Imagine these woods as they were before Europeans arrived. Trees were not easily felled. Instead, fire was used to clear land, allowing roots to survive and new growth to easily emerge from the crispy humus. The Cape was tidal in the coastal areas, and salt marshes merged with fresh water in the interior. Large swathes were wet woodlands with open water, marsh grasses, and dense shrubs. Higher lands had old-growth oak, chestnut, hickory, and beech trees and with them thousands of nuts that were eaten by insects, fauna, and humans.

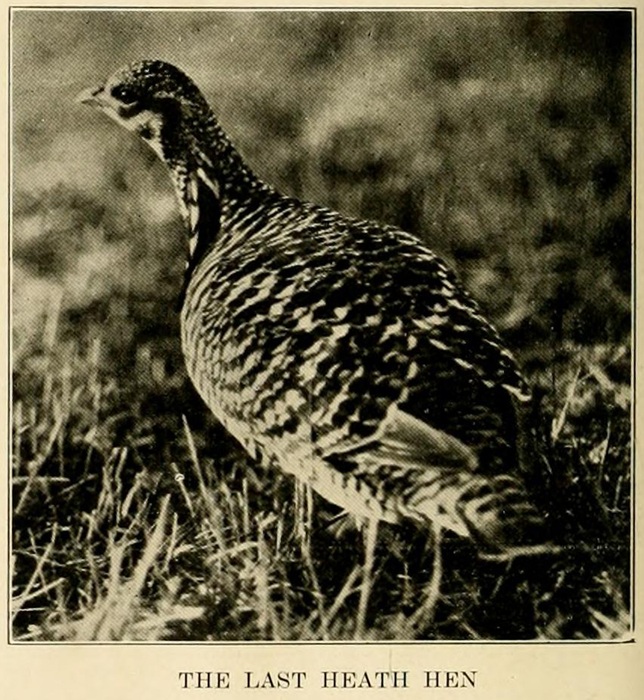

In these coastal places between forest and marsh was a grouse called the heath hen (Tympanuchus cupido cupido). It was last seen in the wild on Martha’s Vineyard in a few flocks around 1900. The last one in a sanctuary for the species there died in 1932: “Somewhere on the great plain of Martha’s Vineyard death and the heath hen have met. One day, just as usual, there was a bird called the heath hen, and the next day there was none,” wrote the Vineyard Gazette in its April 21, 1933 issue.

I was at the New York Museum of Natural History late last year and came across a dusty diorama of taxidermized specimens in a forgotten corner.

It is challenging to be a North American bird enthusiast. Knowing that our once most common tree, the chestnut (Castanea dentata), is nearly extinct and our once most common pigeon, the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), is gone brings deep pangs of grief. Our native parakeet, the Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), is gone as well. These birds flustered European farmers in the Carolinas as they descended on the easy target of plentiful grains; they were shot for it. Their bright plumage was wanted by hatmakers, too.

The heath hen suffered the same fate after being overhunted by sportsmen. The filling in of marshland and clearing of forests surely contributed to the birds’ extinction.

It’s difficult to come to terms with these losses and feel we can understand our woods. They are forever changed, the dawn chorus distorted.

The genus Tympanuchus now has three species in it, all found on the Great Plains of North America, and their names may be familiar: the sharp-tailed grouse and the greater and lesser prairie chickens. Our heath hen was a subspecies of the greater prairie chicken. So, we can look at the morphology and habits of the extant prairie chickens to try and understand how this grouse may have interacted with our New England coastal marshlands and forests.

As the common name suggests, it must have been seen more on the heath than in the woods. We may also assume it had leks — mating grounds where females observed as the males danced and put on displays to win access to multiple partners. Where would these leks have been, I wonder: the parking area of Wellfleet’s Dunkin? Perhaps farther out, where Crowne Pointe now sits in Provincetown?

A few ornithologists were able to document some of the habits of the heath hen. Bowdoin College ornithologist Alfred O. Gross was the last to study them in Maine, observing from a blind and describing in detail the thrill of the male call, like a “muffled blast of a tugboat” in the predawn chorus. He observed them leaping up to four feet in the air while letting out a “wwrrrrb” sound “followed by a curious indescribable laughterlike sound.”

Gross observed them eating scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia) year-round and wrote that partridge berry (Mitchella repens) was referred to by early settlers as the heath hen plum. These references only increase my curiosity about how these birds fit within this ecosystem.

Its eggs are described by William E.D. Scott in his 1898 Bird Studies as being 1.75 inches long, olive green, and “laid in nests situated on the ground in oak woods at the base of a stump.” Scott makes the prescient argument that “persecution by gunners cannot alone account [for its rapid extinction] … There can be no doubt that the settlement of the country has much farther reaching results and influences on the original fauna than is generally ascribed to it.”

Populations are always moving, and change is the one constant in life. What is hard to come to terms with is the finality of losing this bird.

At some point, all of us will experience the loss of a parent who insulated us from the harsh experience of life’s vicissitudes. When parents die, we understand that it is a natural occurrence, but what is harder to comprehend is that they will never be coming back; their voices are gone; their touch on the space is now that of a ghost. We will never again see them stride across the landscape but will be forced to carry them forward in our memories and imaginations.

And so it is with our lost heath hen.