Kevin Rita, owner of Garvey Rita Art & Antiques in Orleans, went to Bologna, Italy last fall and visited Museo Morandi, a museum dedicated to the work of Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, and Casa Morandi, his home and studio. Morandi is best known for his seemingly simple paintings of bottles on tabletops.

“I’ve always been drawn to work that has a connection to Morandi,” says Rita. When he returned to the Cape, he began gathering works from his collection and from artists he admired that he felt related to Morandi’s penchant for finding magic in the mundane.

The resulting densely hung exhibition, “Nothing Is More Abstract Than Reality,” is less spartan than Casa Morandi but evokes a similar sense of history. The show features 22 artists working in a range of styles united by the idea of looking closely as a means of invention.

Casa Morandi preserves the space as it was when the artist worked there. “There are two of his hats stacked on each other and his rather pallet-like bed,” says Rita. The shelves are lined with the objects he famously painted: vases, tins, and bottles. The modest dwelling, which Morandi shared with his three sisters, represents the confines that he worked in physically and metaphorically. He lived there for 31 years before his death in 1964. He left Italy only three times, and aside from summers spent in the nearby mountain town of Grizzana, his creative practice happened at home.

Morandi’s work illustrates the expansion that is possible within limitations. Objects turn into vessels for explorations of value and color. They also contain philosophical concerns. “They start to become about the way we look, the way objects occupy space, and the way we apprehend space,” says Rita. “They can forever give. You never quite possess them.” In Morandi’s art, paintings of bottles are paintings about the expansiveness of existence.

Artist and critic Sidney Tillim wrote that Morandi was “both ahead of his time and behind it.” He drew a link between Morandi’s still lifes of white objects and the sculptural forms of Italy’s classic past. Other critics have noted connections between Morandi and the minimalists that followed him. The David Zwirner gallery in New York currently has an exhibition covering six decades of Morandi’s career.

A few of the works in Rita’s exhibition make specific reference to Morandi, like Nostalgia, a monoprint by Truro artist Megan Hinton. This piece, part of a series where Hinton lifts images from the work of other painters, isolates one of Morandi’s jugs. It fills Hinton’s composition, presented like a relic or symbol. Slashes of sooty ink cast the object as a vehicle for material play and emotional projection.

Janice LaMotta, who ran a gallery with Rita in Connecticut, also directly references Morandi in Paesaggio (Homage to Morandi). The landscape painting, created with quick, brushy strokes, recalls Morandi’s landscapes with its pale earth tones and the overall flatness of the image. Philadelphia artist Stuart Shils’s green Italian landscape hangs next to LaMotta’s. Like Morandi, Shils uses subtle shifts of color and value to economically articulate deep space.

Aside from LaMotta and Shils, the other works in the exhibition generally take objects or still lifes as their subjects. Some pieces relate to Morandi’s use of color, others to his flirtation with abstraction or his spiritual and philosophical leanings.

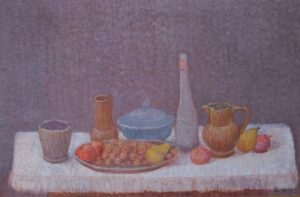

There’s a piece by Leon Hartl, a French émigré who painted during the 1950s and ’60s. The work, which depicts a tabletop laden with fruit and various dishes, remembers Morandi in its subject as well as its muted, dusty colors applied in delicate, stippled brushstrokes. The vases of different heights create a vertical rhythm in contrast to the steady horizontal presence of the tabletop.

Ruth Miller also takes a collection of objects as her starting point, but her painting is as much about the green kettle and melon as it is about the space between them. “Light never convinces unless it has space to fill: Morandi’s subjects exist in space,” wrote art critic John Berger. Miller, who had a show in 2023 at the New York Studio School honoring her “meditative and honest portrayal of the world and objects around her,” articulates a finely tuned space in her painting. The pale light on one end of the melon pulls the object forward and away from a dark green bottle and yellow object in the background. One could easily imagine the eggs in the foreground rolling back into that convincing space.

Hartl’s and Miller’s paintings are situated within a tradition of still life painting, but, like Morandi’s, the approaches differ from most historical examples. “Morandi is not a still-life painter in the tradition of the great Dutch and Spanish still-life painters, where it’s usually a kind of memento mori,” says Rita. “For Morandi, it’s much more of an investigation of space.”

There is, however, one memento mori painting in the show by Gandy Brodie, who painted extensively in Provincetown and died in 1975. A skull on a tabletop among four black radishes suggests mortality. It’s a heavy painting with brooding colors, rough shapes, and thick, dirty layers of paint. Like many of Morandi’s paintings, it slides into the territory of abstraction. The radishes are more discernible as round shapes than vegetables.

Abstraction, as well as an insistence on the “thingness” of objects, connects Morandi to the modern artists — and poets — of his day. Rita mentions Hart Crane’s poem “Sunday Morning Apples,” about a still life by the poet’s friend William Sommer. “He’s describing what he’s seeing and what he thinks the artist is seeing, but at the end of the poem, there’s this declarative: ‘The apples, Bill, the apples.’ There’s a sudden assertion about the thingness of the thing,” says Rita. Many of the paintings of objects in this show suggest abstract concepts but are still insistent on the material qualities of the objects themselves.

Take a watercolor of a red flower by Julia Felsenthal, an artist who lives in Orleans and Brooklyn. The object could evoke thoughts of mortality or romance, but Felsenthal’s handling of the subject is more matter of fact. She insists on a microscopic, objective investigation of every petal. It recalls the poetry of William Carlos Williams, or Gertrude Stein’s famous line, “A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.”

Susan Jane Walp’s painting perhaps encapsulates the spirit of Morandi most fully. There’s a quotidian, practical quality to her objects: two bricks, a ceramic vase, and a black fruit bowl with elongated handles. Walp, a Vermont artist, has made a career of painting objects like these (grapefruit are another favorite object). There’s a humility inherent in her subjects but also in the full attention she gives to them. Observation becomes an act of devotion and an opportunity for transcendence.

Rita’s exhibition makes a case for paintings of subjects easily overlooked. Morandi’s pictures have “the inconsequence of margin notes, but they embody true observation,” wrote Berger. This duality exists in his work and the pieces in this show. They’re both ordinary and profound. It’s a paradigm, says Rita, “that art and painting is a serious business.”

Observation as an Act of Devotion

The event: ‘Nothing Is More Abstract Than Reality,’ a group exhibition

The time: Through April 20

The place: Garvey Rita Art & Antiques, 213 Main St., Orleans

The cost: Free