“This isn’t new to me, and I’m tired of it,” says painter Joseph Diggs, a Cape Cod native. He’s referring to the recent killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Diggs does not have many words to describe his rage and grief, not because he is afraid of confronting these paired emotions, but because he does so through his paintings and has been doing it for a long time.

In 1998, Diggs saw a photo in a newspaper of James Byrd Jr., who had been murdered by white supremacists in Jasper, Texas. “When I read the article and saw the picture, Byrd’s body was chalk-lined, but since he was dragged to death, his body pieces were scattered all over the road,” Diggs says. “So, the chalk lines were little circles around all of his body pieces. I saw them through my tears, and I started drawing their shapes.”

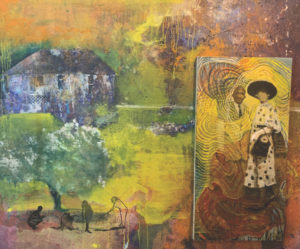

The work that emerged is titled James Byrd Jr., an American Tragedy, and its circular shapes are a recurring feature in most of Diggs’s paintings, including the abstract piece Quiet Souls, part of an exhibit of his work at Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown through July 11.

“I had to find something, because I couldn’t paint James Byrd, Trayvon Martin, and the many others,” Diggs says. “I couldn’t paint all the individual people, because it’s too much. And, quite honestly, I just didn’t want to live in that hell. So, I found this symbol, and the symbol now flows throughout my work.”

He has been impressively prolific: canvases stand stacked against the walls of his large three-room studio space, in his basement, and even along the hallways of his home. During the quiet of the recent Covid-19 lockdown, he arrived at a deeper understanding of the ways in which all his paintings are, in fact, connected.

“It always seemed to me that my work was more fragmented,” he says. “My abstract work went in one direction, my realistic work in another. When I started doing political work, it seemed like they each had their own vein, but at this point they are all tying together. It always felt that way to me, but now I can see it. And it’s exciting.” He adds that his newer work “is more open as a result of more open dialogue happening. I was alone and boxed in 25-plus years ago, due to the lack of concern.”

Diggs’s circular symbols, or “portals,” as he calls them, have also come to stand in a more universal way for loss, grief, and those “souls” who are no longer alive, including many close family members he has lost, some at a young age and tragically. Remarkably, although Diggs confronts and processes painful emotions in his paintings, they don’t focus on darkness.

In his large studio, light streams through tall windows overlooking the vast property by Micah’s Pond in Osterville that he took over from his grandfather. And it is by way of light shining through this landscape that he loves more than any other that the inspiration for Diggs’s paintings arrives.

Over and over again, the shapes and colors he finds within the familiar spaces that surround him — the background of tall trees, the surface of the pond, the clearing that his home and the scatter of cottages stand on, and, down the road, Joe’s Twin Villa, the bar and jazz club that he owned and operated for many years — are echoed in his paintings, whether the expression is abstract or representational. Often, he incorporates old photographs in his paintings to blend the past with the present, “layering them to show the future,” he says. Diggs’s work, which he describes as being “most importantly connected to my soul,” has become his form of remembrance, of honoring the past, of “bringing old back to new and trying to push forward history.

“I’m just trying to get stuff out,” he continues. “Trying not to keep it in and trying not to be overly angry, because I’m not overly angry — sitting out here in the woods almost makes it so I can’t be.” Diggs smiles. “I wonder, sometimes, how much of an oddball I am, you know, sitting out here without any connection with other artists.”

Connection and community are things that Diggs has come to long for more and more. He has a dream of creating a residency for young artists of color on his property. “These cottages were built for people of color,” he says. “And they used to come here in the summertime. Now, of course, as the economy changes — especially for people of color — they have stopped coming.” Diggs explains that Airbnb rentals in the affluent neighborhoods surrounding his have taken over the market and left his simple summer rental compound empty. In a similar way, Joe’s Twin Villa — once a popular destination featured in the Negro Motorist Green Book — is now defunct, after new town regulations led to the need for costly and unfeasible upgrades. “It was just a way to weed people like us out,” he says. “And that’s exactly what they did.”

Characteristically, Diggs is trying to see this as a potential way to build upon history, instead of merely as a loss. “What I would like to see is a spot for artists of color to know that they have a place where they will be accepted and their work will be accepted,” he says. Here on Cape Cod, he adds, that kind of place is sorely needed.

Up From Osterville

The event: Paintings by Joseph Diggs, on view as part of an exhibit with work by Deb Mell and Lucy Clark

The time: Through Saturday, July 11

The place: Berta Walker Gallery, 208 Bradford St., Provincetown; gallery open by appointment only: calendly.com/bertawalker

The cost: Free