Just before Carmen Maria Machado left for graduate school, she came down with swine flu. The year was 2009: Barack Obama had just started his first term as president, Bitcoin had recently launched as the first decentralized cryptocurrency, and Netflix’s online streams had outpaced its DVD shipments for the first time.

Perhaps more important: “That was right when Netflix introduced autoplay,” Machado says. “So, while I was wracked with fever, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit was playing in the background.”

Years later, while trying to recall the story of an episode she’d seen during that time, Machado found herself looking at one-paragraph summaries of all the show’s episodes online. She says she found those capsule descriptions fascinating, especially as a narrative mode.

In 2013, those summaries became the structural basis for Machado’s novella Especially Heinous. Her story follows SVU protagonists Benson and Stabler as they investigate the various crimes portrayed in the TV series, but there are added elements: murdered women haunt Benson as ghosts with bells for eyes; a pair of too-perfect doppelgangers named Henson and Abler stalk New York’s streets. Near the end of Season 9, Stabler stares into the sky and begs the reader to put down the book.

“It’s a story about crime narratives, binging TV, and how we think about the body, especially marginalized bodies, as a sort of currency,” Machado says. “Women, children, nonwhite: what does it mean that the body is consumed, destroyed, and put on display? That it’s commodified and commercialized for our viewing pleasure?”

Especially Heinous, like much of Machado’s work, defies easy categorization. It’s a detective story, but it’s also a work of horror fiction, science fiction, fantasy fiction, and metafiction. Her oeuvre is wide: she’s written short stories (Her Body and Other Parties), a memoir (In the Dream House), and even a miniseries for DC Comics (The Low, Low Woods). She’s currently working on a set of interconnected stories called A Brief and Fearful Star, which she says is “set in a multiverse where a comet called Solo-9 enters all of space-time simultaneously.”

The connecting thread in Machado’s writing is a fascination with the human body. It might be turning invisible as in Real Women Have Bodies, falling apart as in The Husband Stitch, or being outright destroyed as in Especially Heinous. “I’m interested in the intersection of body horror with the reality of the body,” she says. “The way the body fails us, the way it brings us pleasure, the way it carries us away at the end. The way we are subject to our body’s whims, to this animal that is carrying us around.”

The term “body horror” was coined in 1983 by writer Phillip Brophy to describe the visceral nature of horror films like Alien and The Thing. But Machado says humans have been interested in the degradation of the body for much longer than that: she mentions Christians self-flagellating and eating human flesh for salvation, and 20th-century novelists like Angela Carter and Shirley Jackson using speculative, surreal elements to investigate the role that women’s bodies play in modern society. To her, body horror is “a way of defamiliarizing, of looking at something with fresh eyes,” she says. One way to do that is “to change the genre you’re in.”

Machado is offering a workshop at the Fine Arts Work Center this year called “The Monstrous Body,” taught in parallel with a workshop of the same name led by visual artist Ilana Savdie. The two workshops share more than a name. Machado and Savdie plan to overlap for a day, combining visual and written prompts to examine the instability of the body.

Machado and Savdie first met in 2023 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Savdie had named a painting after Machado’s short story The Husband Stitch, and Machado says the two “connected instantly.” Machado and Savdie both taught at FAWC in 2024, but this will be the first time their workshops physically overlap.

Like Machado, Savdie says she’s drawn to the uncanny: to the sensation of “in-betweenness,” to the place where she says a piece “hovers between familiarity and estrangement, pleasure and disgust, horror and comedy.”

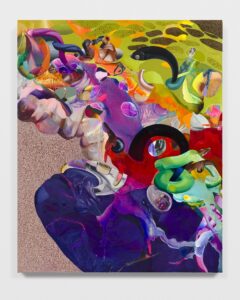

Savdie’s art is vibrant and visceral, with shapes and colors that bleed violently into one another in parodies of biological construction. Ribs seem to burst out of a jawlike structure in Even By a Nation of Devils; a metallic ring holds together what might be flaps of bleeding skin. In Pipa Pipa, something red and purple and octopoid seems to leak golden honey from its writhing tip. The end result is equal parts nauseating and beautiful.

“The body becomes monstrous when it refuses containment,” Savdie says. In her work, she defines monstrous as “a refusal to be whole and an accumulation of pieces at odds with each other.” Her paintings, usually a mix of oil, acrylic, and beeswax, are what she calls “a collision of disparate strategies — repetition, procession, erosion, representation to the point of unravel.” She says she looks to create “contradiction and slippage” in her work.

“I see the monstrous as a radical mode of resistance,” Savdie says. “It’s a way to inhabit contradiction without resolution.”

Savdie, like Machado, says she’s long been interested in the human body and its monstrosity — all of us have bodies, she says, and she’s “a bit suspicious of anyone that isn’t interested in the monstrous.” She says she held jobs in the beauty industry, most notably in photo retouching and the creation of stock photography. The restrictions she faced felt authoritarian. She says the images that were “monstrous, perverse, or contaminated” became gestures of freedom for her.

Much of Machado’s interest in the body’s frailty comes from even earlier, during her childhood. “When I was between 8 and 10 years old,” she says, “I was extremely sick and I didn’t know why. They never figured out what it was.” She recalls visiting hospital after hospital without resolution: this kickstarted a lifelong interest in the mechanics of the human body.

Machado’s work is often identified as queer fiction — both Her Body and Other Parties and In the Dream House won the Lambda Literary Award, the former for lesbian fiction, the latter for nonfiction. Both books also won the Bisexual Book Award — the former for fiction, the latter, once again, for memoir. But Machado says there’s more to her brand of body horror than queerness.

“There’s a lot of metaphors in there,” she says. “I would say you can do a queer reading of that kind of work — for anything about transformation — but it’s not just queerness. It could be chronic illness. It could be disability.”

Nonetheless, Machado says, she “really likes being around lots of queer people” when she visits Provincetown — “It’s just a beautiful place,” she says. It’s the setting of “Eight Bites,” one of the stories in Her Body and Other Parties. She doesn’t identify the town by name, but she says it’s recognizable. It is.

Turning Invisible and Falling Apart

The event: Artist talk and reading with Ilana Savdie and Carmen Maria Machado

The time: Wednesday, June 25, 5 to 7 p.m.

The place: Stanley Kunitz Common Room, Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free