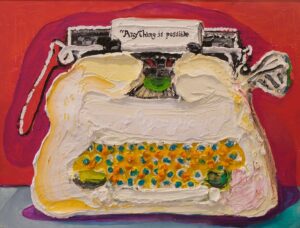

“Anything is possible” is written at the top of a painting by Sam Messer currently on view in “Edge Conditions,” a group exhibition of work by former visual arts fellows at the Fine Arts Work Center. The phrase appears on a sheet of paper arising from a typewriter. In an exhibition that features representational art, the phrase challenges the viewer to reconsider the visual possibilities inherent in artwork that claims to depict real things, such as the typewriter in Messer’s painting or the two figures sitting listlessly on a dock in a painting by Matt Bollinger, the show’s curator.

The show’s title is a term in urban design that describes the junction where contrasting elements meet. Bollinger relates the concept to his experience of walking from a parking lot to a dune shack and traversing asphalt, sand, and several distinct ecosystems.

“The works in this exhibition exist in edge conditions, junctions of contrasting elements, ideas, materials, and images,” he writes. “Some draw attention to the contrast between elements, leaving their seams visible… Others hide their joints under the illusion of continuity.”

In Messer’s painting, the typewriter sits on a desk and dominates the composition in the manner of a portrait. Ostensibly, this is a painting of a typewriter. But Messer’s painting, like many similar ones he has painted, is not really about the typewriter. Rather, the object becomes an armature to explore the material possibilities of paint.

In Anything Is Possible, Messer renders the white body of the typewriter by slathering butter-colored paint onto the canvas with the decadent flourish of a baker icing a cake. For its keys, he squirts out dollops of paint straight from the tube. They lie on a surface that looks like an orange fish skin, created with an oily varnish. It’s fun to observe how he renders the delicate mechanical innards of the typewriter with his heavy-handed touch.

In his exhibition statement, Bollinger writes about how the parts of each painting become more than their sum. In Messer’s case, the painterly components of the work far outstrip any interest in the typewriter as an object.

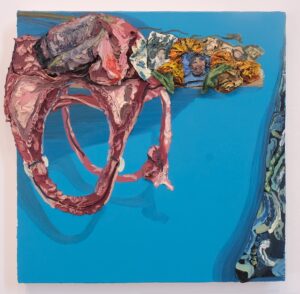

Herman Aguirre pushes the material possibilities of paint even further in a pair of meaty paintings in which he builds three-dimensional forms with globs of oil paint and oil skins. It’s unclear what these amorphous forms are supposed to represent. But there are discernable images in their midst, like flowers and a portrait, and the shadows they cast render them as physical objects, not just abstract forms on a canvas.

As in Messer’s paintings, representation takes second place to material play in Ezra Johnson’s depictions of stacks of sketchbooks. While Johnson works with much thinner paint, his loose gestures and casual approach to drawing locate these paintings in a territory that straddles both geometric abstraction and representation.

Johnson’s concern with abstraction extends to his use of color, where he juxtaposes a primarily blue palette with sparse reds. Circular marks denoting the edge of a spiral-bound notebook, along with a children’s drawing on one surface, shift the image back to representation. But as viewers, we’re left on unstable ground, always oscillating between understanding the work as abstract one moment and realistic the next.

For the artists in the show who work more solidly within the camp of representation, the edge conditions — or fissures between reality and artifice — are revealed through close looking. From a distance, works by Ellen Akimoto and Phil Whitman appear as legible pictures of everyday scenes.

Akimoto paints from a perspective of looking down at a houseplant. What appears as a photographic likeness of the serpentine plant unravels when one notices the ghost of a form in the background of the painting. Is it another leaf or a discarded idea? Likewise, the pot is only legible through its shape and shadow. Its surface is unrendered; it’s a wash of paint, a notation of color. Here, painting offers an opportunity to experience the passage of time and the process of something coming into being.

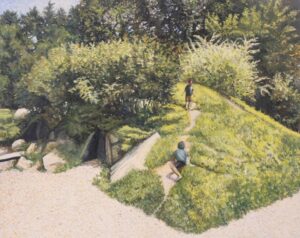

Whitman paints what appear to be commonplace scenes of a red barn and children playing in a park. In Noli Me Tangere: Kensington Playground, he works with egg tempera on panel to capture the variety of color and texture in the scene. His fastidious, obsessive marks render the space with a hyperrealism that far surpasses casual observation. The marks create a reality unto themselves, dancing across the surface of the panel in all manner of movement. They sway and overlap each other in a grassy hillside; when depicting gravel, they’re measured and uniform. The picture recalls the strangeness of looking at something too closely or under a microscope.

In his other painting in the show, Cerridwen, Whitman pays close attention to overlooked details like vines growing out of a gutter and the variation in color among shingles on the roof of a barn. Two abstract forms hang on the barn doors. They could be images, like Midwestern barn quilts, attached to the surface of the doors. But they could just as likely be abstract aberrations from the artist’s imagination.

The slipperiness of realism surfaces in many of the other works in the exhibition, including James Stanley’s tender portrait of his daughter. The tight rendering of her face and strands of hair gives way to a background painted in lush swirls of purple paint. Anne Clare Rogers’s sculpture Weathervane depicts a leg made of paper and human hair. The hairs protrude from the surface of the sculpture with a creepy, lifelike accuracy. But the illusion falls apart upon close inspection: what appears as skin is paper, and the leg tapers off before a foot is rendered. There’s more at play here than mere illusionism.

Whereas realism can often be perceived as stodgy or academic, reality becomes a fertile territory for creative possibility in “Edge Conditions.” In the process, the show reorients us to our reality, making us see the world anew — or, at least, through the eyes of someone else.

Bollinger’s painting of two figures smoking and drinking Slurpees by a lake could easily have been a banal and unglamorous image of suburban ennui. But he elevates the scene through a dramatic, almost ecstatic use of color. “Anything is possible” guides Bollinger’s formal decisions, adding a spark of magic to the mundane.

‘Edge Conditions’

The event: An exhibition of work by former fellows of the Fine Arts Work Center

The time: Through Aug. 23 in Provincetown; Sept. 6-8 in New York City

The place: Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown; The Armory Show, 429 11th Ave., New York City

The cost: Free (Provincetown); $57 (Armory Show general admission)