Over decades of artmaking, Ellen LeBow has forged her own path through stages and styles, figurative rather than abstract. The luminous scratchboard drawings she shows at Rice Polak Gallery in Provincetown reveal her fascination with the stories of humanity and of the divine.

With her newest bas-relief work, however, inspiration and intuition take precedence over narrative.

LeBow’s tastes, reflected in artworks that fill her two-room studio-living space in Cambridge, are devoted to cross-cultural rituals and belief systems imbued with personal meaning. There’s a picture of a saint on her strawberry-red refrigerator; a large floral painted on a screen that came from a Christmas Tree Shop and that now serves as a curtain for her wardrobe; a milagro, a metal representation of a leg she brought back from Italy.

In the same way that people once gathered and prayed with milagros for the healing of various body parts, LeBow says, “I gather things that are powerful for me or inspiring to me.” These talismans often appear in her work.

Alongside the milagros, on a stand in front of a mirror surrounded by small sparkling lights is a baby Jesus doll from Mexico tricked out as a doctor. “It is believed that Doctor Jesus will heal you,” LeBow says. “I always talk to him before I make new artwork.”

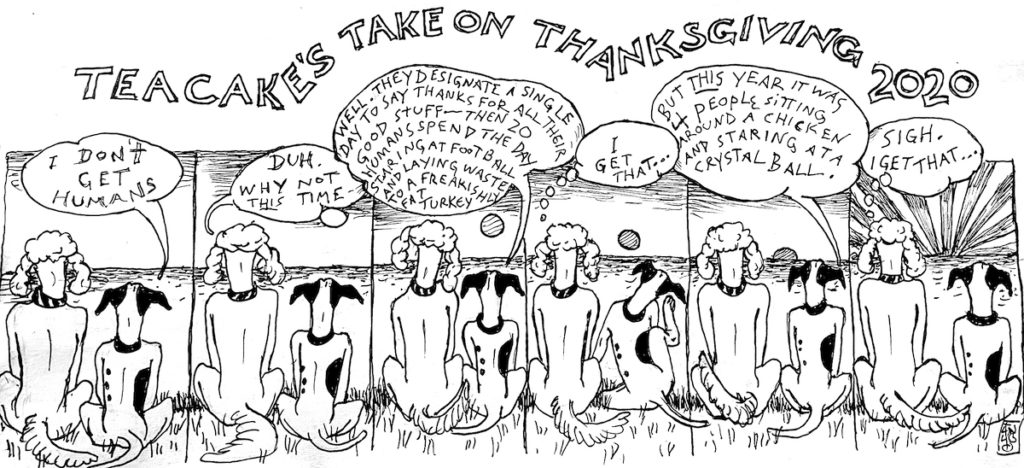

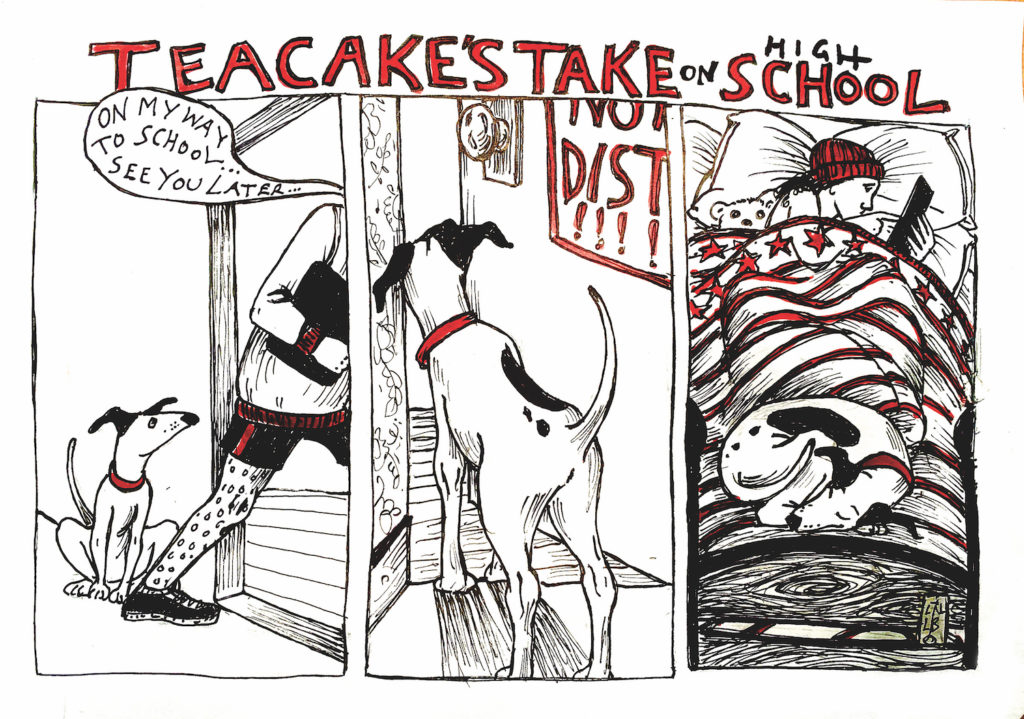

In the late 1970s when she was finding her voice in Wellfleet and making clay whistles modeled on pre-Columbian spirit vessels, Lebow saturated them with her own feisty energy and humor. This writer purchased two of them back then: a goddess figure whose whistle is behind her head, which was crowned with a moon-shape, and a seated indigenous figure that whistles when you blow into one of her breasts.

The pre-Columbians made these whistles with the idea that when you blow into them you hear the spirit’s voice, LeBow says. But hers are inspired by Aztec gods and are not meant to be anything but themselves.

“I’ve always been interested in other cultures’ artworks more than contemporary American art,” says LeBow.

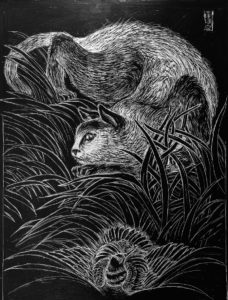

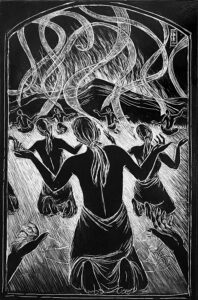

The scholarly, inventive, well-traveled LeBow has been showing at Rice Polak since it opened more than three decades ago. She is best known for ink drawings of Haiti rendered on clayboard — a type of scratchboard. These are created by carving into a black surface to reveal white lines beneath.

“I begin with a white surface and brush India ink onto certain areas of the board to create the base of a composition,” LeBow says. On many of them, she then goes on to etch the stories of struggling, determined people, including those she spent years working with in Haiti, and gestures and symbols that allude to faith and survival.

LeBow is fascinated by symbolic forms. In 2018, when the Provincetown Community Compact’s annual Swim for Life marked its 25th year, LeBow was tapped to create the event’s design. She drew a Tree of Life, an archetype in many mythological traditions. In LeBow’s rendering, a green tree, festooned with blossoms and fruit, is set in an orange lifeboat, heralded by a swimmer blowing into a bright orange horn as she heads across Provincetown Harbor.

To LeBow, the Tree of Life also celebrated the survival of Art Matènwa, a collaborative arts center on the island of La Gonâve in Haiti in which she and other Outer Cape artists had become deeply involved. Art Matènwa evolved into a gathering place where women created items — mostly silk scarves — that LeBow sold in RaRa, a Wellfleet shop that sent profits back to the collaborative in Haiti.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into,” she says of her connection with Haiti, which began 25 years ago. “It changed my life.”

LeBow began a different sort of odyssey in 2020. Traveling through Mexico, she studied ancient bas-relief sculpture. When she returned, she moved from making ink drawings on clayboard to teaching herself sculptural techniques. In bas-relief, she found a dramatic difference in the way an image appears from the background. Rather than being scratched from a darkened board, her subjects now rise from the background surface.

Unlike Egyptian marble or stone bas-reliefs, sculpted to achieve a smooth, polished surface, LeBow’s work is looser and rougher in spots, dynamic rather than tranquil. Since LeBow works with white clays, cements, and papers, her bas-relief sculptures depend on light and shadow to be revealed. “If the light is too bright,” she says, “you can’t see the form.”

A long-necked cat adorns many of LeBow’s bas-reliefs. Before setting out for Mexico, LeBow had become fascinated by Bastet, an ancient Egyptian divinity, half human and half cat with a long and stylized neck, whose powers of protection and pleasure can be both benevolent and sinister. “Bastet is the idea, the archetype, of a cat,” she says of the goddess.

After translating Bastet using malleable materials, LeBow turned to Sekhmet, also a cat, but this one depicted as a lion-headed woman, or a lioness — Bastet’s warrior aspect. Sekhmet’s image inspires certain features of LeBow’s new sculptures: sharp teeth, claws, and a battle-ready stance. An element of ferocity runs through LeBow’s new work.

The Book of Imaginary Beings is one of LeBow’s favorites. In it, Jorge Luis Borges refers to medieval monks’ fascination with creatures in Greek mythology, including hybrids. And hours spent in the Wellfleet Public Library poring over Christian Heck’s The Grand Medieval Bestiary led her to more figures that are half human and half animal, “like a hyena that could be both male and female, and had a star in the middle of its eye,” LeBow says.

Around her neck LeBow wears a circular Sekhmet amulet. The cat’s profile, crowned with a shape symbolizing the Sun, is modeled on an Egyptian representation of the goddess.

“I’ve worked in all kinds of mediums over the years,” says LeBow. “To move from techniques I knew well is very rejuvenating. The bas-relief pieces are like beginning again.”

Imaginative Mythologies

The event: Bas-relief sculptures by Ellen LeBow

The time: Through Wednesday, Aug. 28; opening reception Aug. 16, 6 p.m.

The place: Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: Free

Editor’s note: Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this article, publish in print on Aug. 15, incorrectly credited the photo of Ellen LeBow to Agata Storer. The portrait was taken by Edward Boches.