NORTH TRURO — For nearly 150 years, North Truro’s East Harbor was an oxygen-depleted saltwater-turned-freshwater lake, cut off from Cape Cod Bay by a manmade dike. Now, thanks to the water flowing through a single culvert, it is partially reverting to at least one of the things it once was: a home for horseshoe crabs.

The return of horseshoe crabs “is a really good indicator that there is a functioning brackish water ecosystem” in the harbor, said Kelly McCusker, a master’s student at Antioch University. Researchers from the Cape Cod National Seashore, Antioch, and other institutions have been studying East Harbor’s fauna since 2011. In 2022, the Seashore and the university began a project to research East Harbor’s horseshoe crabs, which McCusker joined this year as part of her thesis work.

For most of its history, East Harbor was a salt marsh that was home to a host of ocean animals. After European settlement it became a working harbor, sheltering boats in winter, too. Then, in 1868, the state constructed a dike spanning the harbor to build a railroad bridge to Provincetown. This blocked the harbor’s tidal flow and slowly turned it into a freshwater lake that was oxygen-poor, drove insect outbreaks, and killed fish.

After a particularly devastating die-off in 2001 — an estimated 30,000 fish died for lack of oxygen — the valve on the dike’s one culvert was removed in 2002, allowing salt water to slowly flow back into the harbor through a four-foot-wide hole. It wasn’t long before the first ocean creatures recolonized the harbor, and horseshoe crabs were among them.

McCusker’s goal is to characterize the population of horseshoe crabs that now live in East Harbor to understand how they are using the area. Her team spent the last two summers surveying crabs and affixing white tags to them to identify individuals. Over the last two summers, the team has tagged 833 crabs. They’ve had very few recaptures over the two years: only 7.5 percent of the crabs they found had already been tagged. This indicates that there are significantly more untagged horseshoe crabs using the system, likely well into the thousands, McCusker said.

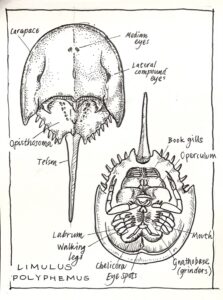

Her team has discovered some of what the horseshoe crabs are doing in East Harbor: they’re mating. Nearly half of the creatures they found were in a horseshoe crab embrace, the smaller males latched onto the backs of females. These interlocked crabs will crawl onto the beach together, where the females will lay eggs in a sandy nest as the males fertilize them. The scene, and the fact that in both summers the researchers have discovered juveniles in the water, suggests breeding adult crabs are finding East Harbor a safe spot to reproduce.

While McCusker says she is still analyzing the data, it appears the horseshoe crabs are using most parts of East Harbor. She has even detected one crab leaving the harbor for Cape Cod Bay via the culvert. This, she says, is “really exciting.”

That’s because while they’re not officially listed as endangered in Massachusetts, horseshoe crab populations in the state are a far cry from their historical numbers. For decades, they were officially listed as a pest animal in Massachusetts.

“They were a shellfish predator to be eliminated,” said Mark Faherty, the science coordinator at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. “You were supposed to just kill them on sight.” Shellfishing license holders were even required to kill horseshoe crabs as part of their license agreements.

Their falling numbers is part of why McCusker’s research in East Harbor is important. This study may provide further evidence of the value of restoring coastal salt marshes, as they are among the few places in the state where horseshoe crab populations are recovering.

Today, Cape Cod’s crabs are harvested as bait for the whelk and eel fisheries, but there is growing pressure from the biomedical industry, too. The horseshoe crabs’ blue blood is extremely sensitive to bacterial infections and can be used to reliably test the sterility of vaccines and medical devices.

“Anything that goes in our bodies gets tested by horseshoe crab blood,” said McCusker.

Collecting this blood, however, kills between 15 and 30 percent of the crabs that are bled.

Conservationists see the crabs as an important part of our tidal habitats. They even act as habitat themselves for the barnacles and other immobile organisms that grow on their bodies. They have also historically fueled the flights of migratory shorebirds, according to Alan Kneidel, a conservation biologist at Manomet Inc. in Plymouth.

For the red knot, a robin-sized shorebird that migrates from as far as southern Chile to northern Canada, horseshoe crab spawns are especially important. This crab’s population decline on the East Coast is part of why the rufa subspecies of red knot has decreased by an estimated 75 percent since 1980.

“You could definitely have an entire graduate research course on horseshoe crabs as a management issue,” said Faherty. “There are so many stakeholders surrounding this ‘sea tick’ that’s been around for 450 million years.”

McCusker feels her findings in East Harbor are a hopeful sign, not just for the crabs themselves but for all the tidal organisms that have recolonized the harbor. During her team’s days in the field, she was struck by the variety of other species that now appear to be thriving in the harbor — bay scallops, oysters, seabirds, and other saltwater organisms seem abundant now, and that diversity is encouraging.

“Even a little bit of restoration,” she said, “can really go a long way.”