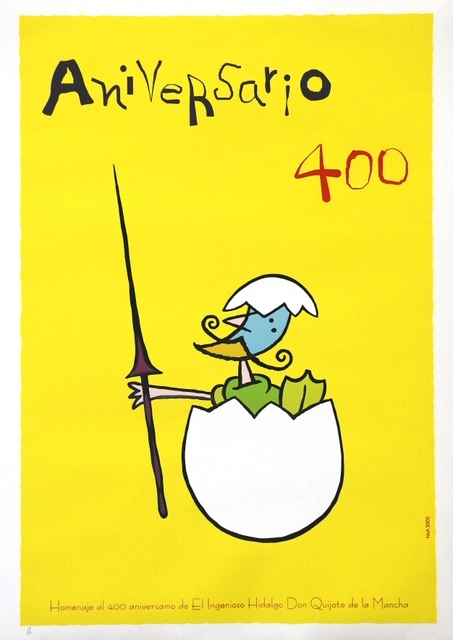

Luis Rodríguez Noa, a young Cuban painter and graphic artist, won first prize in his country’s National Contest of Posters in 2005 for a witty entry commemorating the 400th anniversary of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The poster, later reproduced on a Cuban postage stamp, advanced an artistic career that Rodríguez Noa could not have imagined when, at 14, he traveled 600 miles from his home in Guantánamo province to attend the National Art School and later the High Institute of Industrial Design in Havana.

Around the same time, Michelle Wojcik was embarking on her own seemingly quixotic venture. An anthropologist specializing in human rights and international development, Wojcik resigned from the World Policy Institute’s Cuba Project and opened Galería Cubana in Provincetown, a one-woman battle against the then 45-year-old U.S. embargo. Wojcik’s gallery and the art tour to Cuba that she leads every January aim to educate Americans who have little exposure to Cuban culture.

The 14 people (including this writer) who joined Wojcik last month visited Cuban artists in their homes and studios and discussed the tangled histories of our countries with Cuban intellectuals and entrepreneurs. We returned with a deepened appreciation of our shared reality.

“For decades, Cuban artists have made art under impossible circumstances,” writes Colombian journalist Salomé Gómez-Upegui. Those circumstances include Cuba’s dire economy, limited access to materials and markets, and occasional government persecution, prompting some of the country’s best-known contemporary artists, such as Coco Fusco and Tania Bruguera, to emigrate.

The art we saw was extraordinary. Havana’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes was a revelation. For many in our well-traveled group, the quality of the works there — by Wilfredo Lam, Raúl Martinez, Antonia Eirez, Mariano Rodriguez, Carlos Enríquez Gómez, Amelia Peláez, and Roberto Fabelo, among others — rivaled the modern collection of any museum in the world.

U.S. gallerists committed to promoting Cuban art face maddening challenges. Despite a 1989 federal court ruling that classified art produced in Cuba as “informational materials” exempt from the sanctions of the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act, Wojcik has had to ship imports to Canada and has faced resistance in carrying them across the border. U.S. banks have sometimes refused to process her payments. And President Trump’s gratuitous redesignation of Cuba as a state sponsor of terror 10 days before he left office created additional barriers to travel, commerce, and international investment.

Our government proscribes tourism as a purpose for travel to Cuba. Our group proceeded under the allowable rubric “support for the Cuban people” and dutifully patronized only privately owned restaurants and casas particulares, not state-controlled hotels. We were all too aware of the irony and moral complexity of our presence there. Driving into Havana from the airport, we passed 12-hour gas lines but learned that private tour buses like ours could refuel quickly at stations open only to them.

Many Cubans welcomed us with great warmth and generosity. “It is a struggling society but a superbly open and warm one where people care about each other and are honest to a fault,” said the co-leader of our tour, Sylvia Rozwadowska-Shah, whose Colibri Travel & Tours specializes in Cuba. “And the second amazing thing about Cuba is the arts. Art is really a religion that every Cuban believes in and practices, whether it’s dance, music, or the visual arts.”

Havana’s Bordón family is a case in point. In the canvases of Edel Bordón, the longtime chair of painting at the Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes, color and line, freedom and containment, the individual figure and the human mass, are held in exquisite, evocative tension. The work of his wife, the sculptor Yamilé Bordón, explores the relationship between functionality and transformational potential in the design of everyday objects. Their son Pablo Bordón, an art photographer, produces images that both document and abstract the landscapes and material realities of Cuban life.

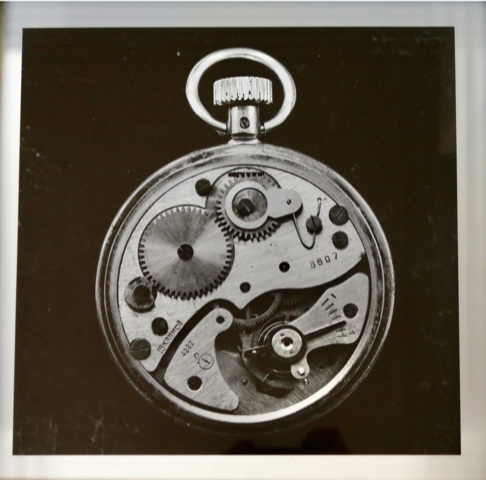

One of his photographic series, titled Síndrome del Impostor (Imposter Syndrome), offers a sly rendition of the Quixote theme that continues to pervade Latin American art. “In the Latin American imagination,” writes critic Reed Johnson, “Don Quixote has functioned both as a symbol of the former colonies’ knotty old-world heritage and as a rebel figure [who] pulls the rug out from under the Old World’s affectations.” Bordón photographed an array of highly crafted yet outdated mechanical devices — for instance, a Soviet-era chronometer — that no longer worked. In these images, as in Cervantes’s novel, idealism and disenchantment, brokenness and beauty, are inextricable.

In the streets of Havana, on every block, Spanish colonial opulence duels with weathered decay and picturesque disrepair. This amalgamation of pride and disappointment characterizes the attitude of many Cubans toward their beleaguered country. Grandiloquent patriotic signage dots the central highway. Aquí no se rinde nada (“Here we give up nothing”) reads one billboard, but for the watercolorist Henry Alomá, the truth is more complicated.

Alomá, a painter of whimsically surreal avian creatures and folk art themes, left Cuba in February 2020 for a one-month residency in Canada. The program stipend provided a small windfall for his family, but Covid intervened, and the lockdown stranded him thousands of miles from home for two agonizing years. For a time, he picked strawberries and asparagus on a Canadian farm; he sent money home through the Cuban embassy to sustain his wife and teenage daughter, but not all of it reached them. Returning home at last, Alomá found that his daughter, a talented singer with a possible recording contract in Spain, had been denied a Spanish visa because “she has the profile of a migrant.”

Alomá told us his story in his studio in the lush ecovillage of Las Terrazas. “I try to stay positive for my daughter,” he concluded, “but in truth I’m a broken man.” When we remarked that the art all around us was so bright and buoyant, he smiled and said, “I’m not broken when I’m painting. In my paintings, I’m whole.”