“We believe we make our choices, but no — they make us,” writes the late Daniel Menaker in his poem, “Last Will and Testament.” Though our choices add up to more than the sum of our parts, such a realization may feel incomplete, because we are also made of parts we do not choose, such as sexual orientation, illness, and skin color. These can create tremendous inner turmoil. In newly released memoirs, the exceptionally gifted graphic novelists Eleanor Crewes and Allie Brosh explore their sometimes comedic, sometimes excruciating struggles to be in the world as their true selves.

Crewes and Brosh each started by creating an autobiography with relatively slender aims.

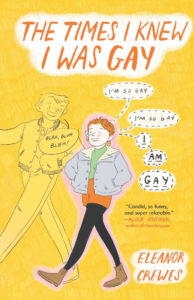

Crewes began The Times I Knew I Was Gay as a 10-page zine, which she delivered to comic shops throughout the U.K. “It quite quickly turned into a tale that I knew was much bigger than something I could fit into those hand-stitched comics,” she writes. She wasn’t creating a “handbook for coming out.” Instead, she wanted to show what it was like to be herself and gay. The book, published in Britain in 2018, has now been released in the U.S.

Brosh’s version of a zine was a blog, begun in 2009. Surprised by its popularity, she expanded it into book form. Hyperbole and a Half was published in 2013, and Solutions and Other Problems, in September.

Both Crewes and Brosh are particularly good at combining words and images to explore conflicts born of self-awareness. Crewes, for example, draws herself at the height of her denial, when she is headed for university, with long, flowing hair and a pierced nose, wearing sexualized, feminine clothing. “I lived my life in shadow,” she reflects. “Never the sun on my face.”

Over a two-page spread, Crewes demonstrates the many iterations of being in the closet. From left to right, there’s a “clothes rail,” a closet with doors entirely shut, and a large closet with an image of herself seated inside, doors wiiide open. “People might think that everyone starts out in a closet until they’re ready to ‘come out,’ ” Crewes writes. “But what’s funny for me is that I didn’t even know that there was a closet — or that I was very much stuck inside it.”

Brosh is conflicted and closeted, but not about being gay. She describes herself as a “weirdo.” The avatar she has drawn of herself is a bright pink cylinder topped with a bean-shaped head, sprouting a yellow, fin-like ponytail. She manages to express everything from determination to despair through the character’s mouth, eyes, and posture. Her ingenuity is in combining such simple drawings with complex writing.

The three-year-old version of Brosh, for example, finds herself in nearly inexplicable predicaments, from repeatedly getting stuck in a bucket to stealing her neighbor’s belongings. Though the neighbor is unaware, “The connection should have been obvious,” Brosh writes. “But, when faced with a mystery like, ‘Where did my remote control go? Why is there a piece of paper with a child’s handwriting on it hiding in the VCR? And how do these rocks keep getting in here?’ almost no rational adult would jump to the conclusion ‘because a child has been sneaking in through my cat door and leaving these for me to discover.’ ”

Pain exists just below the surface. In the years preceding Solutions and Other Problems, Brosh suffered a baffling illness requiring invasive surgery, lost her younger sister to suicide, experienced her parents’ divorce, and dissolved her own marriage. Severe clinical depression ensued. In a chapter titled “Losing,” she shows her little pink avatar dancing, enjoying the hell out of her weirdo moves. As depression takes hold, the dancing ceases, and images of a crazed tornado tear across the page.

“Unfortunately, the world doesn’t make sense,” Brosh declares. “And once you start to notice this, it rips through you like a Tasmanian tornado octopus, rending your stupid little sense of meaning apart with its flailing power arms.”

How can any of us be happy under such circumstances? Crewes and Brosh offer hope. Crewes draws images of her external transformation, which she links to internal shifts. She shows herself cutting her hair, trying on comfortable clothing without imagining what a boy will think, and beginning, at last, to date women. It takes her several tries to experience actual attraction — a like-minded friendship ignites a spark.

Her description of their first kiss is made all the sweeter by illustrations. “I smiled the whole way home that night,” she writes. Panels accompanying this sentence show herself smiling as she takes off her shoes, brushes her teeth, and lies down in bed. This last drawing has a one-word utterance: “Wow.”

Brosh offers less of a step-by-step chronicle of her shift to self-acceptance, and the pieces sometimes feel too tenuous to hang together as a whole. But she gets there, and the payoff for readers is sizable. In chapter 17, “Loving-Kindness Exercise,” the little pink creature tries an online meditation class, her impulsive A.D.D. mind zooming hither and yon. At chapter’s end, over panels in which she pokes through random objects — musical instruments, a bowling ball, a banana — Brosh sets out her own life rules: “How to Act Like a Fuckin’ Weirdo / do not know what you are doing / try harder / do not ever give up.”

Eight chapters later, in “Friend,” the book’s last section, she depicts two selves, one in red, the other in a pale yellow. She admits to loneliness. “I felt pretty offended by it,” she writes, “I mean what am I — some clueless animal who needs love and companionship? As it turns out, yes.” What follows are some of the loveliest, most poignant attempts to render in words and images what it’s like to befriend oneself. Brosh laces up sneakers and goes for a run — with herself. “Because,” she writes, “nobody should have to feel like a pointless weirdo alone. Especially if they are.”

Crewes and Brosh make choices for themselves and the kinds of lives they want, for sure. Most important, they choose to peer deep inside themselves, paying attention even to the things they find most objectionable. Ultimately, they choose to befriend themselves. It’s as close as any of us is likely to get to anything remotely resembling happiness.