In the early 1900s, a slaughter took place every fall in the mountains above Drehersville, Pa. at the foot of Blue Mountain, a ridge of the Appalachians in the eastern part of the state.

Irma Penniman, who grew up in Eastham, helped put a stop to it.

Drehersville is on a major flyway for North American birds of prey, including eagles, hawks, and falcons. At Blue Mountain, the flyway narrows, creating a chokepoint for migrating hawks. There, hunters, driven by the misguided belief that hawks were vermin, gathered on the ridge on weekends and gunned down hundreds of raptors every day. This mass killing of raptors went on for decades.

Irma Penniman was the granddaughter of Capt. Edward Penniman. She was born in 1908 in Dorchester, but at age two, following her parents’ divorce, she was brought to Eastham to live with her grandparents and her Aunt Betsey.

Irma wrote lovingly of her grandfather and described sitting on the old sea captain’s lap and combing his beard. Once, she wrote, when some visiting relatives made fun of her frail appearance, her grandfather took her aside and said, “You’re my little tough-brick.” She later wrote that the remark “served me well through many a crisis in my adult life.”

As a child, Irma developed a keen interest in the natural world. A few years after graduating from Orleans High School, she began volunteering at the Austin Ornithological Research Station, where Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary is today. There, she learned to band birds from the station’s young research associate, Maurice Broun.

“I walked up to him and I stuck out my hand and said, ‘Thank you very much,’ ” Irma recalled in an interview with the Allentown Morning Call in 1989, describing the day they met. “And then I said, ‘I think it would be great to marry an ornithologist.’ ”

Maurice Broun, the child of Romanian immigrant parents and orphaned when he was two, made a name for himself working for Massachusetts State Ornithologist Edward Howe Forbush. He wrote about the summer he and Irma met in his 1948 memoir, Hawks Aloft.

“Day after day, in the hot July sun, we combed the Cape Cod beaches, banding tern chicks.… The terns protested, screamed, and dive-bombed our heads, sometimes drawing blood with their stiletto-like beaks. But the slight little lady never protested,” Maurice wrote. “Any young lady who can survive this ordeal was made of heroic stuff.”

“In due time, she herself was banded,” Maurice wrote. “And we lived happily ever after.”

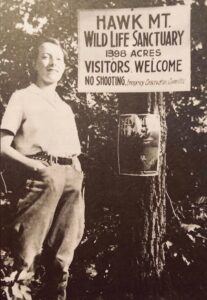

Less than nine months into their marriage, the couple got an offer that changed their lives. Rosalie Barrow Edge, a suffragist, environmentalist, and New York City socialite, had purchased 1,400 acres of land overlooking Drehersville. Edge planned to turn the place where hawk hunters gathered each fall into the world’s first sanctuary for raptors. And she wanted Maurice to be the new warden.

At the time, the idea of protecting birds of prey was deeply controversial, even among conservationists. Raptors were maligned, thought of as killers of livestock and game, although the ecological role they fulfill as predators of rodents is beneficial to agriculture. Hunters were encouraged to shoot them whenever they could. The Pennsylvania Game Commission even introduced a $5 bounty on American goshawks in 1929 — nearly $100 in today’s money. The National Association of Audubon Societies refused to condemn a bald eagle hunt in Alaska in 1917.

Maurice’s job would be to stop the slaughter on the mountain. But game wardens faced real danger at the time: Guy Bradley, a warden in the Everglades, was murdered in 1905 while trying to stop hunters from killing herons. Maurice accepted the job, and he and Irma moved to Drehersville, where Maurice began patrolling the new sanctuary.

Immediately, he was met with resistance. Dozens of hunters tried to enter the sanctuary every weekend. Someone strung up a dead red-tailed hawk over the bridge to the sanctuary. Local hunters persuaded the Pennsylvania State Police to investigate the couple by claiming that they were Nazi collaborators. The subsequent investigation found no evidence of collaboration.

But soon, things became more violent. A group of drunk, armed men showed up in the night and forced the landlord to evict the couple from their house. One of the men told them, “You’d better leave the mountain soon or we might have to shoot you off.” The local game warden and state police refused to help them — they were all hawk hunters, too.

Despite the threats, Maurice and Irma stayed in town, and the violence failed to materialize. After the first year, Rosalie Edge decided that the sanctuary needed a dedicated hawk counter and she wanted Maurice to do it. This would leave Irma as the sanctuary’s warden. Maurice had some misgivings, but Irma insisted she wanted to take on the job.

It did not take long for Irma to become known as the “keeper of the gate,” welcoming visitors in to enjoy the raptors and keeping hunters away. In a 1993 interview she told the Stanislaus County Library “bullets shot over our heads,” and angry hunters told them to “get off the mountain or we would be sorry.”

One incident in particular stood out to her: She was guarding the gate when a man pulled up in his car with a gun and two hunting dogs. She called to him, “There’s no hunting in there, you can’t go in with your gun and dogs.”

“Who’s going to stop me?” he asked.

“I am,” she said. He laughed at her.

“I have a gun and I know how to use it,” she called back.

The hunter gave her a look, then gathered his dogs, got back in his car, and drove off. “There must have been fire in my wife’s eyes, and steel in her words,” Maurice wrote of the incident.

Irma later admitted that she had been bluffing. She told the Morning Call that she didn’t have her gun on her at the time — “But I did know how to use one,” she said.

Irma encouraged the hunters to go and observe the raptor migration (without their guns). Maurice’s autobiography includes many accounts of locals arriving at the mountain hoping to shoot hawks and leaving with a new love of these birds.

Soon, as many as 850 people visited Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in a day. Irma greeted them all. “She is wholly devoted to the project in hand,” a reporter for the Morning Call wrote. “Irma Broun knows all the answers.” Local opposition faded, too, as the influx of tourists made Hawk Mountain into a point of local pride, according to Maurice’s writings.

Maurice and Irma’s work made a difference beyond the sanctuary. In 1937, the Pennsylvania Game Commission acknowledged “much good has been accomplished through the establishment of the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary” and banned hunting of all but three raptor species — the most maligned sharp-shinned hawk, Cooper’s hawk, and American goshawk. The Brouns did not consider this adequate, but it was progress, Maurice wrote.

In 1940, the Bald Eagle Protection Act was passed, making the killing of these birds a federal crime. Elsewhere, other hawkwatches began to spring up, first in New Jersey, then New York.

But six years into the sanctuary’s existence, a new threat to raptors emerged: the pesticide Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT. The compound was used as an insecticide in World War II, with the idea that it would limit the spread of malaria and typhus, and by 1945 was being promoted to farmers and for home use by industry and the government — and widely adopted.

No one knew it at the time, but DDT was making the eggshells of larger birds brittle. Eggs were being accidentally crushed in nests before they could hatch, causing a massive decline in many species, including bald eagles and peregrine falcons. Within two decades, Maurice’s data showed that the numbers of these two species had dropped to a third of what they had been before DDT was introduced.

With that data, the Brouns would save their beloved raptors a second time. When Rachel Carson was writing her groundbreaking book, Silent Spring, she relied on Hawk Mountain’s data to show that DDT was causing raptor declines — it was the only data set that was old enough to show a clear before-and-after picture of raptor populations with respect to DDT.

When Silent Spring came out in 1962, it caused a nationwide uproar and led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and the banning of DDT in 1972, after which raptor populations rebounded quickly. In 1963, there were fewer than 500 nesting pairs of bald eagles across the entire lower 48 states. Today, there are around 72,000.

Maurice and Irma spent every fall migration living atop Hawk Mountain. “Maurice and I were so close we didn’t feel the need for anyone else,” Irma said. When they retired in 1966, they moved into a house near the sanctuary.

Maurice died in 1972. In the months following his death, Irma and Maurice’s good friend Richard Kahn, who had been best man at their wedding, became close. They married and moved to Modesto, Calif., with Irma returning to Hawk Mountain only occasionally to give lectures about her experience there. When she died in 1997, she was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Eastham. The house she grew up in is the Penniman House, a National Historic Site owned and cared for by the Cape Cod National Seashore.

Today, killing raptors is illegal across the country, and raptor populations have recovered dramatically. There are more than 200 dedicated hawkwatches across North America, all modeled after Hawk Mountain’s. Moreover, raptors have gone from being viewed as pests to being understood as a crucial part of a vibrant ecosystem.

Maurice wrote in his autobiography, “I make a bow to my wife Irma, the keeper of the gate.”