Provincetown artist Laura Shabott, playwright Patrick Riviere, and the executive director of the Cape Cod Chamber Music Festival were relieved to learn that they had been selected for grants from the Arts Foundation of Cape Cod (AFCC) despite the abrupt termination of the foundation’s promised funding from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA).

With the support of the Cape Cod Foundation and anonymous donors, AFCC announced on June 26 that it would support the work of 18 arts organizations and 13 individuals. The grants will fund projects that the foundation hopes will “create access to the arts for all, breaking down barriers and fostering connection across Cape Cod.”

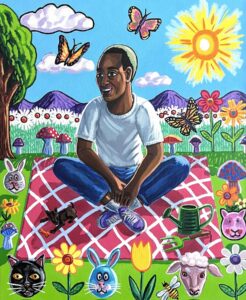

“To actually have the Cape Cod community rally and fund this grant was the real win for me,” said Shabott, recipient of a $2,500 grant. She plans to hire actors and other creatives for an October performance during her upcoming show at the Cape Cod Museum of Art. The piece will encompass theater and visual art and focus on an incident in 1941 when painter Lee Krasner met Tennessee Williams in the dunes.

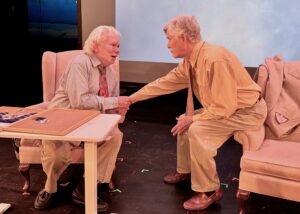

Riviere will use his $5,000 award to shoot a short film based on his play Remembering When I Used to Remember, about a gay Provincetown couple coping with one partner’s dementia. He plans to distribute the film for free to organizations supporting people with memory loss and their caregivers.

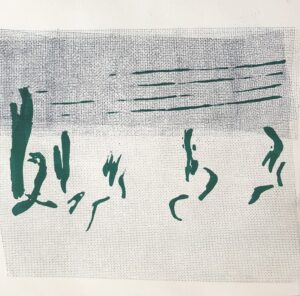

The Eastham-based Cape Cod Chamber Music Festival, recipient of a $1,500 grant from AFCC, will stage a free community concert in Hyannis. “In the past, we’ve had it at the Cape Cod National Seashore, but with their funding issues we realized there’s too much uncertainty and we needed to pivot to a new venue,” said Executive Director Andrea Meagher.

The awards are being made despite the collapse of what was supposed to be a local-federal funding partnership. The NEA had announced a $40,000 matching grant for the AFCC to fund Cape artists, but a May 2 email to the foundation said the award was being terminated because it failed to meet a new set of grantmaking criteria established by the Trump administration. New awards to artists and arts organizations would need to prioritize projects, the NEA told AFCC in the email, that “elevate the Nation’s HBCUs and Hispanic Serving Institutions, celebrate the 250th anniversary of American independence, foster AI competency, empower houses of worship to serve communities, assist with disaster recovery, foster skilled trade jobs, make America healthy again, support the military and veterans, support Tribal communities, make the District of Columbia safe and beautiful, and support the economic development of Asian American communities.”

While the loss of $40,000 doesn’t constitute a fiscal crisis for a foundation with an annual budget of just under $1 million, “it does come at a cost,” said AFCC Executive Director Julie Wake.

This year the AFCC awarded a total of $107,000 to artists and cultural organizations. Although it is the third year in a row that it has distributed more than $100,000, it represents a modest reduction from the past few years.

While acknowledging the challenges inherent in the new guidelines, Wake said her conversations with other arts leaders have led her to believe there will still be opportunities for federal support for the arts. She said their conversations have focused on five areas that would conceivably align with the new restrictions: the economic impact of the arts, educational outcomes, civic engagement, health and well-being, and heritage preservation.

Shabott also believes that artists should try to find ways to work within the new restrictions. “I would go for a grant knowing that I would not compromise my art,” she said. “I don’t like your guidelines, but I’m going to constrain myself to work within them in a very subversive way. And we can see examples of that throughout history.”

Riviere is more skeptical. “For me as an artist, if someone said to me, ‘Patrick can you Americanize or make this more patriotic?’ the answer would be no,” he said. “My play’s my play.”

FAWC Wins Appeal

At the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Executive Director Sharon Polli called the federal funding news “depressing.” For the most recent fiscal year, FAWC received 10 percent of its revenue from federal sources. While NEA grants totaling $50,000 have been withdrawn or terminated, FAWC successfully appealed the termination of a $50,000 grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

“This is very positive news for us, as it means that we can continue our scholarship efforts for our summer workshop program,” Polli said.

More positive news came last week from Beacon Hill, where the state legislature approved a budget of $61 billion that includes nearly $27 million for the Mass. Cultural Council (MCC), the state’s lead agency for funding arts organizations in local communities. Unless vetoed by the governor, which is considered unlikely, the appropriation will be the highest ever for MCC, just above fiscal 2025 funding levels.

Arts leaders are encouraged because it comes at a time when the state is losing millions in federal funds for education, health care, and environmental protection.

MCC is not completely dependent on federal funding (it received just over $1 million in fiscal 2025 from the NEA out of a $26 million budget,) but continued support from the state is critical for its survival.

“Without government money, we rely on private philanthropy, and that means that mostly the wealthy get to make decisions about how funds are distributed,” said MCC Executive Director Michael J. Bobbit. “Government money ensures that everyone has access to the arts in our state.”