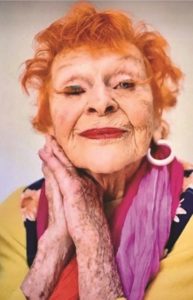

Zoë Lewis recalled the first time they met. “It must have been 1998, or maybe 1997,” she said. A woman under five feet tall with flaming red hair, a flamboyantly colorful dress, and eyelashes so long they would have preceded her into a room approached her on Commercial Street. Much to Zoë’s surprise, the woman addressed her by name and said she knew Lewis played the piano. Then she asked, “Will you accompany me?”

“Have you performed before?” Zoë replied, to which the answer was no. “But,” she continued, “I know I can.”

Lewis pressed: “How do you want to perform?”

“Like Marlene Dietrich.”

They planned a show of three songs with three costume changes, which the woman wore on top of each other. During the show, she sat on a tall stool and half talked and half sang, peeling off a layer of costume after each song, while pumping her legs as if performing a can-can.

At the end of the set, she jumped off the stool and danced, finishing with a split. The audience went wild.

That was the beginning of a show called “The Eyelash Cabaret,” performed annually by Ilona Royce Smithkin, accompanied by Zoë Lewis, at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum and in New York.

Ilona died peacefully in her sleep on Aug. 1, 2021 after drinking a little cup of vodka in her third-floor apartment above the Karilon Gallery in Provincetown. She was 101.

A resident of the West Village in New York and of Provincetown, Ilona was an artist who specialized in portraiture; she was also a respected teacher of painting. Later in life she became a model for Ari Seth Cohen’s “Advanced Style” project on fashion for women over 60 and, as noted above, a cabaret singer in her 80s. For Ilona, painting, fashion, and performance were all a seamless part of simply living.

The daughter of Mordka Rosenkranz and Frida (Lubinski) Rosenkranz, Ilona was born on March 27, 1920 in Poland. A year later, the family moved to Berlin before fleeing in 1938 to escape the Nazis. With the family name changed to Royce, they settled in New York. In 1939, Ilona married Irving Smithkin, who was killed in World War II.

When asked about her childhood in the short film Ilona Upstairs (2012), she explained that, for her, “the past is such a strange thing.” She recalled little, she said, but remembered the rise of Hitler. That memory, she explained, caused her head to shake involuntarily. It was not Parkinson’s, she said, but rather “repressed fear.”

In a WOMR interview recorded when she was 96, Ilona recalled how she had no toys, so “I made my own.” Her father was strict. “Work, work, work, and discipline, a lot of discipline” were the hallmarks of her youth. She credited that early discipline with giving her the strength to become an artist.

Ilona first came to Provincetown by train in 1947. She found a room for $3 a night. By the 1960s, she and Karen Katzel had opened the Karilon Gallery. A third-floor apartment above the gallery became her Provincetown home.

She taught painting for 40 years in Kentucky and South Carolina. In 1975, the South Carolina public television network broadcast 40 half-hour painting classes called “Ilona’s Palette.” “Painting with Ilona” followed in 1983. The shows were followed by the publication of two books: Painting With Ilona and Finishing Touches With Ilona. Back in Kentucky she was given the unlikely honor of being named a “Kentucky Colonel” for her work in small towns and villages throughout the state.

In New York and Provincetown, Ilona worked on portraits, often of well-known figures like Tennessee Williams and Ayn Rand. She painted in a restrained style, highlighting parts of the face to indicate a larger, unseen whole. Rand said she admired how Ilona deployed “a minimum for a maximum,” an expression Ilona came to adopt to describe her work to others.

It was not until she was well into her 80s that Ilona suddenly found herself not just respected in the art world but famous all over the world. With the release of the documentary Advanced Style in 2014, the public visibility she had achieved through her cabaret show expanded exponentially across the globe. It also resulted in a third book, Joy Dust, Ilona at 96 (2016).

Ilona remained wonderfully modest and irrepressible. “Happy with the person I’ve become,” as she put it to WOMR, Ilona reflected on how she had come to understand not just her life, but life. She had to, she said, “get rid of me,” stop looking for approval, and stop fearing judgment.

Such insights informed her teaching in her later years. Christine McCarthy, director of PAAM since 2001, described how Ilona began her painting classes every year with a “small bouquet of flowers.” Zoë Lewis said that if a student, to use Ilona’s expression, “did a boo boo” on a painting, she would give the student a kiss, saying “boo boos are opportunities to learn.”

In the last weeks of Ilona’s life, Lewis spent every Saturday morning with her. Their talk ranged over art, music, and performance. “She just saw paintings everywhere,” Lewis said. “She loved color, she had an artist’s eye, and she painted the way she did fashion.”

She also “dreamed songs, shows, and films; she had them all in her mind.” She sang songs Lewis had not heard before, sprinkling “joy dust” on the audience as she had done in her cabaret act.

“We all want to be loved, and she loved everyone,” said Lewis. “She was really present. She could hypnotize with her eyelashes!”