EASTHAM — George FitzGibbons became interested in bat boxes out of frustration. Not with bats, but with bugs.

“My wife hates mosquitos,” he says. They would drive her nuts during outdoor meals here, he adds, gesturing to the large flowering garden on his mother-in-law’s property in Eastham.

In 2019, he started reading about bats and how they might help cut down on mosquitos. He purchased a bat box online, but “it was just particle board, and really flimsy,” FitzGibbons said. Soon he was researching ways to construct a sturdier home for bats. He found some boxy styles, and, combining those with features he liked about his original purchase, gradually created a sturdy, handmade cedar bat box.

The next year, the pandemic turned FitzGibbon’s construction experiment into what he calls “an aggressive hobby.” Decamping from Boston, he and his wife, Tessa Herbert Rudd, who grew up in Provincetown, and their daughter, Blair (who now has a brother, Jack), moved into his mother-in-law’s home, where FitzGibbons converted part of an old barn into a woodshop where he could produce more bat boxes.

“It was a merger of a lot of things I’m interested in,” FitzGibbons says, naming ecology and forestry, which he had studied at the University of New Hampshire. And, he adds, “It was an excuse to buy a lot of tools.”

At first, he gave the boxes to friends and family. But as a software engineer working predominantly in e-commerce, FitzGibbons had the chops to use digital tools, in addition to wood and saws, to turn his hobby into a business. He built a website, posted the boxes on Etsy, and started selling 5 or 10 a week to people from all over the country. Today his business, BatboxCo, is one of the top results on Etsy when one searches for bat boxes.

Now living in Marshfield, FitzGibbons comes to the Cape on weekends. On Sundays, he assembles about 10 bat boxes over the course of a couple of hours in the barn, which is crammed with lumber, a grill, African masks, and sundry tools. Mark Evans, his business partner and childhood friend, fabricates a similar number each week in Austin, Texas.

The boxes come in two sizes, with the small ones holding up to 30 bats and the large ones up to 100. The backplate, cut through with half-inch grooves, hangs below the front plate, providing a landing pad for the bats. The design allows the bats to “crawl up and hang,” Fitzgibbons says. “It mimics a cave.”

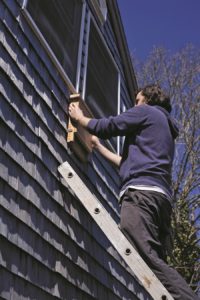

The boxes ship unstained, because the further north they’re to be used, the darker the stain should be. That helps keep the interior warmer. “Heat is the number-one priority for them,” FitzGibbons explains. He recommends hanging the boxes on the side of a house, about 15 feet off the ground, where they will be safe from predators. “The ideal place has lots of sun during the day and is dark at night,” he adds.

FitzGibbons keeps the price of his boxes reasonable. The bottom line isn’t his biggest concern, he says. And neither are mosquitos. “I want to sell as many bat boxes as possible from the perspective that bats need homes,” he says.

FitzGibbons has learned a lot about bats since he first started building boxes. For one thing, they eat all kinds of bugs, and they like beetles even better than they do mosquitos. So, he’s cautious about making grand claims about the bat boxes being used for mosquito control. But in his own family’s yard, he says, he’d like to think the boxes have helped.

He also learned that bat populations have suffered a decline over the last decade because of white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease. “I think there is some good in just knowing that you’re giving a bat a home,” he says. “Bats are strained right now.”

Jennifer Longsdorf, the Natural Heritage Program coordinator at Mass Wildlife, explains that the disease was first discovered in Massachusetts during the winter of 2008-2009. Killing more than a million bats each year, the white-nose syndrome is commonly spread in caves where bats hibernate.

Because it offers a diversity of habitats, Cape Cod is home to many species of bats, says Longsdorf. But their numbers are decreasing locally. Mark Faherty, science coordinator at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, describes how the little brown bat “used to be common, like a chickadee,” but is now considered endangered in Massachusetts.

Although white-nose syndrome has been detected on Cape Cod bats, Faherty is cautiously optimistic that it isn’t widely transmitted here because the bats that winter here don’t live in large, crowded caves. For the bats that migrate, however, the situation is more perilous.

In addition to the threat of disease, FitzGibbons notes that bats’ habitats are increasingly threatened in some areas. He explains that they love roosting in the bark of dead trees or snags — standing dead trees. “The next best place is inside a house or barn,” he says, “but they get kicked out quickly.”

Faherty points out that “Cape houses function pretty well as bat houses,” providing shelter under rake boards, beneath shingles, and inside attics. For those queasy about bats in their houses, Longsdorf says, “Installing a bat house can reduce human-bat contact.”

Longsdorf also argues that “bats absolutely need habitat,” adding that is why “Mass Wildlife initiated the bat house project to get more bat houses out on the landscape.” And besides their mosquito-eating, Longsdorf says, “their poop is great for gardens!”

Faherty is not so sure that having a bat box means your mosquito problem will disappear. But, he says, “More bats are better than fewer bats.” He welcomes anyone to challenge his bat box skepticism by informing him of successes with their contraptions.

Whether or not bats can devour enough mosquitos to alleviate the itching Outer Cape residents have endured in recent years, FitzGibbons has become a defender of these maligned and threatened mammals. “You can invite them onto your property, and they’ll help your garden,” he says. “They’re good neighbors.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on April 28, mistakenly identified George FitzGibbons’s and Tessa Rudd’s daughter, Blair, as a son.