I have an image flaming in my head, and it’s glorious. Edward Gorey (or Ogred Weary, for he often used anagrams) drives up to his house in Yarmouth Port. He has just arrived from New York City after the opening of Dracula on Broadway in 1977.

The door of his yellow VW Bug opens with a creak, and Gorey unfolds his long frame onto Strawberry Lane. The hem of his fur coat falls to his ankles like a curtain. His old sneakers are scuffed and worn. What would become known as the “Elephant House” stands somewhat strangled by vines and overgrowth. Then he begins to unload three large, ornate bird cages from the back seat of the car. They serve as pet carriers for his six beloved cats.

This is how docent Mary Ann Albertine begins our tour of Gorey’s home, apocryphal as the story may be. She is well aware that her own adoration of Gorey’s work may have distanced her from any pesky facts that might get in the way of a good story (Gorey bought the house in 1979).

“He would have hated me,” she says. “He was a very private man. He did not like fans. But he did have hundreds of friends.”

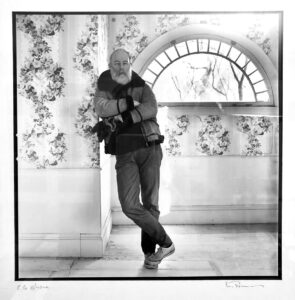

This tension between fame and reclusiveness was an essential part of the author, illustrator, playwright, costume designer, and set designer’s identity. He once told an interviewer upon being introduced, “I have nothing to say,” then went on to regale him for hours with rich stories about the composition of his books.

The Edward Gorey House, now a museum, is meticulously maintained, but it was not always thus. Gorey designed the sets and costumes for the wildly successful Dracula production, and his payday allowed him to buy the dilapidated 200-year-old captain’s house and make it habitable.

When Gorey died in 2000 at age 75, the house contained 25,000 books — and that’s just the books. Gorey was an inveterate collector, and every room was stuffed with things that he found delectable and destined to become art. There are seven or eight doors in the house that lead to the outside, but Gorey apparently used only one that opened into the dining room. Here, Gorey would place every piece of “art” that he had brought home on every available surface, table, chair, or floor to await further classification.

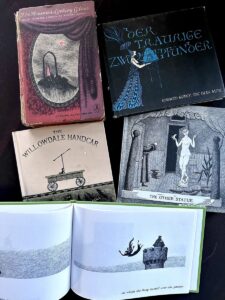

Kevin McDermott’s 2003 book of photographs, Elephant House: or, the Home of Edward Gorey, captures the house shortly after his death. According to McDermott, it was given the name because of “the size of the house, or the exterior wooden shingles, which for many years were gray and crackled like elephant skin.”

The bright airy rooms of the Elephant House, which now display his transformed gems, also show the breadth of Gorey’s creative work and give you a feeling that you are standing with a true genius, a human being for whom words often were insufficient, who was forever pondering, as docent Albertine says, “the question of what reality could be.”

The small display of his intricate designs for Dracula plays on the imagination. A daydream begins. You are sitting in the opera loge craning your neck to take in this massive, elaborate set. In fact, when the curtain rose on the opening night of Dracula, the audience burst into loud applause even before the actors came onstage. The set received an ovation.

After Gorey bought the house, carpenters worked on it for two years before he set foot inside. Apparently, for all his terseness and eccentricities, everyone loved Gorey, even the contractors who resurrected the Elephant House. Without prompting, they fashioned the brackets holding up the fireplace mantel to look like bats. And when they told him that raccoons were in the attic, Gorey replied, “Well, I suppose they’ve been there well before I arrived, so let them stay.” They did.

Passing by the life-size mannequin displaying one of Gorey’s famous floor-length coats (this one of raccoon fur), you enter the “ballroom.” There has never been any dancing in the ballroom. Here you get the full feeling of Gorey’s playfulness. When he was alive, this room was filled with balls — every manner of orb that Gorey could lay his hands on: stone, marble, rubber.

The Elephant House was one part of a repeating triptych in Gorey’s life. Every day, he ate at a local restaurant, Jack’s Outback, no doubt listening to Jack as he meted out his insults. Gorey reportedly stuffed extra money into the till to intentionally unbalance Jack’s bookkeeping.

After breakfast, Gorey visited Parnassus Books to bolster his library. “Oh yes, Mr. Gorey was a great friend of the owner here,” the proprietor told me. “He used to come in often, sit on the floor, and sort books.” Ever the prospector mining for a gem.

McDermott visited the house in the weeks after Gorey’s death and faithfully preserved in photographs the chaotic and wonderful details of the artist’s life. I found this book to be an invaluable part of the record, for it would have been impossible to preserve the house as it was when he lived in it. Looking at the mass and jumble of these photos, one might begin to think of Gorey as a man living in a mine surrounded by ore. And he did indeed have the look of a prospector, one who had the vision to see the gold, the diamond, the spectacular hidden within the everyday.

The Gorey House at 8 Strawberry Lane in Yarmouth Port is open most days, April 4 to Dec. 29. See edwardgoreyhouse.org for an exact schedule.