I relearned a valuable lesson about fishing this past weekend.

Hurricane Erin passed by us in a near miss. It’s worth mentioning that Erin did reach Category 5 on Aug. 16, which means the only thing that saved us from taking a major hit was the track of the storm. By the time most hurricanes that come this far north reach us they have been downgraded to tropical storm status, if that, with Hurricane Bob a notable exception to the rule. In Erin’s case, however, the storm was the real deal. But we were fortunate that a stationary weather front blocked Erin’s movement west, and the storm was pushed offshore enough to be a miss here.

But I digress. Back to the fishing lesson.

On Friday we had too much residual wind and too many big waves after Erin passed through to even think about venturing offshore. Whale watches and fishing trips were all canceled.

Saturday dawned with beautiful weather. But as I headed to the wharf to get the CeeJay ready for a trip, I found myself having a pity party over my coffee. Woe is me, I thought, after a whole day lost to the storm, now the water is going to be far too murky to catch fish. Woe is me, these unrelenting northeast winds Erin ushered in will have the water so chilled nothing will bite. Woe is me, the leftover swells from the storm are going to rock the fillings out of our teeth. The pity party lasted through my coffee, my ride into town, and my walk down the wharf to the boat.

Soon after we boarded 20 people, all very excited to go out fishing, I started my usual pre-trip speech: this is what we are fishing for, this is how we are fishing for them. But I peppered it with a warning that we were up against a stacked deck and then proceeded to list the reasons this trip had little chance of any real success.

Their faces fell. I wrapped up, hedging a little, telling them I would do my best to make lemonade out of lemons for them, and off I went up top to the bridge. A quick check of the water temperature at the dock showed a chilly 54 degrees and strengthened my belief that this trip was going to be an exercise in futility.

But off we go into the wild blue yonder.

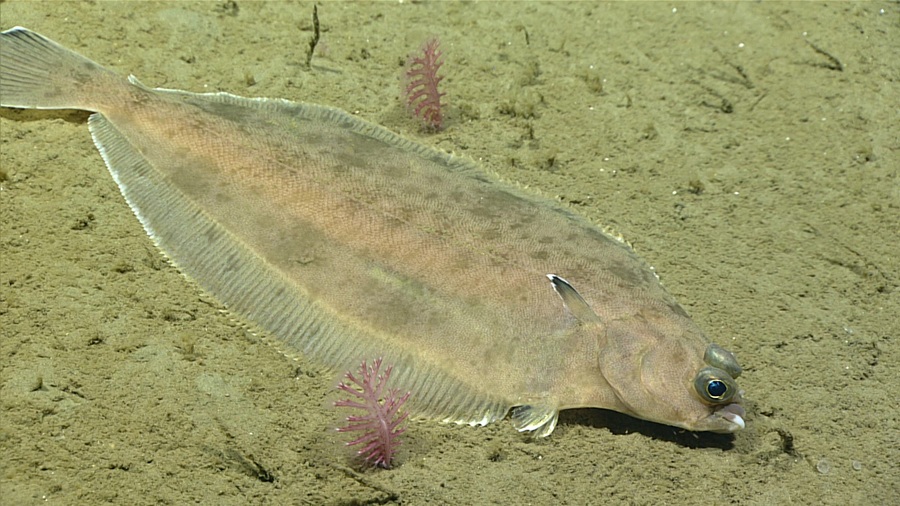

When I got to the Race, guess what? The water wasn’t as cold as I thought it would be. It was up to 60 degrees. The murkiness wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be, either. The waves weren’t too bad. The fish finder was showing massive numbers of bass in the water.

When you’re primed for the worst, it can be hard to believe things are looking up, even when they are. OK, OK, I thought. That’s all well and good, but I bet they won’t be biting.

A few minutes later, when the lines went into the water, we proceeded to have one of the best trips of the year. Many fish were fought and reeled in as the bite was on, and it was on strong. When all was said and done, 20 people brought in 20 keepers — our limit — and we threw back a dozen fish too big to keep. It was epic.

So, the lesson is that despite all the knowledge and wisdom I have acquired in 50 years of fishing, sometimes it’s best to simply go out there with no preconceived ideas about how it’s going to go. Sometimes it’s best to just shut up and fish.