In the third act of Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice, the stony guardians of hell’s gates instruct Orpheus, “You can’t sing here unless you sing in a dead language.” The libretto, which until that point had been in English, digresses briefly into Latin.

The moment is ironic, as the Metropolitan Opera has, historically, been a place for “dead languages” — traditional operas in foreign tongues by long-gone composers. But Eurydice, like Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, which also made its Met debut last month, aims to breathe some new life into the art form.

The libretto by Sarah Ruhl, based on her 2003 play, is colloquial, playful, and often funny. Aucoin’s music, dramatic but also not without humor, uses harp, marimba, and hand percussion in addition to the orchestra. It offers hints of Philip Glass, Carl Orff, and Stravinsky.

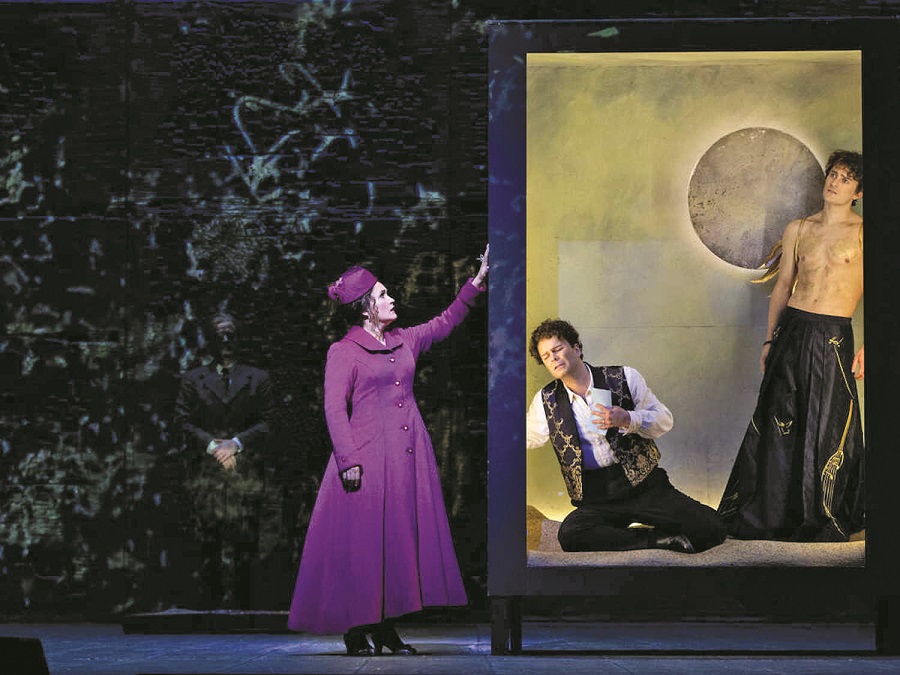

The first act opens with a beach scene, complete with colorful blow-up balls. Orpheus, sung by baritone Joshua Hopkins, proposes to Eurydice, sung by soprano Erin Morley, by winding a piece of string around her finger. Orpheus’s double, sung by countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński, is lowered from the sky in a beach chair. They duet for the rest of the opera, except when Orpheus descends into the underworld alone.

Musically, it’s very effective. Orliński’s crystalline voice casts a halo above Hopkins’s, forming dissonant intervals at tense moments. But narratively, it’s confusing. It is unclear exactly what the slightly androgynous double is supposed to signify. Orpheus’s divine half? A stand-in for his lyre? And if the opera is supposed to be about the myth’s female protagonist, why are there two of Orpheus?

Eurydice, bored by her wedding celebration — which includes dancers flossing, presumably a first on the Met’s stage — meets a disguised Hades, sung brilliantly by tenor Barry Banks, at the water cooler. Socially awkward and Beetlejuice-like, Hades lures Eurydice to his apartment by claiming to have a letter from her deceased father. Aucoin’s use of marimba here evokes skeletons, as Banks sings in his strained upper range. Eurydice falls down a flight of stairs to her death.

The first act transitions seamlessly into the second. The minimalist set is put to good use, with surreal lighting and a trap door. In the underworld, we meet a trio of characters who could have come out of a Disney movie. “We are a chorus of stones,” they sing. “I’m a big, I’m a little, I’m a loud stone. Here are some of the dead.” They gesture to a cluster of moaning heaps. “Shut up! We are telling a story.” Eurydice arrives in a raining elevator, a modern update on the River of Lethe.

Though Eurydice has lost her memory, she is able to relearn language when Orpheus, like someone sneaking cigarettes into prison, lowers the collected works of Shakespeare into the underworld. The director’s decision to project the libretto onstage, distracting until that point, suddenly makes some sense.

Eurydice meets her father, a character missing from the original myth and based on Ruhl’s own father. This oddly paternalistic choice somewhat undermines the libretto’s supposed feminist bent. Orpheus, wallowing in grief, decides that he will save Eurydice from the underworld. “This is what it is to love an artist,” she sings.

The third act goes on for too long. When Hades asks Orpheus, “Are you certain which you’d choose?” referring to music or Eurydice, the dichotomy feels forced. It would make sense for the opera to end when Eurydice, following Orpheus, startles him by calling out his name. They meet eye-to-eye for a moment before Eurydice is plunged back into hell.

Instead, the story loses momentum. Eurydice writes in a letter to Orpheus that she does not know why she called out to him. This is a missed opportunity for character development — did Eurydice perhaps not want to leave her father? The opera ends with a tragedy of errors reminiscent of Romeo and Juliet — first the father, then Eurydice, then Orpheus erase their memories. The audience, too, is left a little confused.

Despite the libretto’s shortcomings, the music for Eurydice is consistently delightful. The opera is, ultimately, a meta-commentary about the genre. Opera is the union of music, represented by Orpheus and, by extension, Aucoin, and language, represented by Eurydice, or Ruhl. I suspect Aucoin will have more to say about this in his book, The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera, forthcoming in December.

To Hell and Back Again

The event: Eurydice live in HD

The time: Saturday, Dec. 4, 12:55 p.m.

The place: Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater, 2357 Route 6

The cost: $15 to $30 at what.org