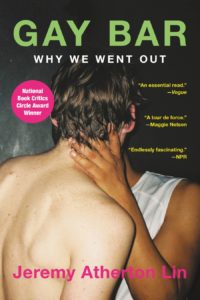

Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar: Why We Went Out is a memoir of a booze- and sex-soaked search for identity. Despite the subtitle, it’s really about why he went out: to find something he could identify with that would last beyond last call. Originally published to widespread acclaim in early 2021, the book was issued in paperback this summer.

The “we” part depends a lot on the reader’s own experiences. Mine was roughly the same as Atherton Lin’s, which began in the late 1980s. Though the book jumps through time and space, his stories are mainly set in the three cities where Atherton Lin spent most of his young adult life: San Francisco, Los Angeles, and London. This was my turf too, making for a discomfiting read as it dredged up a lot of memories I thought were safely suppressed. Atherton Lin has an exceptional ability to break through the pretenses we used to construct our youthful egos. Both intellectual and dirty, he quotes philosophers and describes lurid sex acts in a chummy cadence. It’s a fast read, but it doesn’t all go down easy.

As he moves between cities and lovers, Atherton Lin describes the habitués, fashions, and attitudes of the bars he spent time in, distilled through his own experiences of being desirous and desired, rejected or belonging. In most places, he does not find the identity he craves. “I saw these men as being in their domain, depraved and sketchy,” he writes, “whereas I was just passing through.”

The majority of the bars Atherton Lin visits in his early going-out years were created by and for white gay men. (Lin is biracial but offers only passing references to that fact: “He said he’d detected there was something oriental about me. Oriental is for rugs, I corrected.” The takeaway is that he looks white and uses it to his advantage.) Fashion and body type were the primary currency to gain entrée into gay subcultures in the ’80s and ’90s. Each bar had a look — leather, muscle, twink, cowboy — and each one had unbreakable rules about what you had to look like to get in and how you had to act once you did.

This was true for me. In 1987, desperate to gain entry, I was constantly trying on different looks that always felt like Halloween costumes. I eventually figured out that some eyeliner, teased hair, ear cuffs, and a clove cigarette would get me past the bouncers at San Francisco’s Club Kabuki. It wasn’t where I wanted to be, but at least I was somewhere. We went out to get in.

Outside Studio One in West Hollywood in the early ’90s, Atherton Lin lines up with the white, young, and super-buff men he describes as having teeth so white they looked perpetually ready to shoot a toothpaste commercial, and he manages to get in. But while I was white and young — and despite brushing my teeth so frequently the enamel wore off — my spindly muscles never made it past the parking lot. The image of strength these muscle boys projected was a rebuke to the fear of AIDS when the disease was still a frightening mystery.

In London, Atherton Lin adopts the popular affectation of track suits and hoodies: the normative look of working-class straight men, often the same men who would attack them outside the bars. In San Francisco, the ubiquitous mustache and Levi’s in the South of Market bars projected hyper-masculinity and a similarity that made each man nearly indistinguishable from the next. “Clones,” as they were called, held off the dreaded “otherness” and provided an acceptable gay identity without the hassle of individuality.

Though Atherton Lin acknowledges the benefits of bars evolving from bunker-like, frequently unmarked addresses in dark alleys to ones with plate glass windows fronting fashionable streets, he is critical of the influx of straight patrons — primarily the groups of straight women for whom gay culture is now a major draw. His description of an encounter with a woman who wanted to snatch his boyfriend’s hat for a selfie will resonate with many readers: “Her continued persistence was a minor, maybe harmless incident. But both of us found ourselves wanting to say: An ally is there to join, not conquer. We aren’t here to lend you props for a makeshift micro appropriation. You can party with us but give us a little respect.”

With growing acceptance, are exclusively gay bars (and, by extension, events) still even necessary? Viewed through the prism of Gay Bar, Provincetown’s cash-generating summer theme weeks, each one targeting a specific queer demographic, seem headed toward extinction. The younger generations, Atherton Lin tells us, now favor all-inclusive spaces without labels, dress codes, or rules about gender conformity. He notes a 2019 poll in The Telegraph, a London newspaper, in which young Britons state that they are half as likely to identify as gay or lesbian and eight times more likely to identify as bisexual than they were just four years earlier. And the current trend toward the even less categorical term “nonbinary” is growing exponentially. As one particularly angsty friend recently said to me, “My whole life I was tormented for being gay, and now, seemingly overnight, being gay is passé.”

Ironically, the most pertinent evidence in Gay Bar that big changes are likely in store for Provincetown comes from a study authored in 1985. A group of sociologists argued that a real community must be “a community of memory” that remembers its past, including shared suffering. When that history is forgotten, the community will devolve into a “lifestyle enclave” that puts leisure and consumption above the common good. Is that us? Only time will tell. But until it does, we, like Jeremy Atherton Lin, still have our memories — and maybe an old ear cuff.