PROVINCETOWN — It’s here — you just have to picture it. Imagine it’s midwinter in 1871 and your frozen feet are planted on a sandy stretch of what is now called Herring Cove Beach, south of Hatches Harbor. Facing Race Point, you see 33 modest wooden huts, each with a single window and a stovepipe cut through the roof.

Peering through a smudged window, you see seven or eight Azorean fishermen squeezed inside, sprawled on makeshift beds, working or relaxing by the light of a kerosene lamp as the winter sun sets on the horizon. They are immigrants who evaded Portugal’s eight-year military draft by joining the crews of Massachusetts-bound whaling vessels. One of them is playing a guitar. Others sing along, dealing cards, gambling, and drinking whiskey — something they can’t do openly in town, which will remain dry until 1920.

Their moments of rest are short-lived, however. For these dorymen, there is always work to do. In the warmer months, they’re in town with their families when they aren’t on schooners heading out to Georges Bank, the Grand Banks, and other Canadian waters. But in winter they are the town’s inshore fishermen, living on the edge this way as a convenience of sorts, so they can launch daily to fish in frigid waters.

This is the true story of Helltown, according to local historian Stephan Cohen, who has spent three years reading government documents, 19th-century maps, and reports on Azorean immigration — research supported by a grant from the Provincetown Community Compact. He plans to write a book about his findings, Cohen told those who came to hear him at two talks at the Provincetown Library this fall.

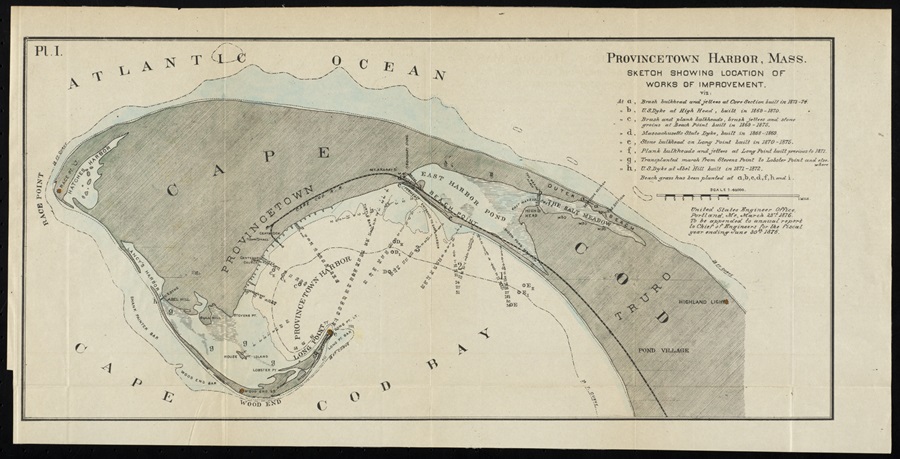

Before 1871, Cohen says, dorymen launched from Lancy’s Harbor, not far from the town’s West End. But when engineers began work on the Abel Hill dike to stop the buildup of sand in Provincetown Harbor, Lancy’s Harbor closed up. That’s what Cohen believes forced Helltown fishermen to launch from Herring Cove instead.

“It was hell spending time there in the winter, but it was also hell getting out to Helltown,” Cohen says. There was no road to the beach. The only trail to Helltown ran through a wooded area — ironically, it was called Pleasantville — west of Shank Painter Pond. Some wives would trek out to the settlement to bring their husbands warm meals. Dewing Woodward, whose Provincetown art school predated Charles Hawthorne’s, went to Helltown in 1908, Cohen says, to sketch scenes of men and women taking fish from the dories into the shacks.

The men would rise before dawn and climb, two by two, into dories powered by muscle, rowing five to six miles out to fish in frigid waters. Using hand or trawl lines, they would pull in massive hauls of cod, 700 to 1,000 pounds per boat each day. Over the course of a single 19th-century winter, Cohen figures, a million pounds of fish would be brought to shore.

The fish would be put in barrels, 200 pounds in each, and transported on horse-drawn wagons through the dunes to Provincetown. There, the catch would be put on ice and loaded onto trains bound for Boston and New York. The expenses — bait, barrels, ice, and the wagon transport by teamsters, who were mostly Irish — were borne by the fishermen. Estimates of what they earned vary, but Cohen concludes that “a doryman’s individual ‘pittance’ enabled many Provincetown families to make it through the winter.”

Cohen’s Helltown as a place of backbreaking work by immigrant fishermen doesn’t square with what most people imagine about the place. It’s commonly thought of as a nickname for Provincetown in its role as a “last call” for whalers and pirates needing a hell of a good time in port before setting sail for years at sea.

Journalist Mary Heaton Vorse, who lived on Commercial Street from 1907 until her death in 1966, apparently contributed to the lore, writing in her 1942 memoir, Time and the Town, that she was told by a fishing captain that the name “Helltown” reflected “the helling that went on there.” Helltown also appears as a crime scene in Norman Mailer’s noir Tough Guys Don’t Dance and more playfully in the name of a modern-day restaurant, Helltown Kitchen, on Commercial Street or designed into clothing and textiles featuring pirate ships at MAP, the boutique owned by Pauline Fisher.

Over the decades, Cohen thinks, some may have mistakenly merged the histories of Long Point and Helltown, although their timelines, locations, and physical scale (Long Point had salt works, a school, post office, and wharf) are markedly different.

In any case, Helltown’s demise didn’t come at the hands of swashbuckling seafarers. “What killed Helltown was the gas engine,” Cohen says. Once that was invented, “If a doryman had an engine, he could get out from Provincetown Harbor, except when things froze over.”

As for the shacks, they were moved back to town and probably used for storage, Cohen says, and there’s evidence lobstermen also used them for a while. A storage shed attached to a family home at 7 Bradford St. may have been a Helltown hut, according to local lore. There’s no question, Cohen believes, that the always-thrifty fishermen would have found ways to repurpose the lumber.

Cohen never learned the exact location of Helltown, but it was known to U.S. government surveyors, who in 1909 put in markers at the site for a track to test torpedo boat speeds. Those are now buried three feet deep.

“Like Provincetown itself,” Cohen says, “Helltown is something you can project anything you want onto.”