Edward Rowe Snow, the master chronicler of New England sea stories, wrote a letter to the Provincetown Advocate in February 1964, seeking information about descendants of Capt. David H. Atkins, whom Snow called an “outstanding Life Saver of a former generation.”

Snow mentioned, enigmatically, “a shadow” over Atkins’s name, and wrote that his purpose was “to right a wrong of eighty years.” What were Advocate readers to make of Snow’s letter and what was the “wrong” to which he alluded?

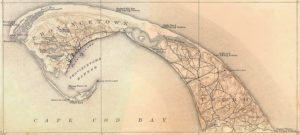

David Henry Atkins, the son of Henry and Esther, was born in Provincetown in 1834. When the Peaked Hill Life Saving Station — one of the original nine Cape Cod stations — was completed and equipped in January 1873, Atkins, who had spent a decade in service with the Humane Society (the forerunner to the Lifesaving Service), was appointed its first keeper.

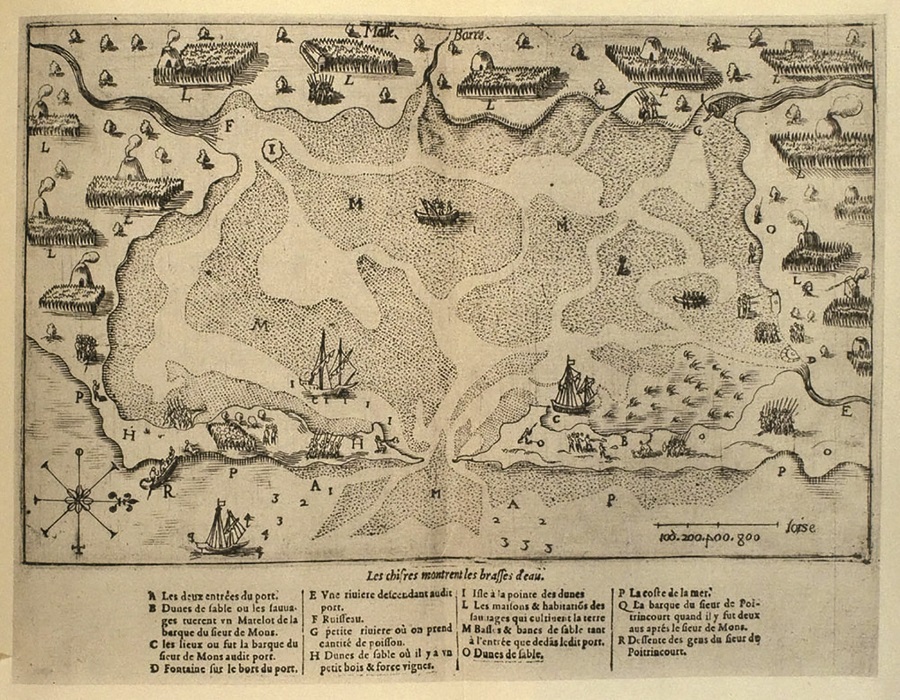

On the morning of Nov. 30, 1880, a northerly gale swept across Massachusetts Bay, tightening its grip on the C.E. Trumbull, a sloop from Cape Ann. Built in 1870 and of a sturdy design to carry granite paving stones, the C.E. Trumbull, with its crew of six including the captain, was homeward bound in ballast from New Bedford when it stranded at Peaked Hill.

The six-man crew of the Peaked Hill Station sprang into action, launching a surfboat, rescuing four from the sloop, and landing them safely ashore. Returning to the sloop to rescue the captain and pilot, who, it was reported, had initially refused to leave without their personal effects, the surfboat was capsized by the sloop’s swinging boom, flinging its crew into the churning seas. Three of the lifesaving crew managed to swim ashore in the numbing cold, but Capt. Atkins, Stephen Frank Mayo, and Elisha N. Taylor, desperately clinging to the surfboat, were washed off. All three bodies were eventually recovered.

As the tide turned and the sandbar loosened its grip on the C.E. Trumbull, the captain and pilot, still on board, were able to float her off. They were outfitted with new sails at Chatham and returned to Rockport, from where the sloop continued to sail for several years. Provincetown was left with its losses.

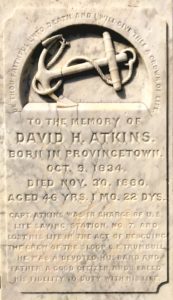

In Provincetown’s Gifford Cemetery, a handsome monument with an anchor motif — a symbol of safety and hope — stands To the Memory of David H. Atkins. He was, reads the inscription, “a devoted husband and father, a good citizen and sealed his fidelity to duty with his life,” a tribute that offers no hint of earlier events that haunted Atkins, casting the shadow to which Edward Rowe Snow had alluded.

Five years earlier, on the morning of March 4, 1875, the bark Giovanni, bound for Boston from Palermo, Italy with a crew of 16 and a cargo of sumac, nuts, and brimstone (sulfur), encountered a raging nor’easter. In blinding snow, with sails shredded, mountainous seas sweeping the deck, and soundings confirming the lessening water depths, all eyes searched for guidance from the Highland Light. By early afternoon the crippled vessel had stranded at Peaked Hill.

The crew from the Peaked Hill Station, under the direction of Keeper Atkins, as well as the crew from Highland Station led by Keeper Edwin P. Worthen, responded promptly. Given the ferocious conditions, no attempt was made to launch the surfboats. Three attempts to shoot a line from the mortar apparatus to the foundering vessel were unsuccessful. Only one Giovanni crew member, the steward, survived the wreck. He had fastened himself to a plank and let the surf convulse him ashore. Fifteen others perished, a devastating loss of life for the nascent lifesaving service.

Anonymous criticism weighed on Capt. Atkins afterwards, with newspapers reporting his cowardice, tactical shortcomings, and the worthlessness of his equipment.

Salacious stories circulated that a mob of salvagers had consumed cases of wine washing ashore (it could not be determined if the wine was part of the cargo or the ship’s stores), and that a frenzied, drunken orgy ensued, resulting in the bodies of drowned crew members being robbed and four deaths — murder being insinuated — among the wreckers.

A full investigation of the tragedy found that “every exertion within their power to rescue the crew” had been made by the lifesaving crews and that the vessel had been “beyond the reach of any life-saving apparatus.”

The shadow lengthened for Capt. Atkins in April 1879, when the three-masted schooner Sarah J. Fort wrecked at Peaked Hill. For 12 exhausting hours, Atkins’s crew attempted the rescue with both surfboat and the line-throwing Parrott gun, only to watch as the rescue of four sailors (two had drowned) was accomplished by a volunteer crew, fresh from town, led by Capt. Isaac F. Mayo.

Mayo was later awarded a gold medal for his service. Meanwhile, Atkins again felt the sting of criticism that he had failed to employ the newer model Lyle gun that could have established line communication with the wreck and completed the rescue hours earlier.

In the aftermath of the C.E. Trumbull tragedy, a Lifesaving Service report suggested that the earlier criticism aimed at Atkins had made him determined to “spare no hazard, however desperate, in the future discharge of duty.” It was in this spirit, concluded the report, “and with this resolution, that he found his duty, and met his death.”

A trusted and dedicated veteran of the Service, Atkins was called upon time and time again to confront dangers before which most men would wither. None but his fellow lifesaving crew members could know those dangers, and they stood by him, never questioning his courage.

In his 1964 book The Fury of the Seas, Edward Rowe Snow added his voice to theirs, and lifted the cloud over Capt. David H. Atkins — one that “never should have been allowed to gather around either his name or his actions.”