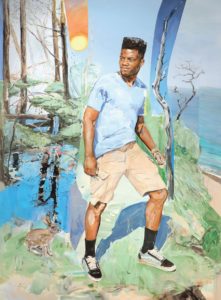

For many of the artists, working on aluminum and at such a large scale was new territory. Naya Bricher, Jerome Greene, and James Everett Stanley are all oil painters who typically work on more modest-size surfaces. They executed their murals over two weeks in studios at the Fine Arts Work Center, where Greene and Bricher currently work and where Stanley was a fellow and is a current member of the board.

Bricher had never worked at this scale before, but her technique of projecting images onto surfaces suited the project. She used a color-matching service to find colors that matched her study. Her painting — featuring desserts, an oversize rose, and an idyllic scene of Herring Cove — captures the pleasure-seeking of Provincetown in the summer.

Greene’s mural depicts Captain Jack’s Wharf on Provincetown’s West End, a subject he has painted before from direct observation. Here, in place of a singular scene, Greene interrupts the image with 10 drawings that appear like spreads from his sketchbook. He made the drawings of musicians, muses, and mentors with paint markers, a new material for him. The composition integrates his drawing and painting practice and reflects both Provincetown’s landscape and its community of creative people.

Stanley also explores personal connection in his mural, Sisters. In the image, his two daughters kneel at the base of a dune looking out to sea, which Stanley paints as a collage-like amalgamation of different times of day and weather.

“Instead of thinking of this as a mural where you scale up your imagery to meet demand, I thought of it as just a really large painting,” he says. The size encouraged him to use bigger brushes and a lively range of painterly touches from large, sweeping gestures to detailed marks.

The image of his daughters is symbolic of his family’s upcoming move from the Outer Cape at the end of the summer and resonates with the other murals, all expressions of a connection to place. In Sisters, the girls “looking at the horizon is specific to this moment,” says Stanley. “It will be the first time they’ll live any place aside from the Cape, so I wanted to do an ode to their childhood here.”

Meet the Muralists

The event: Reception for MacMillan Pier public artists

The time: Thursday, Aug. 14, 6 p.m.

The place: MacMillan Pier, Provincetown

The cost: Free