July 5, 2025

Orleans

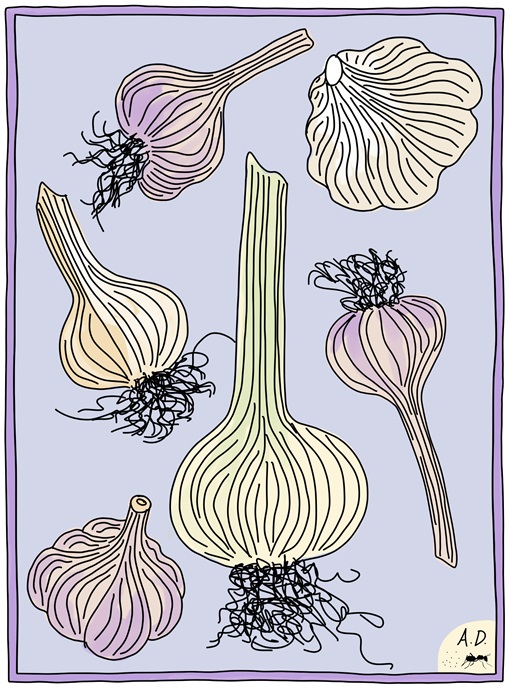

Garlic has come early to the market, a result of dry and hot weather. Many farmers have garlic on offer, but Benjamin Chung of Caroline’s Corner in Orleans has over 30 varieties, all with different flavors and appearances. A few of note: Elephant garlic, which has huge bulbs, a mild flavor, and is closely related to leeks. Nauset Red is a local garlic variety with purple coloring that Chung has been cultivating for more than a dozen years. It’s mild straight out of the ground but becomes more pungent as it ages. Xian (pronounced “she-ann”) is a type of Chinese garlic that falls somewhere between a hard- and soft-neck variety. It tastes sweet when first harvested. —Antonia DaSilva