What is known about Edith Lake Wilkinson: she was a woman, a visual artist, a painter, printer, and draftsman; she was a pioneer of white-line printing; she lived in New York City but fell in love with Provincetown; she was gay and had a long-term female lover; she was ultimately institutionalized by a family lawyer who proceeded to siphon funds from her inheritance.

What Jane Anderson, Wilkinson’s great-niece, wishes she knew: What drew Wilkinson to Provincetown? Was she the very first artist to create a white-line print and, if so, why isn’t she recognized for it? What was it like growing up as a gay woman in the early 1900s?

Why was Wilkinson sent to a psychiatric hospital? Did she really need to be?

Anderson’s curiosity about her great-aunt began in childhood. She grew up surrounded by Wilkinson’s art after her mother brought home hundreds of Wilkinson’s paintings that she found packed away in trunks in a relative’s home.

In her 2014 documentary Packed in a Trunk: The Lost Art of Edith Lake Wilkinson, Anderson documents her quest to find answers about her great-aunt — the astonishing life this woman led, and the abrupt conclusion to that life. “It’s time to give Edith’s story a better ending,” Anderson says at the film’s beginning.

Wilkinson grew up in Wheeling, W. Va. but moved to New York City in 1888 at age 19 to attend the Arts Students League. She thrived in New York and went on to earn a degree at Columbia Teachers College, “where she was exposed to the advanced art theories of the day,” Anderson says.

In New York, Wilkinson met a woman named Fanny Wilkinson (having the same last name was a happy coincidence) and “something clicked between them,” Anderson says. They became lovers, moved in together on the Upper West Side, and traveled several times to Europe, where Wilkinson learned from prominent artists.

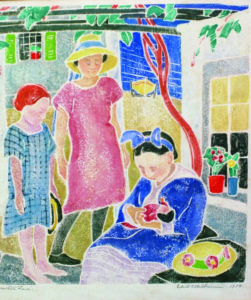

“Edith filled canvases and sketchbooks with her impressions of the European landscape,” Anderson says. She also sketched Fanny many times — mostly in peaceful domestic settings.

In 1914, Wilkinson spent the summer in Provincetown, where “her canvases took on a whole new light,” Anderson says. White-line printing, also known as the “Provincetown Print” and based on Japanese woodblock printing, is said to have been invented by Bror Julius Olsson Nordfeldt in 1915. But Anderson possesses a white-line print of Wilkinson’s dated 1914, suggesting that Wilkinson may have pioneered the technique.

“She was doing this before everybody else was doing this, yet she didn’t get the credit like everybody else,” says Christine McCarthy, CEO of the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

Wilkinson returned to Provincetown summer after summer. As the years went by, her work evolved. “When she first got to Provincetown, the palette was in pastels, soft colors, drenched with sun,” Anderson says. Eventually, Wilkinson’s work shifted from the light colors of impressionist work to the deeper, brighter tones and looser shapes of fauvism.

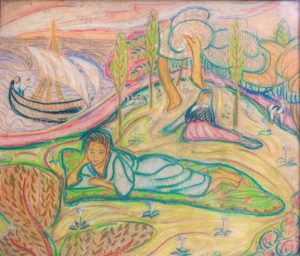

One pastel drawing has a particularly mystical feel. The soft pinks, greens, and blues contribute to a fairytale-like landscape, and each figure, plant, and cloud is drawn with soft, smooth lines — there are no hard edges or corners. The curved tree trunks and swirly leaf and cloud shapes evoke a swaying sensation.

Wilkinson’s art, according to McCarthy, is purposefully vague. For example, figures’ facial features are often obscured in shadow, concealing their expressions and emotions. “She allows you to create your own narrative when you look at these pieces,” McCarthy says.

Despite the lack of facial expressions in many pieces, “There’s still a sensuousness, a humanity to it,” Anderson says. “It’s not just an intellectual study.”

In 1924, Wilkinson was admitted to Sheppard Pratt, a private psychiatric hospital outside Baltimore, with a diagnosis of “paranoid state.” George Rogers, a family attorney, signed her in. She was transferred in 1935 to Huntington State Hospital in West Virginia, where “she suffered extreme neglect,” Anderson says. At the same time, Rogers continuously siphoned funds from Wilkinson’s family inheritance. Wilkinson died in 1957, having spent the last 32 years of her life in a mental hospital.

“Edith toppled into obscurity because of what happened to her,” Anderson says.

Like Wilkinson, Anderson is a gay woman and heartbroken that Wilkinson was separated from her partner when she was sent to Sheppard Pratt. “I have the life that Edith should have had,” Anderson says. “I have always felt that I owed it to Edith — who taught me how to see the world — to get her work back out there.” She has succeeded: Wilkinson’s art is being shown at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum now through Aug. 21.

The last painting Anderson recovered — quite possibly Wilkinson’s final work — is of Provincetown. It’s dated 1925, and since Wilkinson was at Sheppard Pratt by then, she must have painted it from memory, Anderson says.

Why was Provincetown her final painting? Anderson thinks she knows: when things were falling apart in Wilkinson’s life, “she needed Provincetown to be with her.”

Hidden History

The event: An exhibition of paintings by Edith Lake Wilkinson

The time: Through Aug. 21

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: Free