PROVINCETOWN — Every spring, the Outer Cape’s population, and payrolls, swell, as about 5,000 people pick up seasonal jobs here, according to Cape Cod Commission data. Some of those 5,000 live here year-round and pick up their summer work in March or April. Others arrive from places like New York, Boston, or Florida around May 15 — the traditional start date for the increasingly rare summer rental.

About a quarter of those 5,000 workers normally arrive from overseas, through a pair of “non-immigrant visa programs” called J-1 and H-2B. The J-1 Summer Work-Travel program brings about 700 college students to the four Outer Cape towns in a normal year, mostly from Bulgaria but also from other East European countries. The H-2B program brings another 700 or so adult workers, mostly from Jamaica.

But this is not a normal year.

For the three-quarters of the workforce who are American, the greatest challenge by far is finding a decent place to sleep at night, as the stock of year-round and seasonal rentals has been eroded by the growth of the short-term rental market.

For the quarter who come from overseas, the greatest challenge this year is getting a U.S. embassy to process a visa. President Trump’s “visa ban,” initiated by executive order on June 22 and extended on Dec. 31 of last year, then left by the Biden administration to expire this March 31, has effectively killed the J-1 program in many countries this year, and severely limited it in others.

The J-1 short-circuit and lack of affordable housing are combining to bring the local economy to what state Sen. Julian Cyr and Cape Cod Chamber of Commerce CEO Wendy Northcross are both calling a crisis point.

The H-2B program is in better shape, partly because certain U.S. embassies and consulates continued to issue thousands of H-2Bs visas even while the ban was in effect. This appears to have been due to a loophole that allowed H-2B workers providing “labor or services essential to the United States food supply chain” to receive visas.

In the six weeks since the ban expired, the J-1 program has come back to life, but slowly. At U.S. embassies overseas, where Covid protocols have limited the number of staff allowed at work, the thousands of visa interviews that would otherwise have been underway since early spring now currently number in the tens or low hundreds, depending on the location.

The State Dept. will not answer questions about visa production overseas, and individual embassies refer questions back to Washington, D.C. But posted State Dept. records and conversations with visa operators help paint a picture of how visa production is really going now.

“The 26th of April was the first day of J-1 visa interviews in the embassy,” said Antoni Slavimirov, co-owner of the Agency for International Mobility in Sofia, Bulgaria, which recruits college students into the J-1 program. “They were doing five interviews per day,” he said. “Now they are doing 10 per day.” That makes 50 visa interviews in a week, in an embassy that used to do many hundreds per week.

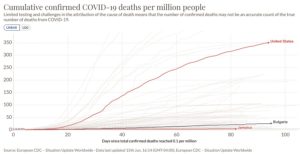

In 2019, Bulgaria sent almost 5,000 J-1 students to the U.S., according to State Dept. records. At the current pace, that number might not reach 500. The rest of Bulgaria reopened at the end of April, Slavimirov said, making the point that it’s not the country but the U.S. embassy that’s the bottleneck.

This problem is not limited to Bulgaria. Turkey sent 11,000 J-1 students to the U.S. in 2019, but the U.S. embassy there announced it won’t be scheduling any J-1 interviews this year. The U.S. embassy in Russia usually sends 7,000 student workers to the U.S., but they’re embroiled in a diplomatic dispute with Putin’s government, and won’t be doing any J-1 interviews now.

There are embassies in the region that appear to be more active, including those in Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine. According to the State Dept.’s J-1 visa map, there are now about 250 students currently pursuing visas for work in the four outermost towns of Cape Cod. That’s less than half the normal number, but it still means the sounds of Bulgarian, Serbian, and Romanian might be heard here by summer.

When it comes to the H-2B program, the Outer Cape may stand a better chance of getting its normal number of workers this year. That’s because the U.S. Embassy in Kingston, Jamaica has been aided by two forces — the “national interest exception” that exempted food supply chain workers from the visa ban, and rules that allow many returning workers to have their interview requirements waived.

State Dept. records show that the embassy in Kingston issued 2,700 H-2B visas between October and March, in spite of the ban — about half its normal rate.

One twist in the story of the slowdown is that local employers actually asked for slightly fewer H-2Bs this year than in prior years. Normally, employers in the four Outer Cape towns apply for — and are certified for — about 700 positions in a season, principally housekeepers and cooks. This year there were only 562 certified H-2B jobs in the four towns.

The process employers go through is complex and uncertain. First, certification involves proving to the Dept. of Labor that positions were properly advertised to Americans, with a published wage rate based on prevailing wages, and could not be filled. H-2B workers must be paid the prevailing rates that were advertised. The average starting hourly wage in the 37 applications from Provincetown this year was $15.32.

Even if all the employers’ applications are certified, it’s still hard to know how many H-2B workers will arrive. After certification, the applications for workers are then run through a nationwide lottery system until a summertime cap of 33,000 workers is reached. In most recent years, that cap has been altered or lifted; this year it was raised by a further 22,000. The date of the second lottery for those 22,000 visa spots has not been announced yet.

The uncertainty of a lottery system is an aggravation for employers and workers alike, and Cape Cod’s U.S. Rep. Bill Keating wants the lottery scrapped entirely.

Unlike J-1 students, who are no longer eligible for the program once they’ve graduated from college, many H-2B workers have been traveling from Jamaica to the Outer Cape and back for years or even decades.

Yet there are plenty of Outer Cape employers who still don’t know if they’ll get their H-2B workers.

In the meantime, an optimistic tally of 500 H-2Bs and 250 J-1s would mean about 700 workers fewer than those normally here for the season.