On a colder-than-usual December Thursday, Isabelle Quinn roams the dunes of Wellfleet’s Newcomb Hollow Beach in search of driftwood. The wind nips at her, turning her knuckles purple, but Quinn persists. “I’m looking for wood that’s already lived a life,” she says, “pieces that represent the choreography of nature.”

Each piece of wood tells its own story, revealed through its distinct shape and grain, she says. In her hands, these old, battered branches and panels begin their next chapters.

Quinn specializes in seaside landscapes painted on found materials, mainly driftwood from Cape Cod beaches. She’s found the biggest planks, ones long ago broken from ships, on the outermost beaches, she says. Those she prizes because they mean a more expansive surface for her to paint. Quinn’s art practice is deeply entwined with the beaches here, she says: “These are the coastlines I’ve cherished my entire life.”

The 24-year-old spent her childhood summers on Cape Cod with her family. But it was a visit in 2018 that marked a serendipitous turning point in her creative life. While wandering the Brewster flats, Quinn found an old wooden plank, weathered and beaten; intrigued, she took it home. “I was mesmerized by the texture of the wood,” she says. “I wanted to try to paint a landscape into the grain of it.”

In 2021, after graduating from UMass Amherst, Quinn started a new job at Expressions Gallery in Chatham and moved to Brewster. “That summer, I embraced a ‘wander, collect, notice, create’ mantra and started painting a lot more,” she says. She fell into a rhythm: she gathered driftwood from beaches and, after work, set up a folding table in her back yard to paint into the night. A few months later, Quinn had her first show at the Harwich Cultural Center art fair.

At a picnic table outside the Wellfleet cottage she calls the “driftshop,” Quinn sands a piece of driftwood, the canvas for her next painting. As she works, smoothing out the coarse edges and shards, she nicks a finger on a wooden shard. “I constantly have splinters,” she says.

Next, she grabs a toothbrush to clean out the sand trapped in the wood’s grain. She hammers hardware to the back of the now-smooth slab, then, holding the wood at both ends, lifts it to eye level, checking that it will hang evenly. “Yep, it’s good,” she confirms. When you’re working on driftwood, she says, “You have to take care of your canvas.”

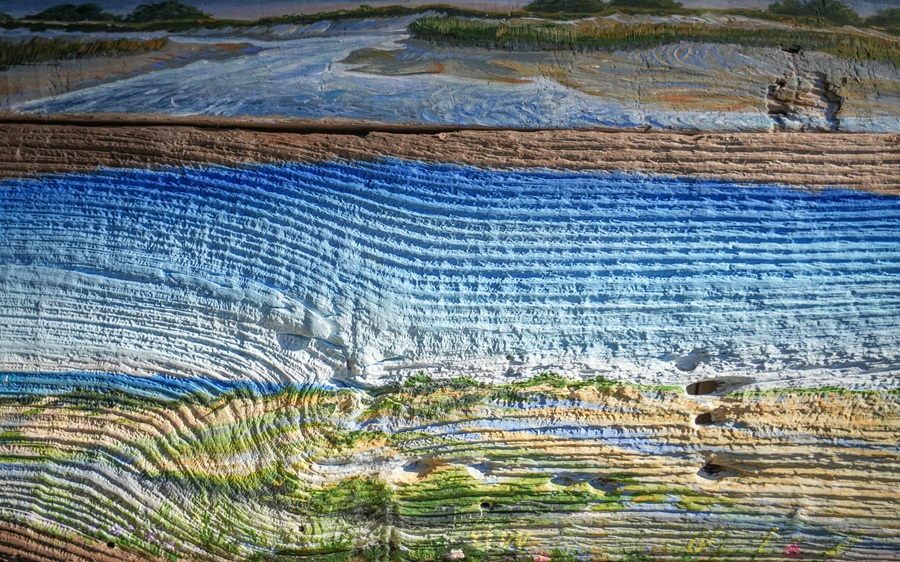

Inside, Quinn sets up her painting station at a folding table in the kitchen. Afternoon sunlight comes through the window. She leans forward and applies a base coat to the driftwood canvas; it’s always white acrylic paint or gesso, depending on the wood’s texture. Next, the sky. Using gesso paint and a thick brush, she paints a blue horizon, then, with thinner, pencil-like brushes and a palette of earthy tones, she adds details to her landscape: blades of grass, wildflowers, and rocks take shape.

Between paint strokes, Quinn dabs her brushes on her shoulder to wipe away excess paint, inadvertently creating an abstract painting on her clothing. “I have to sacrifice a lot of clothes,” she says.

Quinn’s signature includes a crescent moon: small, faint, and in the corner of every one of her paintings, even the ones set during the day. It’s an ode, she says, to the gravitational force that controls the tides that bring her the wooden canvases. After the paint dries on the driftwood slab, Quinn grabs a tiny brush and gently applies the crescent with white paint. Then she signs her name.

On the back porch are stacks of collected driftwood waiting for Quinn’s attention. She reaches for a particularly lanky piece, the longest and thinnest in the pile. “It’s tree bark that split off beautifully,” Quinn says, musing over it, envisioning the landscape she will bring to life on its surface.