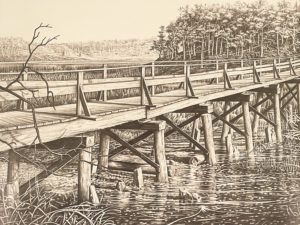

On an early spring day, Neal Nichols Jr. stands on Hamblen Island in Wellfleet, overlooking Duck Creek and Wellfleet Harbor. “I have a photographic memory,” he says, tracing the view with his hand. “When I look at a landscape, my mind absorbs every detail: the trees in the foreground, the old train bridge. Later, when I sit down to replicate what I saw, it all comes back to me.”

Born in Bridgewater, Nichols grew up first in Wellfleet, later in Eastham, where he lives today. His mother, Cynthia Souther, married a local fisherman but was left to bring up seven children on her own. Nichols had barely outgrown his crib when she observed that he saw the world differently than others.

“My mom likes to say that I was born with 10 fingers and a pencil,” Nichols says, chuckling. “I started drawing in the high chair, and not just scribbles. I would try to draw the refrigerator, and I’d have to see all the sides of it.”

When he began school at Wellfleet Elementary, “People thought something might be wrong with me, because I was drawing all the time,” he says. But his third-grade teacher recognized Nichols for what he was. “Mrs. McAuliffe asked, ‘What’s wrong with a kid who loves to draw? He’s an artist!’ ”

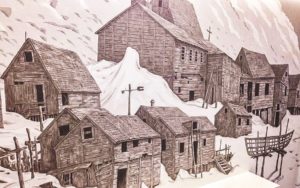

By middle school, Nichols had taught himself techniques of perspective in drawing. His favorite subjects were rundown old houses and barns, and they’re still the focus of his art today. Some may consider such structures eyesores, Nichols says, but he sees in them “the deep darks created by missing boards, the contours in twisted and aged wood, the color vibrancies of peeling paint, and the variations of texture, perspective, and detail.”

One of his middle school teachers, Marie Jones, was the first to buy one of Nichols’s drawings. “I did a little Cape Cod scene, and she gave me $5 for it,” he says. “We weren’t rich. My mother was raising us on her own by then, so I was able to throw a little extra on the table.”

At 14, Nichols became the youngest artist to exhibit at the Marine Arts Gallery in Salem. The gallery’s curator, Jim Ferguson, had heard of a prodigy and showed up at the family’s house. He bought every one of Nichols’s drawings on the spot. “Mom came home to bare walls,” Nichols remembers, smiling.

By the time he was in ninth grade, he was taking on commercial work. “I’d ride my bicycle all over the place and illustrate,” he says. “A realtor paid $100 for a drawing back in those days. I gave the money to my mother to help support us.”

Jim Owens, then an art teacher at Nauset Regional High School, encouraged Nichols to apply to Mass. College of Art, where he was accepted to study illustration. Partway into his studies, however, the state changed its student finance policies, and Nichols could no longer afford to go.

“I was one of those kids who fell between the cracks,” he says. “I ended up going into truck driving and construction to pay the rent, but I was illustrating all along — some ads for magazines and newspapers, and a few editorial drawings.”

Nichols married a fellow art student from Japan and moved to Tokyo with her. The marriage didn’t last, but, living abroad, Nichols discovered his passion for world travel. By his count, he has taken 2,037 flights around the globe.

Wherever Nichols traveled, he drew what he saw, and retained the memory of contours and shapes. In 1992, he was doodling a map of Europe on a napkin for a friend when a teacher noticed the striking accuracy of what he drew and invited him to visit his class.

“I don’t like the structure of school,” Nichols says, “but I did it, and the kids loved the show. I didn’t know a career in ‘educational entertainment’ existed.”

Nichols now makes a living by presenting his “Geography Gameshow” in schools all over the U.S., as well as Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, where his son, Seiya, runs an orphanage.

When Nichols gets hired by a school, he makes it a point to get to know the community and participate in local projects, such as a mural for the town of Shaktoolik, Alaska, of an abandoned settlement on the Diomede Islands. “I’m passionate about working in these most remote Native villages,” he says.

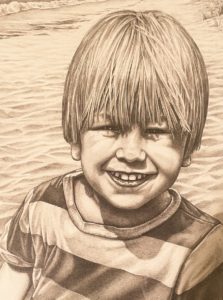

Despite his travels, Wellfleet remains his favorite place, Nichols says. Every summer he teaches children’s art classes through the Wellfleet Recreation Dept. “There was a four-year-old boy who could do three-dimensional drawings after my class,” he says proudly.

Though Covid shut down his travels, he’s managed to keep himself busy. He’s currently recording a series of drawing classes on video with Ivan Rambhadjan, director of operations at the Cape Media Center.

Nichols doesn’t regret taking an untraditional route to becoming a working artist. “I’ve never done anything the usual way,” he says. “I love to teach, but I’m not a teacher. I love to fly planes, but I’m not a pilot. When you turn something into work, you kill it. I get to dictate the rules, and I wanted my life to be like that.

“Making art is like putting your soul on paper,” Nichols adds. “When you find your style, your creativity becomes something you don’t even think about, like signing your name. If you can make that happen, you’re leaving a piece of yourself with others.”