ORLEANS — There’s a cleaver clamped to the ceiling of the Galley West Art Gallery on Monument Road. It was left there by the cook of the Orissa, a ship that was wrecked in a snowstorm off Nauset Beach in 1857. The galley of the ship, where meals were prepared and eaten, now has another life displaying works of art.

“You can tell by the shape of the roof and the feeling of the space that you’re on a ship,” says Debbie Winnick, a ceramicist who shows at Galley West. The space has an arched ceiling, and its walls slant inward. “This makes it quite challenging to hang a show,” notes Winnick.

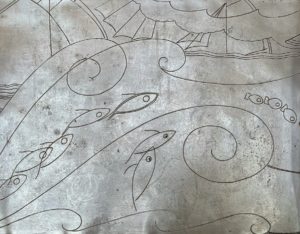

The original wood from the ship is supported by newly plastered walls and a wooden floor painted glossy white. On one wall is a recently restored mural painted by Vernon Smith in 1933 depicting the adventures of whalers. Dolphins, squid, and fish appear within circular wavelike forms. Towards the top, a schooner crests a wave in pursuit of a whale; on the left are tropical plants and islanders in traditional costumes.

The galley found its way to this Orleans property, now the campus of the Church of the Holy Spirit, after it washed up on Nauset Beach in 1894. A family living in what is now the front portion of the art gallery salvaged it for added living space. The current structure combines two historic buildings: the galley and a half-Cape, which has its own story: it is believed that this two-story front portion was a small outbuilding of the Higgins Tavern and Inn in Orleans, where Henry David Thoreau stopped for a night, as he wrote in his book Cape Cod.

This hybrid building and an accompanying four acres were purchased in 1928 by Florence Kimball, who with her husband, Richard, were important local figures.

“Monument Road was a little microcosm of left-leaning people,” says Dan Joy, the grandson of Vernon Smith. Along with the Kimballs, Smith was central to fostering a creative and politically minded community in Depression-era Orleans.

When Joy visits the galley, he imagines his grandfather socializing with the Kimballs, who lived in the space, and their friends. “I always feel the sense of these fellows sitting around the pot-bellied stove and talking politics,” he says.

The group attended an Episcopal church in Barnstable but desired their own congregation and persuaded Richard Kimball to serve as minister. The galley was the site of some of their first services, but the congregation quickly outgrew the space and began constructing a chapel on the property with timber salvaged from the Chequessett Inn in Wellfleet, which was destroyed by a hurricane in 1934.

Joy likens the humble beauty of the church and its scale to Cape Cod houses of that era, which were “tucked down into the environment” and typified by small low-ceilinged rooms. “The church started small and stayed small,” says Joy. It remains modest, sitting in a hollow at the juncture of Monument Road and Route 28.

The floor plan is laid out in the shape of a cross. The wooden pews, paneled walls, and ceiling beams create a warm atmosphere. Vernon Smith’s artwork — among the strongest site-specific public art in the area — enriches the space, combining Christian iconography with images of the natural world. “Vernon was always the one able to donate his talents to anything that required an artistic vision,” says Joy.

Above a door hangs a multi-panel painting by Smith. Biblical symbols — including trees, doves, and water — are combined with scientific motifs like a cell, a moon, and a sand dollar. It’s an ecstatic, mystical vision rooted in religion and the Earth.

Smith also decorated wooden objects throughout the church, including a pair of doors adorned with trees, end carvings on the pews, and a bishop’s chair. His standalone wood carvings alternate between rhythmic abstractions and more overtly religious iconography, such as a Madonna and child sitting on a bale of hay. A carving of flames reads both abstractly, as quivering vertical forms, and devotionally, as an allusion to the Holy Spirit.

Aluminum was another of Smith’s favorite materials. He taught his metalwork techniques to Florence Kimball, a weaver who raised goats. One of the many wall sconces in the church features a baptismal scene with local references: a whale’s tail and sailboat rise in the distance. They shared the craft with others, establishing the Kimball Guild, which is still active; its members create hammered aluminum jewelry and other functional art.

With the galley empty in 1940, the guild used the space to set up a gift shop to sell their wares. “They had a vision of how they could bring in a little money to help them live during the Depression,” says Joy. The Galley West Craft Shop continued until 2019.

In the summer of 2019, the church decided that a new direction was needed for the galley. “It had no insulation and was unenhanced since the buildings had moved there,” says Sue Sasso, who, along with fellow church member and Orleans resident Sharyn Laughton, spearheaded an effort to restore the space and turn it into an art gallery. With funding from a historic restoration grant, the space was restored by contractor J.C. Donald and Russ Karber. The Art Rescue and Restoration Company in Dennis restored the mural.

Open since October 2021, the gallery hosts seasonal shows, with art selected by a rotating juror. Submissions are open to artists from the Lower and Outer Cape. “We’re an all-volunteer gallery,” says Winnick.

Joy sees it as continuing a long-held tradition central to the ethos of the church’s founders. “What they have,” he says, “is a very contemporary iteration of the impulse and the collective effort of the artists back then.”