WELLFLEET — On his inauguration day, President Donald Trump signed an executive order meant to start fulfilling his campaign promise to kill offshore wind development “on day one.”

The executive order paused all leasing and permitting of offshore wind and directed the Secretary of the Interior to conduct reviews of current leases and identify “any legal bases” for amending or revoking them. It did not immediately cancel existing leases.

Industry experts told the Independent that it’s hard to predict whether the Trump administration will be able to end the four leases for wind energy areas in the Gulf of Maine that were auctioned last October.

“I think it’s too early to say what they can and can’t do,” said Francis Pullaro, president of the clean energy consortium RENEW Northeast. “I have a feeling the administration in Washington is probably trying to figure out how to actually follow through on these executive orders.”

State Sen. Julian Cyr agreed, telling the Independent that he is waiting to see more specific actions. “I think the details are going to matter here,” he said.

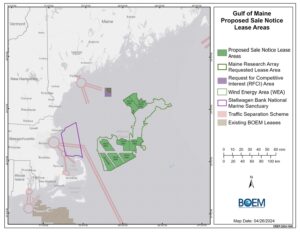

The Gulf of Maine offshore wind area has been in the works since 2019, and eight leasing areas were finalized last year. Four of them were put up for auction on Oct. 29, and two companies — one American and one a subsidiary of a Spanish energy firm — each purchased two leases.

The nearest leasing area to Cape Cod is 24.8 miles from the Outer Cape and was leased to the American company Invenergy NE Offshore Wind LLC. In an email, Invernergy communications officer Sophie Lee did not respond to questions from the Independent except to write that “Invenergy is evaluating the newly announced executive actions in collaboration with its industry partners.”

Avangrid Renewables LLC, which is a subsidiary of Iberdrola, did not respond to questions from the Independent.

The first Trump administration was not so opposed to wind energy. In 2018, the Interior Dept. approved the sale of a group of offshore wind leases south of Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard that today include the Vineyard Wind and SouthCoast Wind projects. In the press release announcing that sale — titled “Bidding Bonanza!” — then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke said, “We’ve given the wind industry the confidence to think and bid big.”

Now the agenda appears to be revoking leases, but a revocation “would put them on very thorny legal ground,” said Nick Krakoff, senior attorney at Conservation Law Foundation New Hampshire.

“That would certainly invite legal challenge, and they would have to pay compensation,” Krakoff said.

Pullaro agreed. “That would be a ‘taking’ of property,” he said, which according to the Fifth Amendment would require the government to provide “just compensation.”

“For the administration to try to do that is not without consequences for the taxpayer,” Pullaro added.

Neither Pullaro nor Krakoff were sure whether the government could simply repay the $21.9 million that the companies paid for the Gulf of Maine leases or whether it would owe more due to their additional costs.

A revocation is not the only option, though. Pullaro said the administration could instead add “speed bumps” to the development process. The inauguration day executive order directs various agency heads not to issue “new or renewed approvals, rights of way, permits, leases, or loans for onshore or offshore wind projects.”

Delays can add costs for developers that make the resulting energy more expensive for ratepayers, Pullaro said.

Because of the timing of the lease auction, however, there might not be any new approvals needed during the four years of Trump’s second administration. Krakoff noted that wind companies have five years from the date of purchase to complete surveying and put forward a construction and operations plan.

This means the two wind companies will have until October 29, 2029 — 10 months after the end of Trump’s second term — until they need to submit their plan for government approval.

“If in four years the winds shift and the next administration is keen on offshore wind again, it could fit nicely into that timeframe,” Krakoff said, “assuming they’ll be able to go out and do the surveying.”

Neither Krakoff nor Pullaro could identify a legal mechanism by which Trump could prevent wind energy companies from surveying their lease areas without revoking the leases altogether.

Even if the federal government could prevent surveying or slow development in some other way, Pullaro said, the “long time horizon” for offshore wind developments could make delays relatively less costly.

Tax Credits

There is another “speed bump” the Trump administration could seek, Pullaro said, although it would likely need the consent of Congress to use it. Financing in the wind industry relies on renewable energy tax credits, and though they might not be revocable through executive order, the Republican-controlled Congress could cancel them or let them expire.

The tax credits have briefly expired before, Pullaro said, but have always been re-established. Even temporary disruptions typically have a “chilling effect” on wind energy investment, he said, and if they were eliminated for a longer term, it is unclear “whether these projects are even financially viable.”

Investors in wind energy projects often seek tax credits and other benefits to apply to their other assets, Pullaro said. According to the American Council on Renewable Energy, tax equity investors typically provide between one-third and two-thirds of the total capital of a clean energy project.

In previous instances when green energy tax credits have lapsed, state governments in New England have helped sustain projects by pushing for more investment, Pullaro said. “The states have been consistent with their clean energy procurement policies, and that really sends a signal to investors,” he said.

Cyr said that a rollback of federal tax credits would hurt wind energy development both offshore and onshore — including in red states such as Iowa, which generates more than half its electricity from wind. Senators and representatives from those states might be reluctant to cancel the renewable energy credits, he said.

Cyr also said that the long timeline for offshore wind developments could work in favor of the Gulf of Maine projects.

“These projects are about 15 years out or more,” Cyr said. When it comes to wind power, four years doesn’t necessarily mean forever.